This Sunday, I am honored to be teaching in the congregation served by my former student and current colleague in ministry, Jay Freyer: Beulah Presbyterian Church. So all day long, “Beulah” has been on my mind, and I’ve been humming and singing old gospel hymns from my youth:

O Beulah Land, sweet Beulah Land,

As on thy highest mount I stand,

I look away across the sea,

Where mansions are prepared for me,

And view the shining glory shore,

My Heav’n, my home forevermore!

I’m living on the mountain, underneath a cloudless sky;

I’m drinking at the fountain that never shall run dry;

O yes! I’m feasting on the manna from a bountiful supply,

For I am dwelling in Beulah Land.

So, what is Beulah Land? Where does this name come from? In the King James version, Isaiah 62:4 reads,

Thou shalt no more be termed Forsaken;

neither shall thy land any more be termed Desolate:

but thou shalt be called Hephzi-bah,

and thy land Beulah:

for the Lord delighteth in thee,

and thy land shall be married.

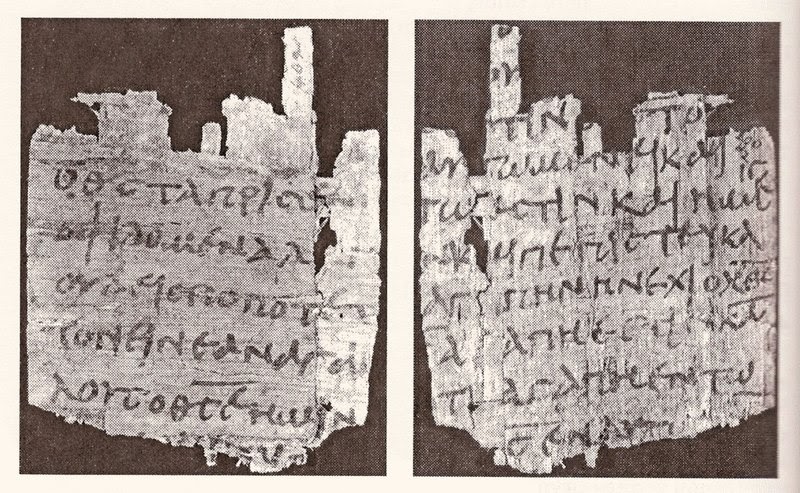

This passage comes from a section of the book (Isaiah 56–66) often called Third Isaiah, dating from soon after the return from Babylonian exile. By 587 BCE, the armies of Babylon had taken out all of Judah’s fortified cities, including Jerusalem. They deported large chunks of the populace, including the king, and destroyed the temple. So even after Babylon itself had fallen and the exiles came back, they found Judah devastated.

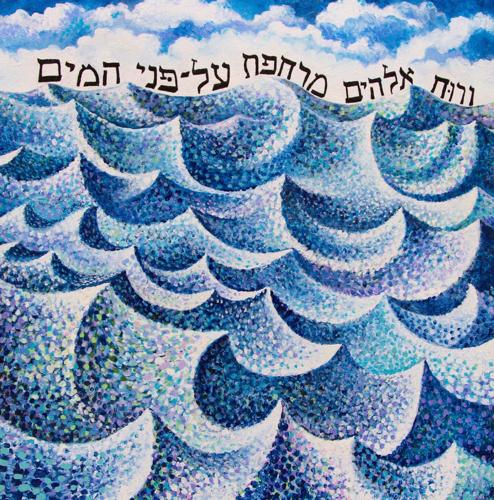

But the LORD promises to be with these returnees. Indeed, as often happens to brides on their wedding day, the LORD declares that Judah will be given a new name:

You shall no more be termed Forsaken [Hebrew Azuba],

and your land shall no more be termed Desolate [Hebrew Shemamah],

but you shall be called My Delight Is in Her [Hebrew Hephzibah]

and your land Married [Hebrew Beulah],

for the LORD delights in you,

and your land shall be married (Isa 62:4, NRSVue).

If Judah, now named Hephzibah and Beulah, is the bride, who is the groom? The very next verse declares,

For as a young man marries a young woman,

so shall your builder marry you,

and as the bridegroom rejoices over the bride,

so shall your God rejoice over you (Isa 62:5 NRSVue).

