This past Wednesday, January 29th, called Seollal in South Korea and Tet in Vietnam, marked the lunar New Year, celebrated by billions of Asiatic peoples, both in their native countries and wherever else they have found a home, worldwide. In the Chinese zodiac, this year is the Year of the Snake.

Unfortunately, for many Christian and Jewish readers, the Year of the Snake sounds ominous and threatening. Often the snake is regarded as a symbol of evil, and specifically of Satan, because of the Garden Story in Genesis 3.

The Garden Story is very well known. Much like the Twenty-third Psalm or the Ten Commandments, it has largely passed out of the hands of the church and synagogue, to become part of the cultural currency of Western, and specifically American, society. Sadly, that familiarity is likely to blind us: as we already “know” what the text says, it may take some effort to see what is actually before us.

Indeed, even those who have never read Paradise Lost are likely to assume John Milton’s plot line—a war in heaven results in the fall of Lucifer, who seduces Eve into eating the forbidden fruit, prompting Adam heroically to embrace her tragic fate—and impose that plot onto the Bible’s very different narrative.

The account of the creation of the world, and specifically of humanity, in Genesis 2:4b-25 is explicitly linked to the Garden Story by the garden itself, planted by the LORD God in Gen 2:8. The Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil in the center of Eden (Gen 2:9) is of course the centerpiece of the Garden Story; its prohibition foreshadows this story’s tragic conclusion:

The LORD God commanded the human, “Eat your fill from all of the garden’s trees; but don’t eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, because on the day you eat from it, you will die!” (Gen 2:16-17).

But another explicit link comes in the last verse of Genesis 2, and the first verse of Gen 3. The author relies on a pun to carry the point. At the conclusion of Gen 2, we are told “The two of them were naked [‘arummim], the man and his wife, but they weren’t embarrassed” (Gen 2:25). Then, in the first verse of Gen 3, we meet the snake: “The snake was the most intelligent [‘arum] of all the wild animals that the LORD God had made.”

Although spelled and pronounced very nearly the same, ‘arom (singular of the plural ‘arummim) and ‘arum come from different roots, with different meanings. The punning parallel between the nakedness of the humans and the cleverness of the snake finds its culmination in Gen 3:7. Enticed by the snaky self-confidence of the serpent, the humans eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, and “Then they both saw clearly and knew that they were naked [‘erummim].” Rather than becoming crafty (‘arum) like the serpent, they become, for the first time, shamefully aware of their nakedness (the Hebrew here is ‘erom, from which the word ‘arom in Gen 2:24 is derived).

Later tradition identifies the snake in the garden with Satan: so, Revelation 12:9 says of Satan’s endtime defeat,

So the great dragon was thrown down. The old snake [likely an allusion to Gen 3], who is called the devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world, was thrown down to the earth; and his angels were thrown down with him (see also 4 Macc 18:7-8; Wis 2:24).

But the text in Gen 3:1 explicitly describes the snake as simply a “wild animal” (Hebrew khayyat hassadeh, “beast of the field” in KJV)—the most crafty of them all, but still an animal. There is no hint here of the later notions of a war in heaven, or of Lucifer’s fall. Indeed, Christian theologian and martyr Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote, “we would be simplifying and completely distorting the biblical narrative if we were simply to involve the devil, who, as God’s enemy, caused all this. This is just what the Bible does not say” (Creation and Fall, trans. John C. Fletcher [orig. Schöpfung und Fall, Munich: Chr. Kaiser Verlag, 1937], in Creation and Temptation [London: SCM Press, 1966], 64).

In the ancient Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, the hero learns of a plant that grows at the bottom of the underworld ocean, called “As Oldster Man Becomes Child” [reminiscent of the Tree of Life in Genesis 2–3]. Eager to claim this prize, Gilgamesh dives into the ocean, weighted with stones to drag him down, down to the bottom of everything—where, sure enough, he finds the plant. He plucks it, rises to the surface, and prepares to return to his city Uruk, there to eat the plant and regain his youth. But on the journey home, Gilgamesh stops to bathe, leaving the plant unguarded. A snake swallows the plant, sheds its skin, and crawls away renewed. Deeply disappointed, but having learned that he, like all humanity, must die, Gilgamesh decides that Uruk will be his memorial; as king of that great city, his name will never be forgotten. In that way, Gilgamesh will gain immortality after all.

