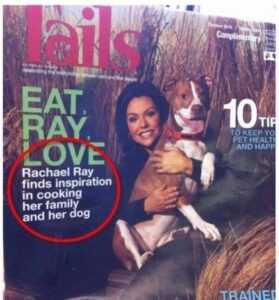

I love this meme, which comically demonstrates the importance of proper punctuation. Intended, of course, was “Rachael Ray finds inspiration in cooking, her family, and her dog.” For all I know, this meme has photoshopped out the punctuation for comic effect. But without those commas, this cover announces a horror show! On Facebook, I captioned this picture “Punctuation saves lives!”

But what about written languages–including our biblical languages!–which lack punctuation? How are such confusions avoided? The short answer is that, frequently, they are not. Generally, the reader has to rely on context cues to the intended meaning of an ambiguous passage.

Which leads us to the Gospel for this second Sunday of Advent, Matthew 3:1-12, concerning John the Baptist. In all four Gospels, John is introduced by a quotation from Isaiah. In the recent Updated Edition of the NRSV, Matthew 3:3 reads,

This is the one of whom the prophet Isaiah spoke when he said,

“The voice of one crying out in the wilderness:

‘Prepare the way of the Lord;

make his paths straight.’ ”

However, if you look up the Isaiah passage quoted, you will find:

A voice cries out:

“In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord;

make straight in the desert a highway for our God” (Isaiah 40:3, NRSVUE).

You see the problem. Where should the comma go? Does Isaiah refer to a voice crying in the wilderness, “Prepare the way of the Lord,” or does the voice cry, “In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord”? Does the text of Isaiah give us any way to resolve this ambiguity?

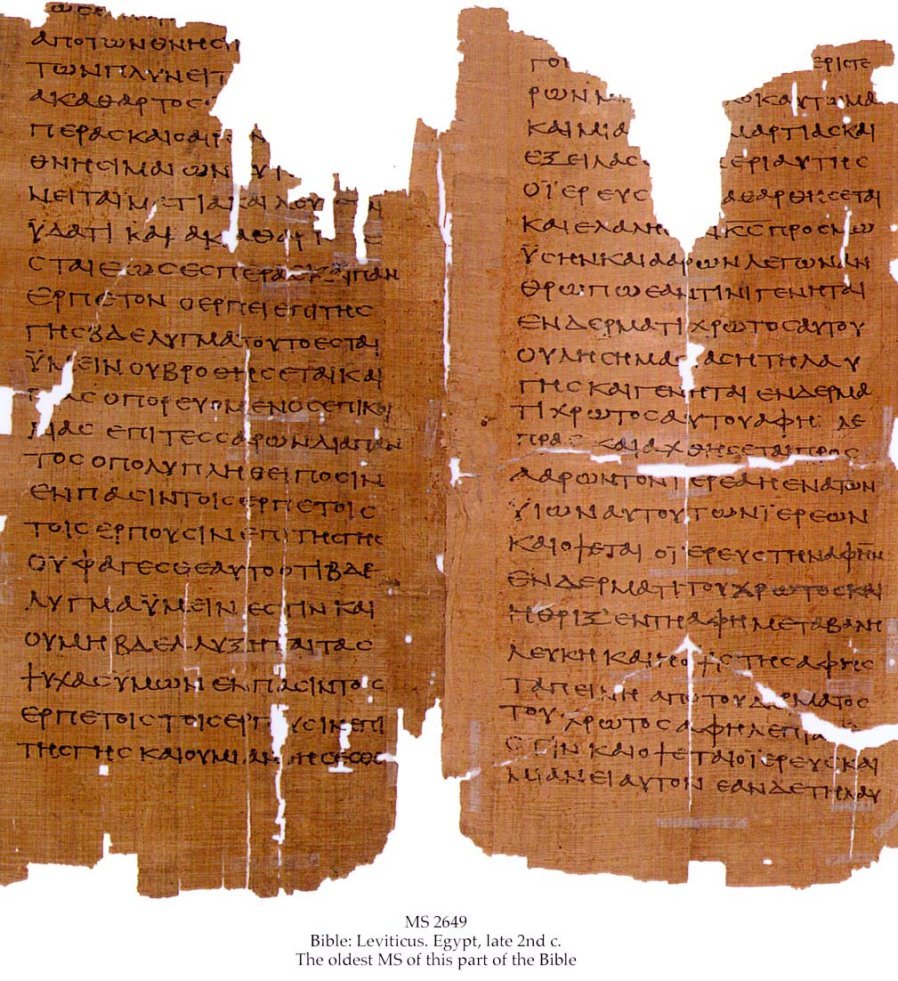

Matthew (like Mark before him) is quoting directly from the Septuagint, the Greek translation of Jewish Scripture that was the Bible of the earliest church. Although later Greek texts do use punctuation and capital letters to enable the reader to distinguish sentences and phrases, the original text did not–indeed, often there was not even a space between words!

