FOREWORD: As many of you know, I have been working for some time on a book dealing with creation in Scripture. I am planning to finish that book in December, and to see it in print next year. Many of you have been praying for this project, and through your questions, comments, and discussion in classes and retreats have helped shaped my thinking. Thank you! This is a bit of my work in progress, dealing with the translation of the Bible’s first words.

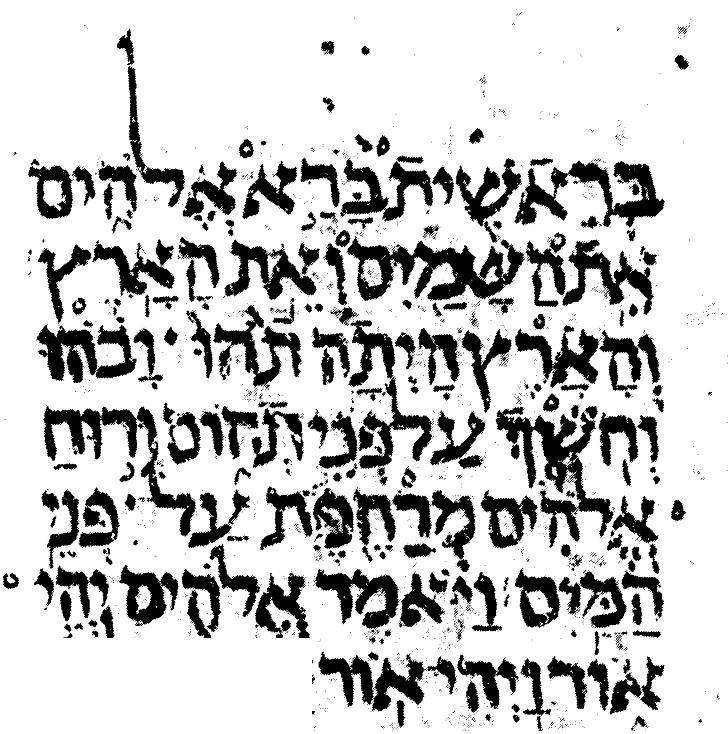

Translation questions emerge with the very first word of the first creation story in Scripture. We are accustomed to reading Genesis 1:1 as a sentence, introducing the account that follows: “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth” (Gen 1:1 KJV, RSV, NIV, ESV). But in many recent translations, this verse is rendered not as a sentence, but as a dependent temporal clause: “When God began to create heaven and earth—the earth being unformed and void” (Gen 1:1-2 NJPS; compare NRSVue and CEB).

At issue is the first word in the MT, bereshit: reshit, “beginning,” with the prefixed preposition b, typically “in” or “with.” The problem is the absence of the article: as any beginning Hebrew student knows, were this word to be read unambiguously as “in the beginning,” it would be vocalized as bareshit. Without the article, the b should be read as “when” rather than “in,” making Gen 1:1 a clause providing “the temporal setting for the description of pre-creation elements in Gen 1:2” (David M. Carr, Genesis 1—11, International Exegetical Commentary of the Old Testament [Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2021], 47). It is true that Hebrew sometimes omits the article, particularly in poetry, so either translation is possible. But this unit is not poetry, and nowhere else in this first chapter has the article been omitted. With medieval Jewish commentators Rashi and ibn Ezra, we should render this first verse “When God began to create the heavens and the earth. . .”.

Robert Jensen decries this shift in translation on theological grounds:

On the other hand, if we follow the creed’s unmitigated confession of God the Creator, we will read, ‘In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.’ Therewith we will do an intellectually and spiritually tremendous thing, for there can hardly be a proposition more upsetting to our inherited metaphysical assumptions . . . Christianity’s doctrine of creation presents a drastically revisionary metaphysics, a construal of reality that affirms an encompassing creaturely contingency: we and all our universe might not have been (Canon and Creed. Interpretation: Resources for the Use of Scripture in the Church [Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2010], 91).

Surely, whether we translate Gen 1:1 as an independent sentence or a temporal clause, the radical contingency of the world is the point of this first creation account—apart from God’s sovereign creative will and word, our ordered world would not be. But while creatio ex nihilo (“creation out of nothing”) is an important theological claim, to Muslims and Jews as well as to Christians, that is not what Genesis 1:1—2:4a is about. Quite apart from grammatical concerns, if our aim is to preserve creatio ex nihilo, translating Genesis 1:1 as a sentence is no real help. Genesis 1:2, with its description of uncreated watery chaos, already defeats that purpose, as the rabbis long ago realized. In Midrash Bereshit Rabbah 1:5, R. Huna says, “If it were not written, it would be impossible to say it. ‘In the beginning God created’ from what? ‘And the earth was empty [Hebrew tohu wabohu].’” Creation begins with chaos.

