This Sunday, Palm Sunday, is also called Passion Sunday, as it marks the beginning of Holy Week. Four of the Old Testament readings for Holy Week are poems from Isaiah 40—55: a portion of this prophetic book commonly called Second Isaiah, set in the Babylonian exile. These four passages, Isaiah 42:1-9; 49:1-7; 50:4-11; and 52:13—53:12, are called the Servant Songs. All deal with the Servant of the LORD, a mysterious figure whose mission involves not only the deliverance of Israel, but also the transformation of the world. Appropriately, the Hebrew Bible reading for Good Friday’s remembrance of Jesus’ trial, crucifixion, death, and burial is the fourth Song, Isaiah 52:13—53:12: the song of the Suffering Servant.

This Sunday, Palm Sunday, is also called Passion Sunday, as it marks the beginning of Holy Week. Four of the Old Testament readings for Holy Week are poems from Isaiah 40—55: a portion of this prophetic book commonly called Second Isaiah, set in the Babylonian exile. These four passages, Isaiah 42:1-9; 49:1-7; 50:4-11; and 52:13—53:12, are called the Servant Songs. All deal with the Servant of the LORD, a mysterious figure whose mission involves not only the deliverance of Israel, but also the transformation of the world. Appropriately, the Hebrew Bible reading for Good Friday’s remembrance of Jesus’ trial, crucifixion, death, and burial is the fourth Song, Isaiah 52:13—53:12: the song of the Suffering Servant.