As the Epic of Gilgamesh illustrates, in the ancient world snakes represented new life and rebirth—doubtless due to the shedding of their skins. Therefore in Egypt, the sign of the “divine” pharaohs was the image of a rearing cobra (called the uraeus), said to have been crafted by the creator god Ptah on his potter’s wheel. Further, as Karen Joines notes, snakes were regarded in Egypt as possessors of ancient wisdom (“The Serpent in Genesis 3,” ZAW 87 [1975]: 4-5).

Little wonder then that the Garden Story describes the snake as “the most intelligent [‘arum] of all the wild animals that the LORD God had made.”” (Gen 3:1), or that Jesus urges his followers, “be wise as snakes and innocent as doves” (the same Greek words for wisdom [phronimos] and for snakes [ophios] are used in Matt 10:16 and in the Greek Septuagint text of Gen 3:1). These traditional characteristics figure in the snake’s role in Gen 3, where eating the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge leads to the loss of the Tree of Life. Any reader is bound to wonder about this prohibition, and its severe consequences. Did the Lord God really wish God’s creatures to remain in ignorance? What could the Tree of Knowledge represent, and why is its fruit forbidden?

One approach holds that what the tree signifies is irrelevant: the point is simply that the fruit of this particular tree is prohibited by God. Gregory of Nazianzus wrote,

[God gave Adam] a law as a material for his free will to act on. This law was a commandment as to what plants he might partake of and which one he might not touch. This latter was the tree of knowledge; not, however, because it was evil from the beginning when planted, nor was it forbidden because God grudged it to us—let not the enemies of God wag their tongues in that direction or imitate the serpent. But it would have been good if partaken of at the proper time (Second Oration on Easter 8).

In his novel Perelandra, C. S. Lewis reimagined the Garden Story as unfolding on a watery world in which most vegetation and animal life lived on floating islands. Here, living on the “fixed land” was the one thing forbidden by God. There was no reason given for this prohibition–the issue was simply obedience, or disobedience, to God’s word.

John Van Seters proposes that the Garden Story sets religious faith, which involves obedience to God’s commandments, over against the secular pursuit of wisdom: “wisdom was the origin and cause of humanity’s sin and fall” (Prologue to History: The Yahwist as Historian in Genesis [Louisville: Westminster/ John Knox, 1992], 125-26). Certainly, the use throughout this conversation of ‘Elohim (“God”) rather than the personal name Yhwh (“the LORD”) suggests abstract reflection rather than relationship. Bonhoeffer calls this “the first conversation about God, the first religious, theological conversation. It is not prayer or calling upon God together but speaking about God” (Bonhoeffer 1966, 69). Yet faith is surely more than rule-following, and in our Bible, the pursuit of wisdom is grounded in faith: “Fear of the Lord is where wisdom begins” (Psalm 111:10; see also Prov 1:7; 2:5-6; Job 28:28).

Others have proposed that eating the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil means learning the difference between good and evil, and so gaining freedom of choice. Before, the humans could only do what God wanted them to do. Now, having eaten the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, they have the capacity to make their own choices, which inevitably leads to their making wrong ones. So, Augustine wrote, “‘The eyes of them both were opened,’ not to see, for already they saw, but to discern between the good they had lost and the evil into which they had fallen” (City of God, 14.17). Jacqueline Lapsley suggests,

In short, eating from the tree enables one to become an interpreter—a moral interpreter—of one’s world. This is what it means to ‘become like God/gods, knowing good and bad’ (3:5; cf. 3:22). This, in the end, will be what distinguishes the human couple from the animals (Whispering the Word: Hearing Women’s Stories in the Old Testament [Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2005], 15).

In the story as it unfolds in Genesis, however, there is no inkling that God had previously deprived God’s creations of freedom. The woman’s choice to eat the fruit, as Phyllis Trible observes, demonstrates careful reflection and independent thought:

She contemplates the tree, taking into account all the possibilities. The tree is good for food; it satisfies the physical drives. It pleases the eyes; it is esthetically and emotionally desirable. Above all, it is coveted as the source of wisdom. . . Thus the woman is fully aware when she acts, her vision encompassing the gamut of life (Trible 1979, 79).

Eating from the tree does not convey these discriminating capacities: the Woman clearly has them already. Indeed, since both the Man and the Woman choose to eat from the Tree of Knowledge, they are plainly able to make moral choices even before eating this fruit.