For the gospel writers, there would not have been any clear indication of where the break belonged–and in any case, motivated as they were to find texts foreshadowing and interpreting Jesus’ life and work, we can certainly understand why they would read Isaiah 40:3 as referring to John the Baptist, “a voice crying in the wilderness.”

Mark, likely the first Gospel writer and so the first one to make this connection, actually conflates Isaiah 40:3 with another text:

The beginning of the good news about Jesus Christ, God’s Son, happened just as it was written about in the prophecy of Isaiah:

Look, I am sending my messenger before you.

He will prepare your way,

a voice shouting in the wilderness:

“Prepare the way for the Lord;

make his paths straight” (Mark 1:1-3).

The first two lines of this quotation actually do not come from Isaiah at all. They allude to two passages from Malachi. The first is Malachi 3:1-4:

Look, I am sending my messenger who will clear the path before me;

suddenly the Lord whom you are seeking will come to his temple.

The messenger of the covenant in whom you take delight is coming,

says the Lord of heavenly forces.

Who can endure the day of his coming?

Who can withstand his appearance?

He is like the refiner’s fire or the cleaner’s soap.

He will sit as a refiner and a purifier of silver.

He will purify the Levites

and refine them like gold and silver.

They will belong to the Lord,

presenting a righteous offering.

The offering of Judah and Jerusalem will be pleasing to the Lord

as in ancient days and in former years.

Malachi comes at the end of the Book of the Twelve, and in the Christian Bible, at the end of the Old Testament. Far from being moved to repentance and change by Malachi’s call to reform, his audience says, “Anyone doing evil is good in the Lord’s eyes,” or “He delights in those doing evil,” or “Where is the God of justice?”(Mal 2:17). In other words, Malachi’s community believes that either God does not see what they do, or that God does not care.

Malachi gives assurance that these questions and doubts are about to be addressed, for “suddenly the LORD whom you are seeking will come to his temple” (Mal 3:1). Those who piously claim to delight in God’s covenant will soon have the opportunity to express their gratitude personally!

Malachi proclaims not only the advent of the LORD, but also of the LORD’s messenger. In Hebrew, “my messenger” is mal’akhi–the same word that appears at the beginning of the book (Mal 1:1), where mal’akhi is the one through whom this book’s message of judgment is communicated. While we might expect a name like Malachiah (“the LORD’s messenger”), “my messenger” seems an unlikely name for any parent to give a child! Probably, then, the prophet is anonymous; but is called Mal’akhi by the book’s editors because of Malachi 3:1.

But already within the editing of Malachi, we see further reflections on the identity of this enigmatic figure. The second Malachi passage to which Mark alludes in his quotation from “Isaiah” is the conclusion to this book:

See, I will send you the prophet Elijah before the great and terrible day of the Lord comes. He will turn the hearts of parents to their children and the hearts of children to their parents, so that I will not come and strike the land with a curse (Mal 4:5-6 NRSVUE [3:23-24 in the Hebrew text]).

The prophetic forerunner of the day of the LORD has become Elijah, who was taken alive into the heavens in a chariot of fire (2 Kgs 2:11) and so could be called upon for this task!

In Christian Scripture, Jesus is the one who comes to cleanse his people from their sins (Mal 3:2-3), and John the Baptist becomes the “messenger” sent to proclaim Jesus’ coming (see the quotes of Mal 3:1 at Matt 11:10; Mark 1:2; Luke 1:76; 7:27), and “Elijah who is to come” (Matt 11:14; cf. Matt 17:10-11; Mark 9:11-12; Luke 1:17). By linking these passages from Malachi to Isa 40:3, Mark laid the foundation for this reading.

Augustine too on the one hand describes John the Baptist as the “messenger” of Malachi 3:1 (Tractates on the Gospel of John 14.10.1), and on the other relates Malachi 3:1-2 to Christ: both his first coming (reading the Lord coming to “his temple” as a reference to the incarnation; see Matt 26:59-61; Mark 14:55-59; John 2:19-21, where the “temple” refers to Jesus’ body) and also to his second coming at the end of time (“Who can endure the day of his coming?,” Mal 3:2; cf. The City of God 18:35; 20:25).