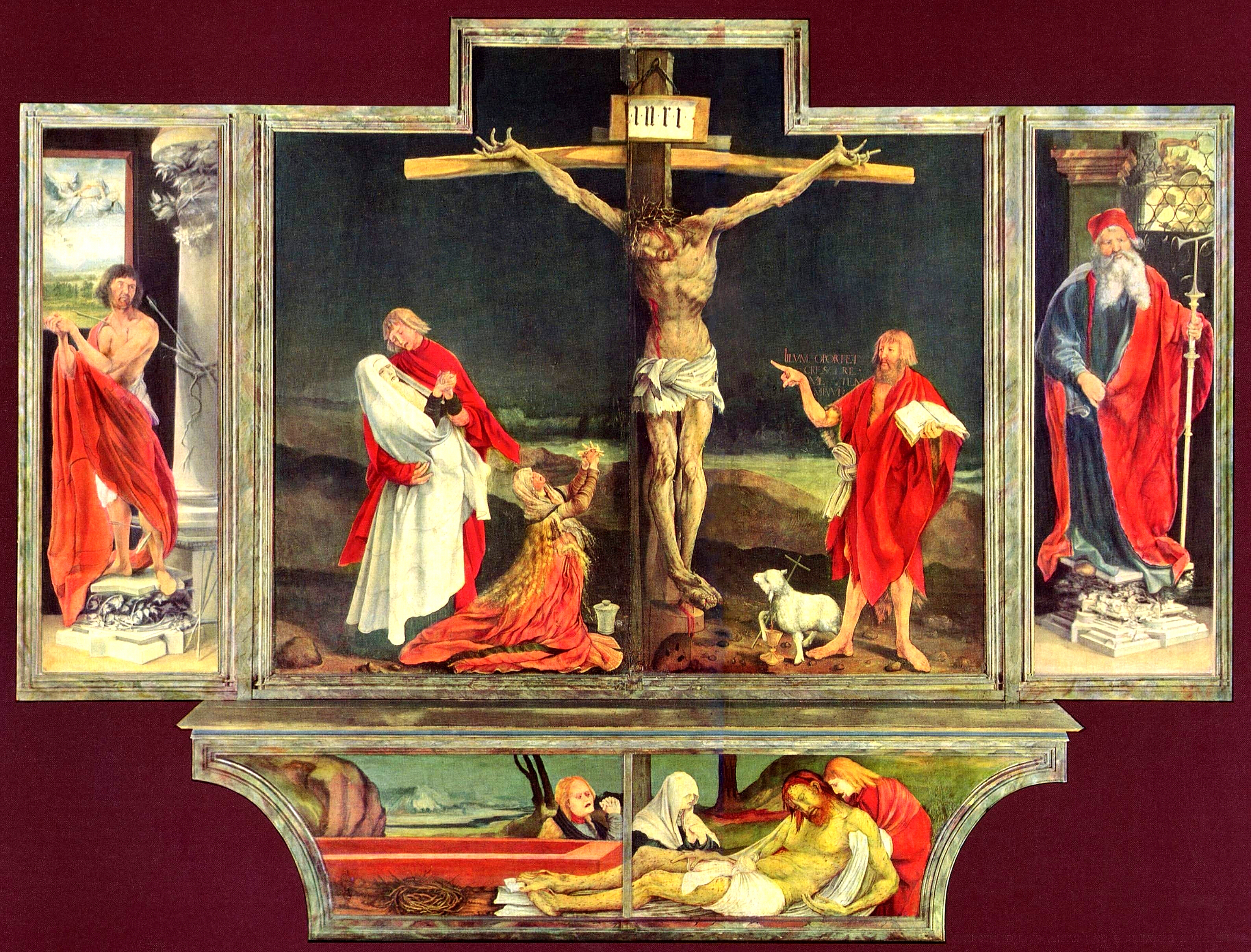

The suffering of the Servant is a common theme in the Songs, from the first Song, where the world threatens to crush the Servant (Isa 42:4) to Isaiah 50:6, where the Servant bares his back to the smiters, and offers his cheek “to those who pulled out the beard.”

However, the Servant’s suffering is the major theme of the fourth and final Song:

He was despised and avoided by others;

a man who suffered, who knew sickness well.

Like someone from whom people hid their faces,

he was despised, and we didn’t think about him (Isa 53:3).

The Servant’s suffering is never accidental, or incidental. Rather, the Servant suffers deliberately, purposively: in solidarity with others. So, the vindication of the Servant becomes their vindication as well; when the Servant is strengthened, his fellow-sufferers too find strength.

Christian readers have long seen Jesus in Isaiah’s Suffering Servant of the LORD. So, in Acts 8:26-38, when the Ethiopian eunuch asks if the prophet speaks in Isa 53 “about himself or about someone else,” Philip wastes no time in sharing with him “the good news about Jesus.”

In 1 Peter 2:21-25, that writer, alluding to Isaiah 53, declares of Jesus

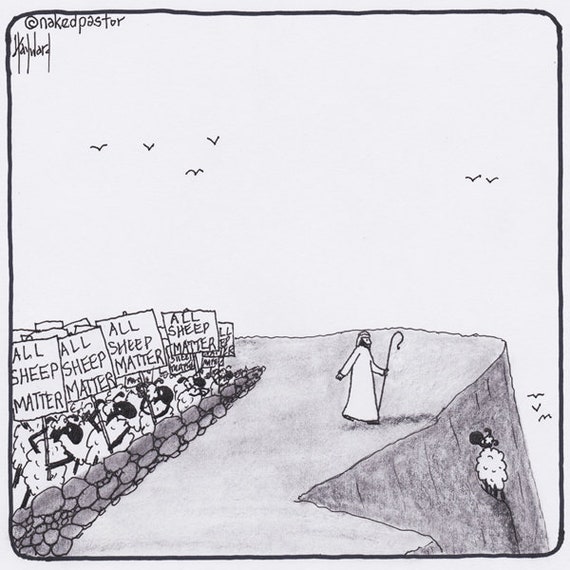

He committed no sin, and no deceit was found in his mouth. When he was abused, he did not return abuse; when he suffered, he did not threaten; but he entrusted himself to the one who judges justly. He himself bore our sins in his body on the cross, so that, free from sins, we might live for righteousness; by his wounds you have been healed. For you were going astray like sheep, but now you have returned to the shepherd and guardian of your souls.

We Christians still cannot help but see Jesus in Isaiah’s Servant. But that does not mean that we must, in triumphalist fashion, see Second Isaiah as predicting Jesus’ coming; as though the prophet’s words had no meaning for his own time or people.

