Once again (it happened in 2018, too, remember!) Ash Wednesday falls on Valentines Day. Certainly the contrast– the sweetest and most sentimental of secular holidays juxtaposed with the grimmest and most lugubrious of Christian fast days–is striking, and may prompt us to wonder why the church should be such a downer–so determined, it seems, to quash anything fun.

The Old Testament reading for Ash Wednesday, Joel 2:1-2, 12-17, certainly seems to fit that killjoy perception:

Blow the trumpet in Zion; sound the alarm on my holy mountain! Let all the inhabitants of the land tremble, for the day of the LORD is coming, it is near—a day of darkness and gloom, a day of clouds and thick darkness! (Joel 2:1-2).

Then again, the relentless glee of what my colleague Andrew Purves scornfully termed “happy clappy worship” can be no less oppressive and unwelcoming! I still remember a courageous sermon preached in the PTS chapel, observing that our community was a very hard place to be if you were sad. People who were hurting or depressed were likely either to be ignored, or worse, to be jollied: to be told to cheer up and trust in Jesus—as though sorrow and pain were somehow a denial of their faith.

As Donald Gowan ruefully observes,

Christian worship tends to be all triumph, all good news (even the confession of sin is not a very awesome experience because we know the assurance of pardon is coming; it’s printed in the bulletin). And what does that say to those who, at the moment, know nothing of triumph?” (Don Gowan, The Triumph of Faith in Habakkuk [Atlanta: John Knox, 1976], 38).

But true repentance leading to new life requires lament: not only our own authentic lament at the realization of our sin, but also providing space for, and attending to, the laments of others.

Walter Brueggemann writes that the loss of lament in worship means “the loss of genuine covenant interaction because the second party to the covenant (the petitioner) has become voiceless or has a voice that is permitted to speak only praise and doxology” (Walter Brueggemann, “The Costly Loss of Lament,” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 36 [1986]: 60).

No wonder Joel urges the priests, “Gather the elders and all the inhabitants of the land to the house of the LORD your God, and cry out to the LORD” (Joel 1:14). By stifling lament, we shut off the genuine interaction that a living relationship with God presumes.