That the freedom to choose, and so the potential for disobedience, is given to human being from the first is expressed in Bereshit Rabbah 14. The rabbis observe that in Gen 2:7, where the Lord God creates ha’adam, the word for “formed” is spelled oddly, with an extra yod (wayyiytser). From this doubling, they conclude that there must have been two formations. R. Hanina bar Idi says that the duality is bound up within ha’adam: God has created them, from the first, with “two formations, a good formation and an evil formation” (BerRab 14.4, Jacob Neusner translates this as “both the impulse to do good and the impulse to do evil”).

Perhaps the best way to understand the expression “the Knowledge of Good and Evil” is as a merism, like “young and old” or “length and breadth,” referring not just to the two opposite terms mentioned, but to the entire range between them. This would imply that eating the fruit would convey a godlike knowledge of everything from good to evil. That is in fact what the snake promises: “you will be like ‘elohim [gods/God]” (Gen 3:5). Indeed, after the man and woman have eaten the fruit, the LORD addresses the heavenly council:

The LORD God said, “The human being has now become like one of us, knowing good and evil.” Now, so he doesn’t stretch out his hand and take also from the tree of life and eat and live forever, the LORD God sent him out of the garden of Eden to farm the fertile land from which he was taken (Gen 3:22-23).

Reading canonically, these references to the humans becoming “like God” are bound to recall to our minds the statement in the first creation account that woman and man are created in God’s image (Gen 1:26-27)–an idea not expressed in this second account, in which “Godlikeness” is a temptation and a problem rather than a promise. But for the reader encountering these chapters together in their context in Genesis, the connection produces a magnificent irony, not apparent when reading the passages separately.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/wizard-of-oz1-b3190fbf82ac4ccb92639ee98d8b9e8b.jpg)

In L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz, the characters all seek from the Wizard qualities that we know, from the story, they already possess: the “brainless” Scarecrow does all the planning; the “cowardly” Lion courageously defends Dorothy and his friends from their enemies, and no one could possibly be more tender-hearted than the “heartless” Tin Woodsman! Just so, in the final, canonical form of these chapters in Genesis, the Woman and the Man want what they already have: to be like God. But they do not realize this, and so through disobedience lose the Garden and all that it represents, including the Tree of Life.

To return to the snake: why, if the serpent in Genesis 3 is simply a snake, are the snakes we know so different? Described when we first encounter it as the most intelligent of all wild animals (Gen 3:1), the snake now becomes the most cursed: set lower than all other animals, wild or domesticated (Gen 3:14). The curse on the snake comes in two parts. First, it loses its limbs, and its ability to speak:

Because you did this,

you are the one cursed [Hebrew ‘arur]

out of all the farm animals,

out of all the wild animals.

On your belly you will crawl,

and dust you will eat

every day of your life (Gen 3:14).

Why don’t snakes have legs? Why do they crawl on their bellies? Why do they keep sticking out their tongues and licking the ground? The short answer, in this ancient story, is that snakes are cursed. Because of their involvement in humanity’s disobedience, they must crawl on the ground and continually lick the dust–which is also why snakes can no longer talk.

The second aspect of the curse turns to another etiological feature of this narrative: why do snakes bite? Why are they poisonous? Why do we hate and fear them? The Lord God declares,

I will put contempt

between you and the woman,

between your offspring and hers.

They will strike your head,

but you will strike at their heels (Gen 3:15).

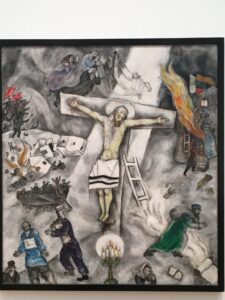

Some traditional Christian interpreters (Irenaus, Against Heresies 5.21.1; Martin Luther, Lectures on Genesis, 3.4.5) regarded Genesis 3:15 as a prediction of the coming of Christ: the Devil would strike at his heel, wounding him on the cross, but Christ would rise from the dead, and at his return crush the enemy’s head . But as John Calvin observed in his commentary on this passage,

Some traditional Christian interpreters (Irenaus, Against Heresies 5.21.1; Martin Luther, Lectures on Genesis, 3.4.5) regarded Genesis 3:15 as a prediction of the coming of Christ: the Devil would strike at his heel, wounding him on the cross, but Christ would rise from the dead, and at his return crush the enemy’s head . But as John Calvin observed in his commentary on this passage,

Gladly would I give my suffrage in support of their opinion, but that I regard the word seed as too violently distorted by them; for who will concede that a collective noun is to be understood of one man only? Further, as the perpetuity of the contest is noted, so victory is promised to the human race through a continual succession of ages. I explain, therefore, the seed to mean the posterity of the woman generally (Comm Gen 3:15).