Perhaps as you have been reading this blog, the musical setting of Malachi 3:1-3 from George Handel’s famous oratorio The Messiah has been playing in your head–as it has in mine. Charles Jennens, who composed the libretto for this oratorio, doubtless picked this passage for inclusion because, like Augustine, he regarded it as a reference Christ’s first and second coming.

Coming back to Isaiah 40:3 in the Hebrew text: originally, written Hebrew recorded only the consonants, and lacked any system of punctuation. However, a system of marks above and below the line developed in the scribal tradition, and was used by the scribes (called “Masoretes”) to record what they heard when the text was read aloud. This included not only the vowel sounds (indicated by marks called “pointing;” these marks are still used, sparsely, in modern Hebrew), but also rising and falling inflections and pauses (indicated by accent marks)–even, some think, musical tones for chanting!

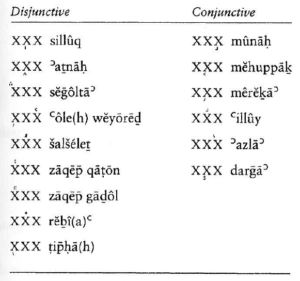

As this chart (from Choon Leong Seow, A Grammar for Biblical Hebrew, Revised Edition [Nashville: Abingdon, 1995], 65) shows, the accent marks are divided into conjunctive accents, which link a word to the word following, and disjunctive accents, which mark a break–acting like commas, semicolons, and periods in English.

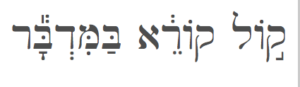

The most common Hebrew accent, called the zaqeph qaton, is essentially a Masoretic comma. In the Masoretic text of Isaiah 40:3, the verb qore’ (“cry, call out”) is marked with a zaqeph qaton, showing that the Masoretes heard a break here. In the printed text of the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, the standard critical text of the Hebrew Bible, this disjunction is emphasized even more by a line break: qol qore’ (“A voice cries”) has a line to itself, while bammidbar (“In the wilderness”) opens the line following. Even without those explicit markings, however, context clues would lead us to this reading.

Isaiah 40– 55 is addressed to exiles (Isa 45:11– 13), who now anticipate a return home— specifically, from Babylon (see 43:14; 48:20). Jerusalem and the villages of Judah are described as abandoned ruins (44:24– 26). Sarcastic reference is made to specific Babylonian rites, such as the cult processional of Bel Marduk patron god of Babylon and his son Nebo, scribe of the gods (46:1– 2); and the magical practice of astrological divination (47:12– 13). Second Isaiah, as Isaiah 40–55 is commonly called, can be dated to the mid- sixth century, shortly before the fall of Babylon—and about 150 years after Isaiah of Jerusalem.

An important theme in these chapters is the promise of a second exodus. Just as in the first exodus God delivered Israel from slavery in Egypt, so in this new exodus, God delivers the people from the bondage of exile in Babylon. Indeed, recollection of Israel’s deliverance through the Red Sea in the first exodus is supplanted by the new thing that God will now do:

I am the LORD, your holy one,

Israel’s creator, your king!

The LORD says—who makes a way in the sea

and a path in the mighty waters,

who brings out chariot and horse,

army and battalion;

they will lie down together and will not rise;

they will be extinguished, extinguished like a wick.

Don’t remember the prior things;

don’t ponder ancient history.

Look! I’m doing a new thing;

now it sprouts up; don’t you recognize it?

I’m making a way in the desert,

paths in the wilderness (Isa 43:15– 19).

Just as in the first exodus, God had led God’s people through the wilderness (see Exod 13:21– 22), so now the prophet promises that God will make a way leading through the wilderness back home (Isa 42:15– 16; 49:8– 12; 55:12– 13). Indeed, in Isaiah 40:3-5, quoted in today’s Gospel reading, Second Isaiah declares that God will build a highway for the exiles’ safe return:

A voice is crying out:

“Clear the Lord’s way in the desert!

Make a level highway in the wilderness for our God!

Every valley will be raised up,

and every mountain and hill will be flattened.

Uneven ground will become level,

and rough terrain a valley plain.

The Lord’s glory will appear,

and all humanity will see it together;

the Lord’s mouth has commanded it.”

The Gospel writers, by identifying John the Baptist as “The voice of one crying in the wilderness,” read Isaiah 40:3 differently than the Hebrew scribes who have given us the text back of our Old Testament. From the best evidence, it appears that those scribes have accurately communicated the intent of Second Isaiah. Does this matter? Only, I would suggest, if we insist on retrojecting the Gospel reading into the Hebrew Bible. We can recognize Second Isaiah’s distinctive message and purpose, and still recognize that the purpose of this text in its historical setting does not exhaust its meaning.