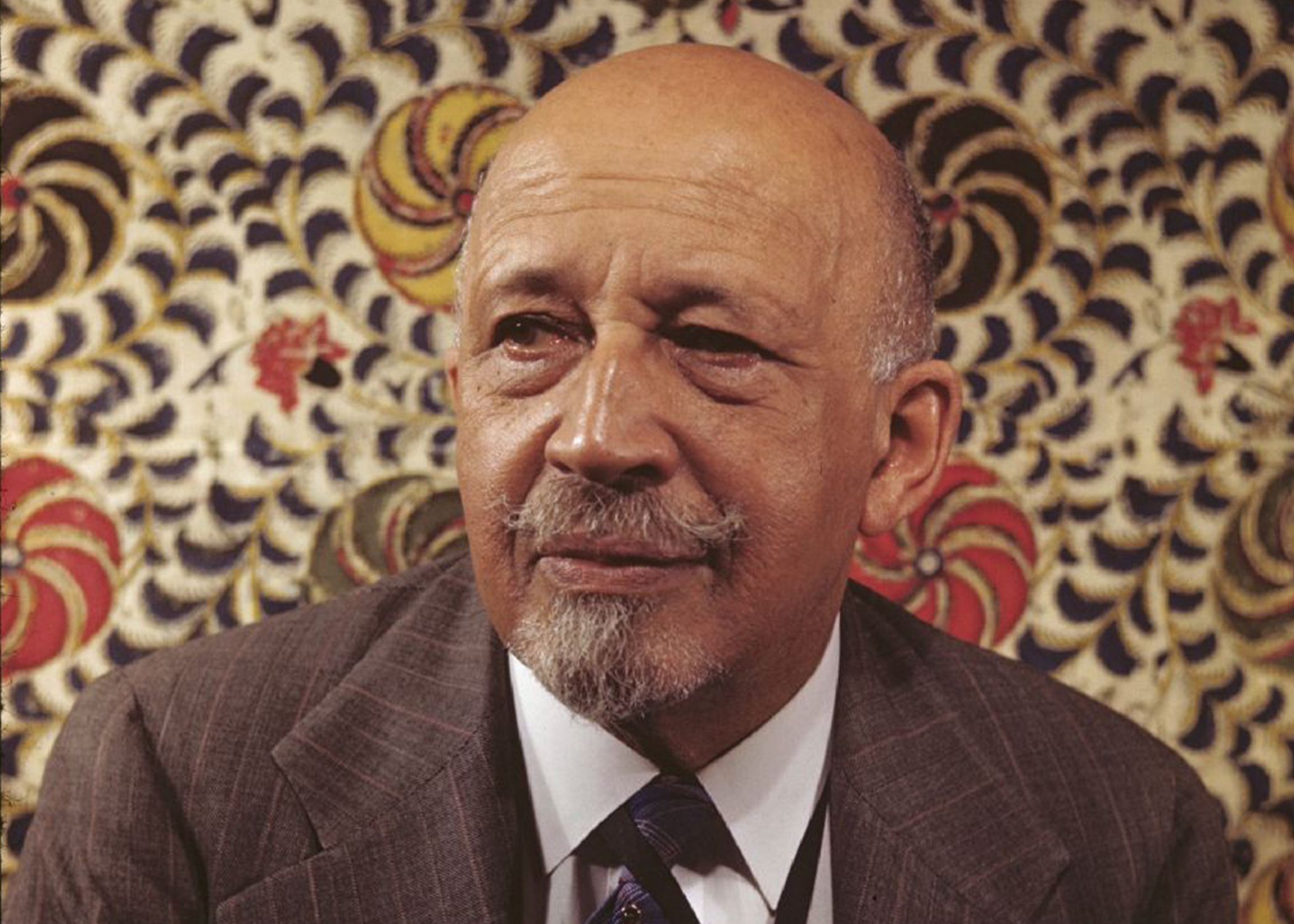

In his famous lament, the “Letter From a Birmingham Jail,” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. told “my Christian and Jewish brothers”

I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate . . . who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice. . . Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

Of course we prefer the easy road that avoids confrontation, the “negative peace which is the absence of tension.” But for Joel as for Dr. King, true peace doesn’t come so easily!

Yet even now, says the LORD, return to me with all your heart, with fasting, with weeping, and with mourning; rend your hearts and not your clothing (Joel 2:12-13).

Joel calls upon his community to demonstrate their whole-hearted desire to return to the Lord, and their deep sorrow at past wrong-doing, “with fasting, with weeping, with mourning.” This can be no superficial demonstration: “rend your heart,” the LORD demands, “and not your clothing.”

The setting for much of Joel’s remarkable book of prophecy is a locust plague, which has decimated Judah. After the swarm has passed, when the locusts all are gone, reassurance is offered to the community, the “children of Zion” (Joel 2:23), who twice are promised, “my people shall never again be put to shame” (Joel 2:26, 27).

But the people also learn that they are part of a larger community than they had known.

After that I will pour out my spirit upon everyone;

your sons and your daughters will prophesy,

your old men will dream dreams,

and your young men will see visions.

In those days, I will also pour out my

spirit on the male and female slaves.

I will give signs in the heavens and on the earth—blood and fire and columns of smoke (Joel 2:28-30).