God will be to restored Judah, not as a king to his vassals, or a mistress to her slaves, but as a husband to a wife! The day of Judah’s restoration will be Judah’s wedding day!

In this metaphor, as my last blog discussed, God’s people are understood to be married to their LORD. No wonder “Beulah”–married–became shorthand in Christian hymnody for the blessedness of the Christian life, and the promise of God’s eternity. Indeed, the traditional United Methodist marriage service opens with these words:

Dearly beloved,

we are gathered together here in the sight of God,

and in the presence of these witnesses,

to join together this man and this woman

in holy matrimony,

which is an honorable estate, instituted of God,

and signifying unto us

the mystical union that exists between Christ and his Church;

which holy estate Christ adorned and beautified

with his presence in Cana of Galilee.

A wedding, it seems, is not just about this particular couple! The gathered congregation is reminded of their marriage, too: of the “mystical union that exists between Christ and his church.”

It is no accident that, in Hebrew, the words for city, land, and world are all feminine in gender. Indeed, although nouns in English lack gender, we too speak of “Mother Nature,” of our native language as our “mother tongue,” and of our high school or college as our “alma mater” (Latin for “bountiful mother”).

Back of this grammatical pattern is the ancient image of a city or a nation as a woman, the mother of its inhabitants. It is an easy step from that image to the notion of the city or nation as the bride of its god—as in Isaiah 62.

But of course, as all husbands and wives surely know, the wedding is not the marriage! After all, the LORD and Judah had been “married” before. The prophet Jeremiah wrote,

Go and proclaim to the people of Jerusalem,

The LORD proclaims:

I remember your first love,

your devotion as a young bride,

how you followed me in the wilderness,

in an unplanted land.

Israel was devoted to the LORD,

the early produce of the harvest.

Whoever ate from it became guilty;

disaster overtook them,

declares the LORD (Jer 2:2-3 CEB)

Indeed, the prophets treat this idea negatively most of the time, using unfaithfulness to marriage vows as a metaphor for false worship–idolatry becomes adultery (for example, Hosea 2:2–14; Jeremiah 3:1–10; Ezekiel 16:8-22).

A good marriage doesn’t just happen. It takes work for any marriage to work: attention to the other’s interests, needs, and concerns. But, without love, no amount of work will be enough, and with love, the work often does not feel like work at all!

God calls us Hephzibah and Beulah, friends. We are God’s delight, cherished and beloved. When we forget that, Jesus, as at the wedding in Cana, stands to ready to remind us—to once more turn the tepid, bland, insipid water of our religion into the rich red wine of true devotion.

AFTERWORD:

Beulah Presbyterian Church has quite a distinguished history! From their web site:

In 2014, Beulah Presbyterian Church in Churchill marked its 230th anniversary of being a place of Christian worship. It has a long history, deeply intertwined with the early settlement of English-speaking people in the area. Worship has continued there since a gathering of soldiers led by British Brig. Gen. John Forbes who defeated the French at Fort Duquesne in 1758.

The Presbytery officially recognized the church in 1784 and the church– originally called Bullock Pens for the soldiers’ cattle yard there, later called Pitt Township Presbyterian Church — was named Beulah in 1804.

After meeting in two earlier log structures (one a simple cabin, the second a cross-shaped building), worshippers built the first brick church in 1837, and that building still stands at Beulah Road and McCrady Road.

The cemetery holds the graves of veterans from Gen. Forbes’ troops, as well as men who fought in the Revolutionary War, Civil War, World War I and World War II. Grave markers for men, women and children carry names now found on area streets and landmarks: Johnston, McCrea, Lindberg, MacFarlane, Kelly.

Early members of the church, believed to be one of the first Christian churches west of the Alleghenies, later founded other Presbyterian churches in the region: East Liberty (1828), Crossroads (1836), Hebron (1849), Wilkinsburg (1866), Turtle Creek (1878), Forest Hills (1904).