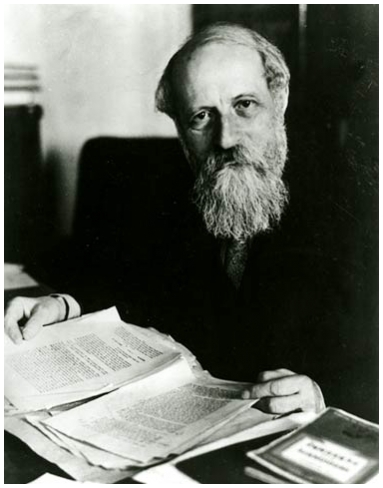

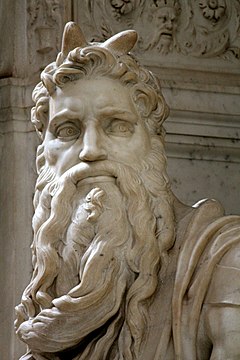

The great Jewish philosopher Martin Buber suggested that the Servant Songs do not describe one particular person, but rather set forth the way of the Servant, a new understanding of Israel’s past and future particularly as revealed through suffering. The Servant’s way is “the work born out of affliction,” culminating in “the liberation of the subject peoples, laid upon the servant, the divine order of the expiated world of the nations, which the purified servant as its ‘light’ has to bring in, the covenant of the people of the human beings with God, the human center of which is the servant” (Martin Buber, The Prophetic Faith, trans. Carlyle Witton-Davies [New York: Macmillan, 1949], 229). The way of the Servant is the path of redemptive suffering deliberately chosen, which will render the tangled history of God’s people meaningful. Jesus, we can certainly say, deliberately set out to follow that way, which led him inexorably to the cross.

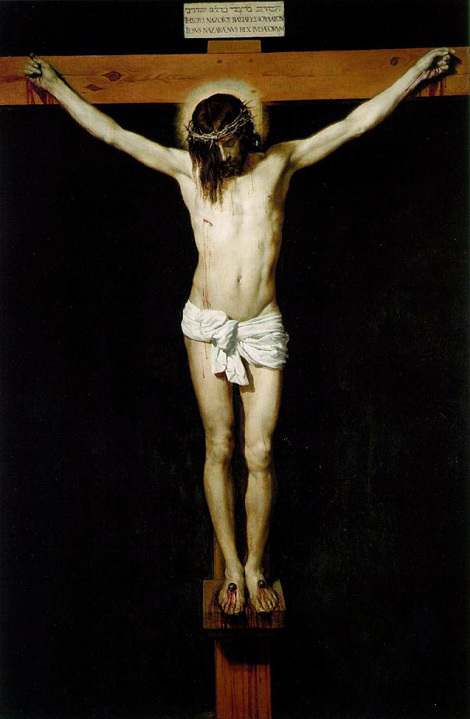

Jesus has been linked to Isaiah 52:13—53:12 in particular, not only because of the Servant’s innocent suffering on behalf of others (Isa 53:4-6), but specifically because of Isaiah 53:10, where many English translations read that the Servant’s life has been made (or will be made) “an offering for sin.”

Christians have often understood Jesus’ death on the cross in just this way: as a sacrifice for sin. In our New Testament, the book of Hebrews understands Jesus as at once high priest and sacrifice, offering himself as a sin offering for the world (Heb 9—10). There are some indications that Jesus may have thought of his own death in that way. So, in Matthew’s account of the Last Supper.

He took a cup, gave thanks, and gave it to them, saying, “Drink from this, all of you. This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many so that their sins may be forgiven” (Matt 26:27-28, CEB).

Notice, though, that this passage uses no sacrificial language, saying only that it is now, in his death, that Jesus fulfills the meaning of his name: Yeshua, that is “savior,” for “he will save his people from their sins” (Matt 1:21).

Similarly, it is unclear that Paul intended us to see Jesus’ death as a sin offering. That may seem a strange claim, in light of Romans 3:23-25 (NRSV):

since all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God; they are now justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as a sacrifice of atonement by his blood, effective through faith.