The question posed by the beginning of the Bible is not, after all, “How, or from what, did God create the world?” Ancient people likely did not worry much about such abstract questions. What they wanted, and needed, to know was more immediate and pressing: Will the sun rise again in the morning? Will the winter pass, and the spring come again? In short: is there a meaningful order to reality? The first creation account affirms that the world does make sense. God has established order, not chaos.

The expression tohu wabohu (“formless void” in the NRSV) presents translation challenges of its own. The first term, tohu, occurs twenty times in Scripture, just over half of these in Isaiah alone (eleven times: Isa 24:10; 29:21; 34:11; 40:17, 23; 41:29; 44:9; 45:18-19; 49:4; 59:4). As used in these Old Testament contexts, tohu appears broadly to mean emptiness or nothingness: whether an empty, and so worthless, action (“I have spent my strength for nothing [Hebrew letohu], and vanity,” Isa 49:4 NRSV; cf. Isa 29:21; 40:7, 23); empty, vain idols (“Don’t turn aside to follow useless idols [Hebrew hattohu] that can’t help you or save you. They’re absolutely useless [Hebrew tohu]!,” 1 Sam 12:21 CEB; cf. Isa 41:29; 44:9); or an empty land (“God found Israel in a wild land—in a howling desert wasteland [Hebrew betohu],” Deut 32:10; cf. Ps 107:40; Job 6:18; 12:24). Apart from Gen 1:2, tohu is used three times in a context that refers to creation: Job 26:7; Isa 45:18-19, and Jer 4:23. Job 26:7 says of the Almighty, “He stretched the North [Hebrew Zaphon; evidently, God’s dwelling place; cf. Ps 48:1-2] over chaos [Hebrew tohu], hung earth over nothing.” From the anonymous prophet of the Babylonian exile called Second Isaiah, Isaiah 45:18-19 appears to relate not only to creation, but specifically to Genesis 1:

For this is what the Lord said, who created the heavens,

who is God,

who formed the earth and made it,

who established it,

who didn’t create it a wasteland [Hebrew tohu] but formed it as a habitation:

I, the Lord, and none other!

I didn’t speak in secret

or in some land of darkness;

I didn’t say to the offspring of Jacob,

“Seek me in chaos [Hebrew tohu].”

I am the Lord, the one who speaks truth,

who announces what is correct (Isaiah 45:18-19 CEB).

Not only do the word tohu and God’s creation of the heavens and the earth (cf. Gen 1:1) connect these passages, but also the verb translated “create” in Isa 45:18 is bara’, the same verb used in Gen 1:1, 21; 2:3-4a. Here, as in the Job passage, tohu has cosmological implications: the NRSV translation “chaos” in Isa 45:18-19 seems apt.

The word bohu is found only three times in the Hebrew Bible, always following tohu: Genesis 1:2, Isaiah 34:11, and Jeremiah 4:23. Isaiah 34:11 comes from a bitter oracle against Edom (Isa 34:5-17), declaring its destruction as punishment for participating in Zion’s fall (for example, Ezek 35:1-15; Obad 10-16; Ps 137:7-9):

Screech owls and crows will possess it;

owls and ravens will live there.

God will stretch over it the measuring line of chaos [tohu]

and the plummet stone of emptiness [bohu] over its officials.

Throughout this poem, wild animals and plants have taken over lands formerly inhabited by people, making clear that tohu and bohu refer to wilderness here.

Jeremiah 4:23-26 reads,

I looked at the earth,

and it was without shape or form [tohu wabohu];

at the heavens

and there was no light.

I looked at the mountains

and they were quaking;

all the hills were rocking back and forth.

I looked and there was no one left;

every bird in the sky had taken flight.

I looked and the fertile land was a desert;

all its towns were in ruins

before the Lord,

before his fury.

Here as in the Isa 34:11, the context is a judgment oracle—indeed, a vision of judgment exacted not against a foreign enemy, but against Judah. Although there is no mention of creation in Jer 4:23, the allusions to Gen 1:1-3 are compelling: not only does this passage mention “heavens,” “earth,” and “light” (or rather, its absence), it is the only place in Scripture other than Gen 1:2 where the exact phrase tohu wabohu appears. As John Bright proposes in his classic commentary on Jeremiah,

in this poem, which is one of the most powerful descriptions of the Day of Yahweh in all prophetic literature, one might say that the story of Genesis i has been reversed: men, beasts, and growing things are gone, the dry land itself totters, the heavens cease to give their light, and primeval chaos returns. It is as if the earth had been ‘uncreated’; it is, if one cares to put it so, a ruin of ‘atomic’ proportions (Jeremiah, AB 21 [Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1965], 32-33)

Intriguingly, the judgment oracle that opens the book of Zephaniah also speaks of “uncreation,” in terms that also appear to allude to Genesis 1:

I will wipe out everything from the earth, says the LORD.