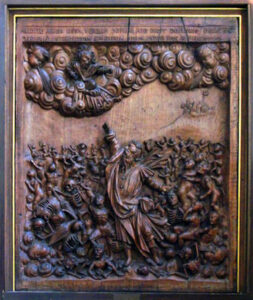

God asks Ezekiel, “Human one, can these bones live again?” (37:3). The obvious answer is no—there is no life, and no possibility of life, in this place! The bodies strewn across the valley are not only dead, they are long dead (37:2). But since his call, Ezekiel has seen (see

God asks Ezekiel, “Human one, can these bones live again?” (37:3). The obvious answer is no—there is no life, and no possibility of life, in this place! The bodies strewn across the valley are not only dead, they are long dead (37:2). But since his call, Ezekiel has seen (see  Again God speaks: “Prophesy to the breath; prophesy, human one! Say to the breath, The Lord God proclaims: Come from the four winds, breath! Breathe into these dead bodies and let them live” (37:9).

Again God speaks: “Prophesy to the breath; prophesy, human one! Say to the breath, The Lord God proclaims: Come from the four winds, breath! Breathe into these dead bodies and let them live” (37:9).

![Title: Descent of the Holy Spirit [Click for larger image view]](https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/El_Greco_006.jpg)

This week, as Christian pastors and laity alike turn in their devotions to reflection on Jesus’ betrayal, trial, torture, and death, it seems appropriate to turn to the witness of the apostle Paul, our first-century peer.

This week, as Christian pastors and laity alike turn in their devotions to reflection on Jesus’ betrayal, trial, torture, and death, it seems appropriate to turn to the witness of the apostle Paul, our first-century peer. So–when and how did Jesus send him? In

So–when and how did Jesus send him? In  Paul freely acknowledges that this is absurd on its face:

Paul freely acknowledges that this is absurd on its face: This means that the death of Jesus on the cross is not just about Jesus (

This means that the death of Jesus on the cross is not just about Jesus ( In our American date format, today is 3/14, which is also, as it happens, pi to the first two digits–making March 14 Pi Day! To refresh from high school geography, pi is the ratio between the circumference of a circle and its diameter–so, if you know the radius of a circle, you can use pi to calculate its circumference (2πr) or its area (πr squared: prompting the very bad pun, “No, pie are round; cornbread are square”). That ratio is, approximately, 3.14159–although mathematicians have now calculated its value out

In our American date format, today is 3/14, which is also, as it happens, pi to the first two digits–making March 14 Pi Day! To refresh from high school geography, pi is the ratio between the circumference of a circle and its diameter–so, if you know the radius of a circle, you can use pi to calculate its circumference (2πr) or its area (πr squared: prompting the very bad pun, “No, pie are round; cornbread are square”). That ratio is, approximately, 3.14159–although mathematicians have now calculated its value out

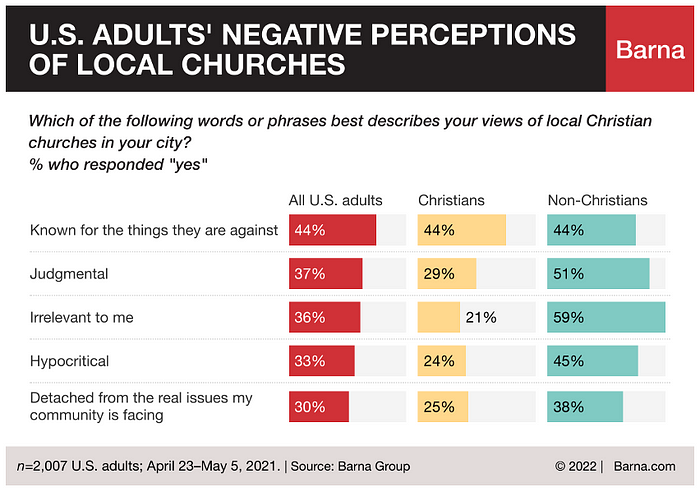

Evangelical pastor and author Brian Zahnd is concerned that much of American Christianity today is characterized, not by service or kindness, but by fear and anger–even hatred. Challenging his fellow pastors and leaders, Zahnd says,

Evangelical pastor and author Brian Zahnd is concerned that much of American Christianity today is characterized, not by service or kindness, but by fear and anger–even hatred. Challenging his fellow pastors and leaders, Zahnd says,