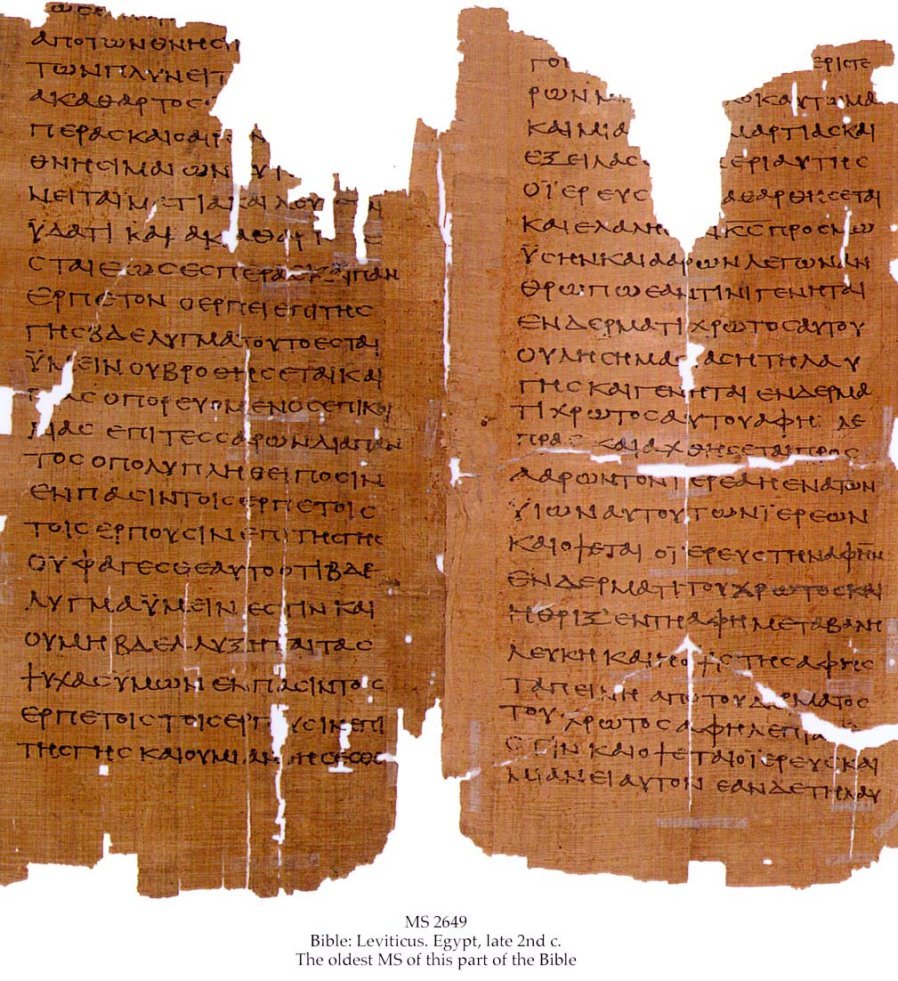

But the Greek word translated “sacrifice of atonement” in the NRSV (the KJV has “propitiation”) is hilasterion. This Greek word is used in Leviticus 16, the biblical description of Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. It refers, however, not to the sin sacrifice or to the scapegoat in that ritual, but rather to the lid of the ark, where the blood of the sacrifice is applied (Hebrew kapporet). At least in this famous passage, Paul refers to the cross not as a sacrifice for sin, but rather as the place of atonement (see the NRSV translator’s footnote on this phrase), where God and humanity are reconciled.

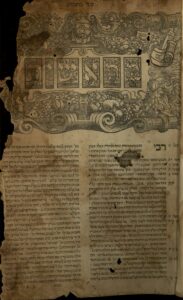

Another translation problem occurs in Isaiah 53:10. Although several English translations have “offering for sin,” the word “sin” does not appear in this verse, and the Hebrew word for the offering is not khattat (Hebrew for the sin offering), but ‘asham: used in Leviticus 5:14-26 for what is commonly called the “guilt offering.”

While ‘asham is often translated as “guilt,” it more precisely means “to incur liability,” and is used for payment of damages. This is the only offering in ancient Israel’s sacrificial system that involves a fine as well as a sacrifice–indeed, for which a fine can be substituted. Jewish scholars Baruch Schwartz (in the Jewish Study Bible) and Jacob Milgrom (in the HarperCollins Study Bible) both propose “reparation offering” as a better translation. In the NRSV and the NRSVue, this section of Leviticus carries the heading “Offerings with Restitution.”

As the ‘asham is described in Leviticus, it is an offering to be made when an act has been performed, even accidentally, that brings defilement upon the community or upon the holy things. So, this is an offering for when you suspect you have done something wrong, but do not know what–making the traditional rendering “guilt offering” fitting after all! An ‘asham is offered when something isn’t right, in my life or in my community, but I can’t say what it is–so, perhaps I have somehow, inadvertently, brought defilement upon the community and the holy things. The ‘asham, we could say, addresses free-flowing Angst!

What might this mean in the context of our Song? First, whatever else Isa 53:10 may mean, it does not mean that the Servant is a sacrifice for sin. In the CEB, this verse is translated “his life is offered as restitution”–a more accurate rendering, but what might that mean? Translator’s notes in the NRSV and NRSVue acknowledge, “Meaning of Heb uncertain.” Perhaps the point, as the Song as a whole implies, is that by identifying with those who suffer guilt, pain, and shame, the Servant eases that suffering, mysteriously shifting it onto himself.