Calvin realized therefore that this passage was not about Satan and Christ, but about snakes and people:

I interpret this simply to mean that there should always be the hostile strife between the human race and serpents, which is now apparent; for, by a secret feeling of nature, man abhors them (Comm Gen 3:15).

Calvin’s insistence upon close attention to the Hebrew, and to the contextual, historical interpretation of texts, put him at odds with many of his contemporaries. However, his stubborn insistence on staying with the text remains a fine example for our reading of Scripture.

What is the consequence of eating the fruit for the humans? The Garden Story says,

the Lord God sent him out of the garden of Eden to farm the fertile land from which he was taken. He drove out the human. To the east of the garden of Eden, he stationed winged creatures wielding flaming swords to guard the way to the tree of life (Gen 3:23).

Without access to the fruit of the Tree of Life, women and men will now die–just as God had said they would, should they eat from the forbidden Tree of Knowledge. Leaving the garden of Eden behind, the Woman and the Man now enter a world like the world that we know, where life can be brutal and hard, where pain and suffering are sad realities, and where all of us must, sooner or later, die.

But unlike the snake, the Woman and the Man are not cursed: the word ‘arur is not used for them! The snake is cursed, even the ground is cursed, but they are not. Indeed, God cares for them, covering their nakedness with garments God makes from the skins of animals (Gen 3:21). In the end, this story is about God’s desire to be in relationship with us even when we spurn that relationship. We are not cursed, spurned, or rejected by God, even though the consequences of our actions wound our world and one another.

Genesis 3 is not science. Herpetologists are happy to explain to us that snakes sense the presence of prey or enemies in large part by “tasting” the air and the ground–that is why they stick out their tongues. They will also assure us of the importance of snakes as predators in the ecosystem. In the story world of Genesis 3, the “snakiness” of snakes is the consequence they suffer for their role in the humans’ disobedience. But while we should be respectful of any wild animal, most snakes are neither venomous nor aggressive. We need neither hate nor fear them–especially in this Year of the Snake.

.svg/2000px-Great_Seal_of_the_United_States_(obverse).svg.png)

![Title: In the Beginning [Click for larger image view]](https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/creation32fudhj5498.jpg)

On May 2, President Donald Trump signed

On May 2, President Donald Trump signed

Most of the people we meet in the Bible are grownups. Adam and Eve may be brand new when we are introduced, but they are born full grown! Likewise, we meet Abraham as an adult, and Paul, and Peter. In the Gospels of

Most of the people we meet in the Bible are grownups. Adam and Eve may be brand new when we are introduced, but they are born full grown! Likewise, we meet Abraham as an adult, and Paul, and Peter. In the Gospels of

![Title: Disputation with the Doctors [Click for larger image view]](https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/Duccio_di_Buoninsegna_Disputation_with_the_Doctors.jpg) After three days (three days!) Mary and Joseph find their son in the temple, in an intense conversation with the religious leaders. We learn that even as a boy, Jesus has attained a terrifying sense of his identity and calling: “I must be in my Father’s house” (

After three days (three days!) Mary and Joseph find their son in the temple, in an intense conversation with the religious leaders. We learn that even as a boy, Jesus has attained a terrifying sense of his identity and calling: “I must be in my Father’s house” (

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/wizard-of-oz1-b3190fbf82ac4ccb92639ee98d8b9e8b.jpg)

Some traditional Christian interpreters (Irenaus, Against Heresies 5.21.1; Martin Luther, Lectures on Genesis, 3.4.5) regarded Genesis 3:15 as a prediction of the coming of Christ: the Devil would strike at his heel, wounding him on the cross, but Christ would rise from the dead, and at his return crush the enemy’s head . But as John Calvin observed in his

Some traditional Christian interpreters (Irenaus, Against Heresies 5.21.1; Martin Luther, Lectures on Genesis, 3.4.5) regarded Genesis 3:15 as a prediction of the coming of Christ: the Devil would strike at his heel, wounding him on the cross, but Christ would rise from the dead, and at his return crush the enemy’s head . But as John Calvin observed in his