I will destroy humanity and the beasts;

I will destroy the birds in the sky and the fish in the sea.

I will make the wicked into a heap of ruins;

I will eliminate humanity from the earth, says the LORD (Zeph 1:2-3).

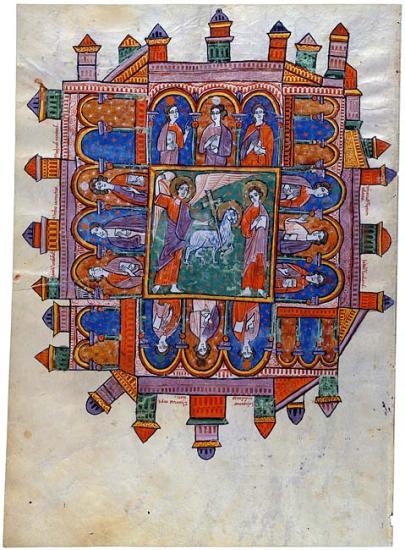

Zephaniah 1:3 lists the living creatures created by God on the fifth (birds and fish) and sixth (land animals, and humans) days of creation (Gen 1:20-31). However, as Michael De Roche has observed, they are listed in reverse order, moving backwards through the list from humanity (“Zephaniah 1:2-3: The ‘Sweeping’ of Creation.” VT 30 [1980]:106–107), so that creation is undone. The psalms bracketing Nahum and Habakkuk (Nah 1:2-11; Hab 3), which come right before Zephaniah, are poems celebrating the Divine Warrior, evoking the theme of creation by combat. The divine warrior who defeated chaos and brought an ordered world into being (Nah 1:3-4; Hab 3:8) can also undo that order and return the world to the chaos from which it came. In Zeph 1:2-3, as in Jer 4:23, Divine judgment is described as unmaking, the very opposite of creation: God’s ordered world returned to chaos.

How, then, should we render tohu wabohu in Gen 1:2? From his etymological research into tohu and bohu (The Earth and the Waters in Genesis 1 and 2: A Linguistic Investigation, JSOTSupp 8 [Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1989], 17-22), David Tsumura concludes “Hebrew tohu is based on a Semitic root *thw and means ‘desert’; the term bohu is also a Semitic term based on the root *bhw, ‘to be empty’” (Tsumura 1989, 155). Therefore, Tsumura insists “the phrase. . . has nothing to do with ‘chaos’ and simply means ‘emptiness’ and refers to the earth as an empty place, i.e., ‘an unproductive and uninhabited place’” (Tsumura 1989, 156). So too Claus Westermann insists tohu wabohu “is not a mythological idea but means desert, waste, devastation, nothingness” (Genesis 1—11: A Commentary, trans. John J. Scullion, S.J. [Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1984; from Biblischer Kommentar, Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener, 1974], 103).

The Vulgate, which in Gen 1:2 reads vacua erat et nihili, “it was empty and worthless,” could support this reading: the pre-creation earth was desolate and lifeless—a desert hostile to life. Similarly, in both Gen 1:2 and Jer 4:23, the Aramaic Targums render tohu wabohu as tsadya’ waroqanya’, “desolate and empty.” The Greek Septuagint, intriguingly, has aoratos kai akarskeuatos, “unseen and unready” (Brenton’s delightful 1870 translation reads, “unsightly and unfurnished”!) in Gen 1:2, and the single word outhen, “nothing,” in Jer 4:23. The Septuagint translators of Jeremiah treated tohu wabohu as a hendiadys: two words expressing a single idea. Indeed, Westermann proposed that bohu “is added only by way of alliteration” (Westermann 1984, 103). Accordingly, Robert Alter translates tohu wabohu in Gen 1:2 as “welter and waste” (The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary, Volume 1 [New York: W. W. Norton, 2019], 11), while William Brown proposes “void and vacuum” (The Seven Pillars of Creation: The Bible, Science, and the Ecology of Wonder [New York: Oxford, 2010], 34).

On the other hand, in its context in Genesis 1, tohu wabohu is immediately followed by a description of dark, restless, unruly water (Gen 1:2), which is most naturally read as a depiction of tohu wabohu. Together with the numerous clear parallels between Genesis 1:1—2:4a and the Enuma elish, this makes it difficult to hold, with Tsumura and Westermann, that tohu wabohu is not mythological, and has nothing to do with chaos. The “uncreation” texts in Jeremiah and Zephaniah support reading this phrase as chaos: the opposite of the ordered world, but out of which (as Bereshit Rabbah 1:5 reminds us) God’s creation has been established. The translation tradition going back to the KJV “without form, and void” seems valid (NRSV, “formless void,” CEB, “without shape or form,” JPSV, “unformed and void,” NIV “formless and empty,” NRSVUE, “without shape or form”). The point of Gen 1:1-2 is that the pre-creation world was chaos, upon which God’s word imposed order.