Perhaps this is a better way of thinking about the suffering of Jesus, too. The Oxford English Dictionary dates our English word “atonement” to the early 16th century, when it was coined out of the phrase “at one”–influenced by the Latin word adunamentum (“unity”), and an older word, “onement:” from the obsolete verb form, “to one,” meaning “to unite.” The word was particularly used to talk about the reconciliation of God and humanity through Christ. What “atonement” originally meant was not the assuaging of divine wrath with a blood sacrifice, but being reunited (“at one”) with God. As the apostle Paul writes:

If we were reconciled to God through the death of his Son while we were still enemies, now that we have been reconciled, how much more certain is it that we will be saved by his life? And not only that: we even take pride in God through our Lord Jesus Christ, the one through whom we now have a restored relationship with God (Romans 5:6-11).

In Christ’s death, we are reconciled (Greek katalasso) to God. The gap between humanity and divinity is bridged. In Jesus, who is fully human and fully divine, God experiences all that being human means, in joy and in sorrow. Life learns what it is to die. Absolute power learns what it is to be weak. God Godself experiences God-forsakenness. In Christ’s resurrection, we mortals are given the hope and the promise of our own deliverance from death. By entering into our life, and even into our death, Jesus draws God near to us, and us near to God. He brings God’s divinity down to where we are, and lifts our humanity up to where God is.

Of course, if Isaiah 52:13—53:12 cannot be safely restricted to a sacrificial act which Jesus alone could, and did, do, we are brought back to asking what this passage may mean for the living of our lives. But after forty days of penitential Lenten reflection, we are likely eager to move on. Palm Sunday leads to Good Friday, of course, but that in turn leads to Easter–and we are naturally eager to celebrate Christ’s resurrection, and the promise of our own!

But, let us not hurry to the empty tomb too quickly, friends. Let us stay with the cross awhile, and ask what it might mean for us to follow Jesus on the way of the Servant; to surrender authority and privilege, and stand with the suffering and oppressed. After all, did Jesus not say, ““All who want to come after me must say no to themselves, take up their cross, and follow me” (Matt 16:24)?

1 Peter definitely sees the cross in Isa 53, but does not therefore think that we are relieved of the responsibility to walk in this way ourselves. Indeed, this Christian writes, “You were called to this kind of endurance, because Christ suffered on your behalf. He left you an example so that you might follow in his footsteps” (1 Peter 2:21).

So too, the writer of Hebrews calls Jesus “faith’s pioneer and perfecter. He endured the cross, ignoring the shame, for the sake of the joy that was laid out in front of him, and sat down at the right side of God’s throne” (Heb 12:2).

What might it mean to follow such a pioneer—to, in the words of the old Gospel hymn, “go with him, with him, all the way”? What might it mean to say, with Paul, “I have been crucified with Christ” (Gal 2:20)?