Within Christian Scripture, this passage expressing God’s gracious concern and providential care of the Babylonian exiles has come to express God’s gracious concern and providential care in other ways, too. By sending John the Baptist, God showed God’s care for Jesus, providing for him a support, and perhaps a mentor.

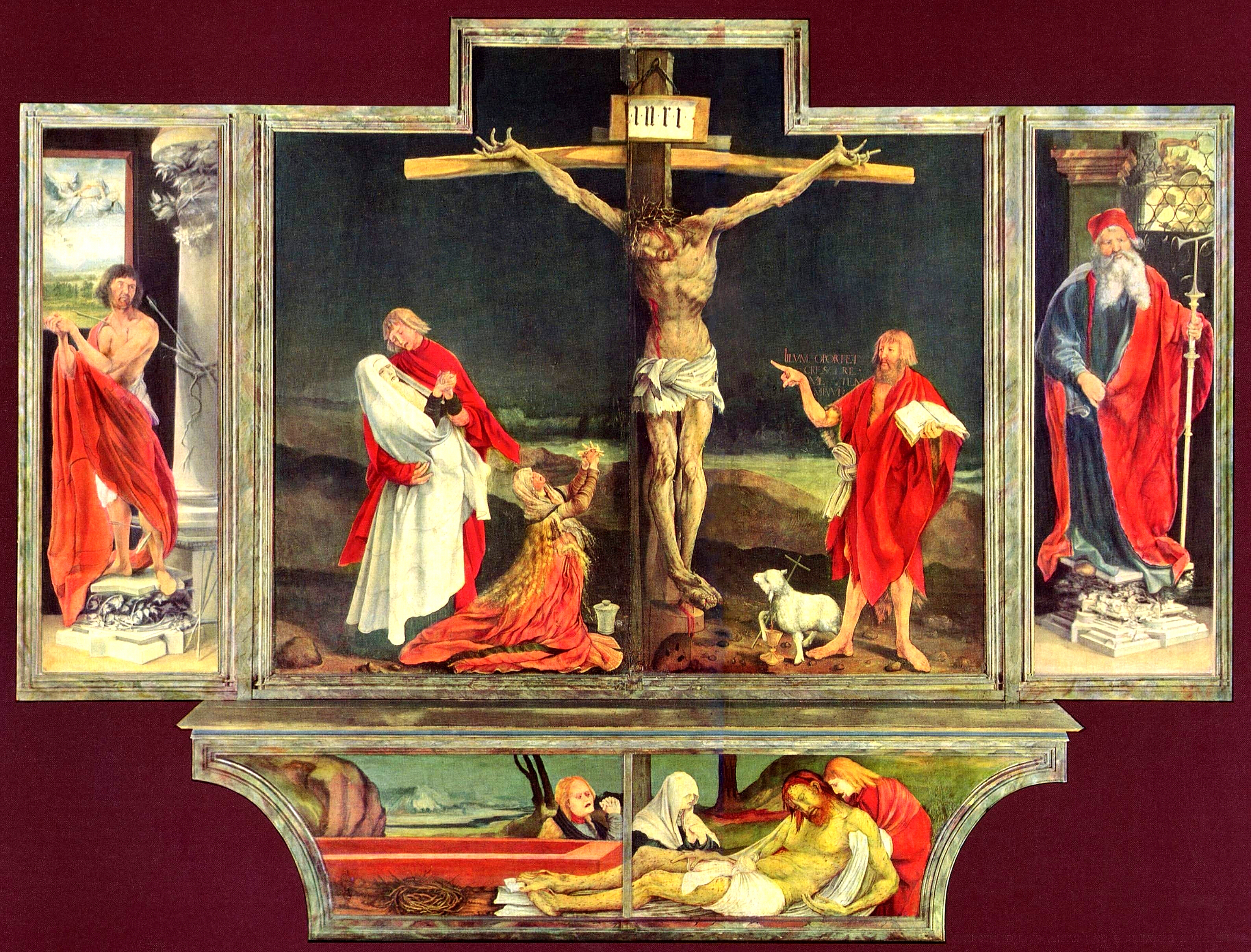

But John also, as Gruenewald’s altarpiece at Isenheim concretely proclaims, points us to Christ, and models for us in this Advent season the path to Christian maturity and to faithful witness: Illum oportet crescere, me autem minui (“He must increase; I must decrease”).

The fun I’m doing Bible study is how wonderfully varied language is in trying to describe the mystery of God.