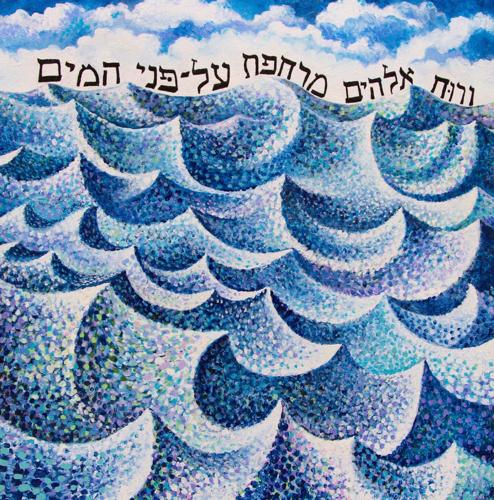

Yet, in this priestly vision of beginnings, not even chaos was devoid of Divine presence! For “God’s wind [Hebrew ruakh ‘elohim] swept over the waters” (Gen 1:2). The Hebrew ruakh is a marvelously multifaceted word. Its base meaning is “breath,” but by extension it can mean “wind,” or the enlivening and empowering agency within a person, hence “spirit” (as in the KJV and NIV; compare the use of the similarly mutifaceted Greek noun pneuma in John 3:5-6, 8). In Ezekiel’s vision of the dry bones, all three meanings of the word appear. Ezekiel prophesies to the four rukhot (the east, west, north, and south winds; Ezek 37:9), which blow over and into the corpses in the valley, filling them with ruakh (breath), so that “they came to life and stood on their feet, an extraordinarily large company” (Ezek 37:10). In the interpretation of this vision, the LORD promises the exiles, “‘I will put my breath [Hebrew rukhi] in you, and you will live. I will plant you on your fertile land, and you will know that I am the LORD. I’ve spoken, and I will do it. This is what the LORD says” (Ezek 37:14).

In Genesis 1:2 as well, we need not choose one meaning over the others: it is likely that all three meanings are present at once. The wind has mythic resonances with the Babylonian creation epic Enuma elish, where Marduk wields the winds as a weapon against the sea monster Tiamat. However, it is also appropriate to see this breeze as breathed by God onto the waters, and to understand ruakh as expressive of God’s spirit—God’s presence and person—even here.

![Title: Lift Every Voice and Sing, or, The Harp [Click for larger image view]](http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/lift-every-voice8927xc.jpg)

This past Sunday was Trinity Sunday. The lectionary

This past Sunday was Trinity Sunday. The lectionary

As with 1 John 5:7, this translation is not based on any ancient Greek text of Revelation, but on Erasmus’ sixteenth-century Textus receptus. Erasmus inserts ton sozomenon (“the ones who are saved”) after ta ethne (“the nations”) in Revelation 21:24. Neither the Latin Vulgate nor the majority Byzantine Greek text have this addition. Nestle-Aland’s critical edition of the Greek New Testament Novum Testamentum Graece doesn’t mention this insertion, even as a minor variant to be considered, and Metzger’s Textual Commentary doesn’t even discuss it.

As with 1 John 5:7, this translation is not based on any ancient Greek text of Revelation, but on Erasmus’ sixteenth-century Textus receptus. Erasmus inserts ton sozomenon (“the ones who are saved”) after ta ethne (“the nations”) in Revelation 21:24. Neither the Latin Vulgate nor the majority Byzantine Greek text have this addition. Nestle-Aland’s critical edition of the Greek New Testament Novum Testamentum Graece doesn’t mention this insertion, even as a minor variant to be considered, and Metzger’s Textual Commentary doesn’t even discuss it. So, what does text criticism mean to Bible students who do not know the original languages, and so lack access to the many texts behind the text on the page? First, the King James should not be your go-to study Bible. The language of the King James is beautiful and poetic: more often than not, the passages I have committed to memory are from its pages! For its day, the King James was an excellent translation. However, quite apart from the fact that we no longer speak in King James English, the translators in 1611 simply lacked access to the many ancient texts now available. Indeed, the oldest Hebrew manuscripts extant, the so-called Dead Sea Scrolls from Qumran, were unknown before the mid-twentieth century.

So, what does text criticism mean to Bible students who do not know the original languages, and so lack access to the many texts behind the text on the page? First, the King James should not be your go-to study Bible. The language of the King James is beautiful and poetic: more often than not, the passages I have committed to memory are from its pages! For its day, the King James was an excellent translation. However, quite apart from the fact that we no longer speak in King James English, the translators in 1611 simply lacked access to the many ancient texts now available. Indeed, the oldest Hebrew manuscripts extant, the so-called Dead Sea Scrolls from Qumran, were unknown before the mid-twentieth century.