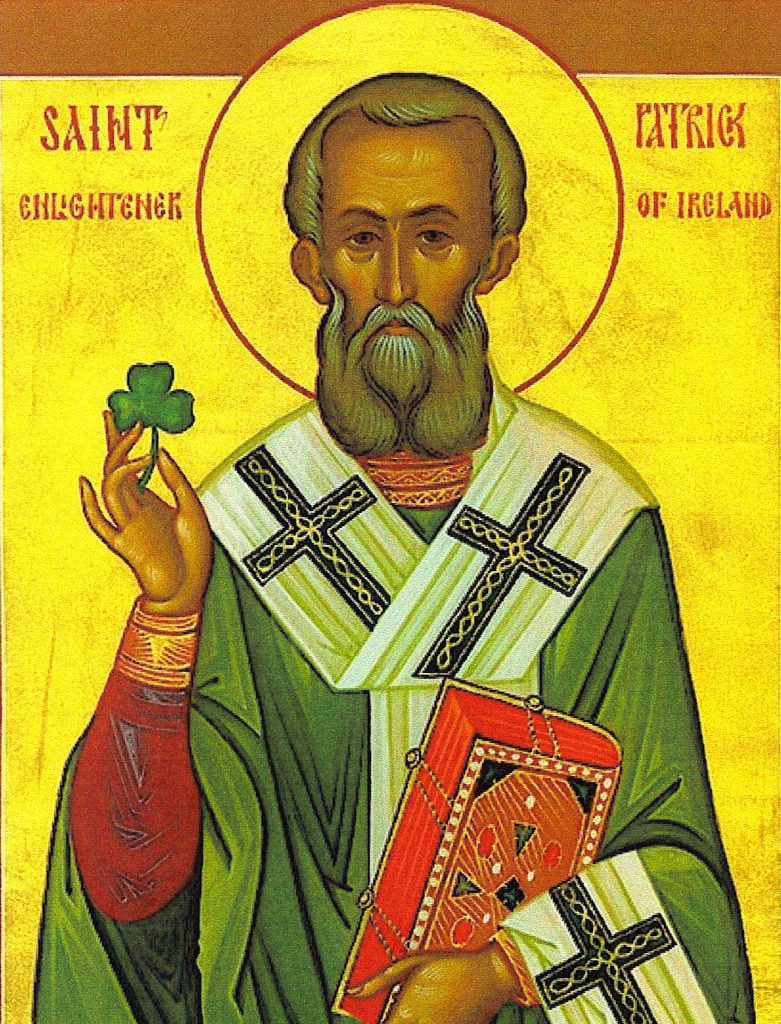

Friday March 17 is the feast of Saint Pádraig–better known as Patrick, patron saint of Ireland. St. Patrick’s teaching embraced God’s presence manifest in God’s creation–as in the tradition that Patrick used the shamrock to teach the Trinity. Of course, as a metaphor for God’s unity in three persons, the shamrock

Friday March 17 is the feast of Saint Pádraig–better known as Patrick, patron saint of Ireland. St. Patrick’s teaching embraced God’s presence manifest in God’s creation–as in the tradition that Patrick used the shamrock to teach the Trinity. Of course, as a metaphor for God’s unity in three persons, the shamrock  This week, I have been remembering the controversial depiction of the Trinity in William P. Young’s novel The Shack. My covenant group at St. Paul’s UMC read this book, but I honestly do not believe I ever finished it. Wendy reminds me that I was dismissive of The Shack, scornful of what I saw as its naïveté and its theological shortcomings.

This week, I have been remembering the controversial depiction of the Trinity in William P. Young’s novel The Shack. My covenant group at St. Paul’s UMC read this book, but I honestly do not believe I ever finished it. Wendy reminds me that I was dismissive of The Shack, scornful of what I saw as its naïveté and its theological shortcomings.

While full-blown Trinitarian language is wanting in the texts of Scripture, the Gospel of John comes very close.

While full-blown Trinitarian language is wanting in the texts of Scripture, the Gospel of John comes very close.  This language in turn reflects the struggle of the sages of ancient Israel to find a way of talking about God as, on the one hand, separate from the world and its objects, and on the other, as intimately involved and engaged with the world. Particularly in

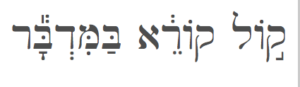

This language in turn reflects the struggle of the sages of ancient Israel to find a way of talking about God as, on the one hand, separate from the world and its objects, and on the other, as intimately involved and engaged with the world. Particularly in  Lady Wisdom says, “The LORD created me [Hebrew qanani; perhaps better “acquired me,” that is, as a wife] at the beginning of his way, before his deeds long in the past” (

Lady Wisdom says, “The LORD created me [Hebrew qanani; perhaps better “acquired me,” that is, as a wife] at the beginning of his way, before his deeds long in the past” (![Title: St. Savin - Calling of Abraham [Click for larger image view]](https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/00002314.jpg)

But what would this word have meant to the writers, and hearers, of the Gospels? The verb metamorphoo is not used in the Septuagint (the Greek translation of Jewish Scripture), and in our New Testament, it appears only four times. Two of these are the accounts of Jesus’ transfiguration in Matthew and Mark (

But what would this word have meant to the writers, and hearers, of the Gospels? The verb metamorphoo is not used in the Septuagint (the Greek translation of Jewish Scripture), and in our New Testament, it appears only four times. Two of these are the accounts of Jesus’ transfiguration in Matthew and Mark (

![Title: Star of Bethlehem with Pomegranate Trees [Click for larger image view]](https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/ACT0012.jpg)

If you are wondering what any of this has to do with the season of Advent, or with the birth of our Lord, may I remind you that the alternate Psalm for this coming Sunday is Luke’s Song of Mary (

If you are wondering what any of this has to do with the season of Advent, or with the birth of our Lord, may I remind you that the alternate Psalm for this coming Sunday is Luke’s Song of Mary (