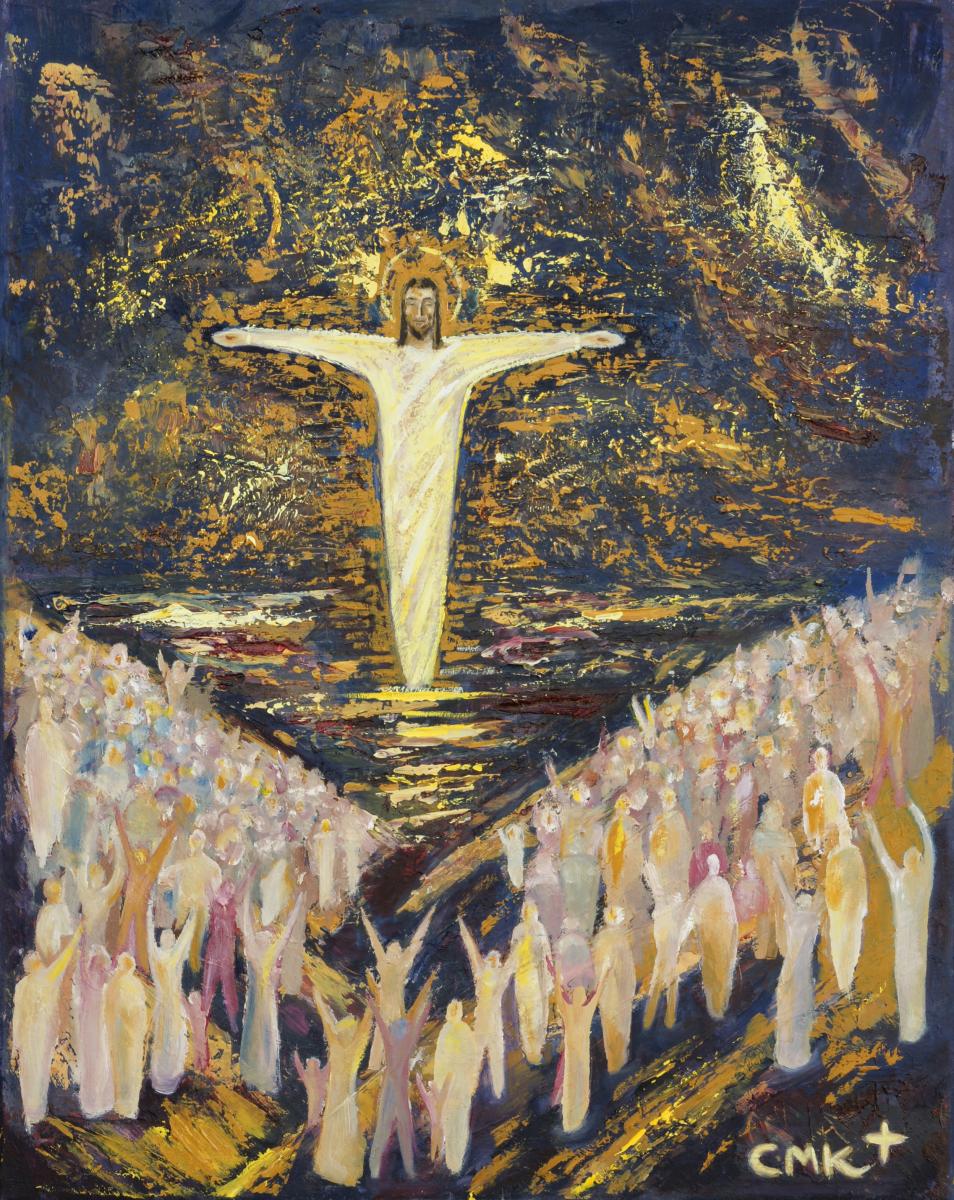

In this passage—the most familiar passage from this book, quoted by Peter in his sermon at Pentecost (Acts 2:17-21)—the “children of Zion,” called “my people” by the Lord, include not just the adult men of the worshipping congregation, but women, children, the aged—even slaves.

Joel reminds us that we too belong to a larger community than we had known. We may have forgotten that—I confess that often I have forgotten that. We succumb to the temptation to define our community too narrowly, as including only those like us, whether ethnically or ideologically or theologically.

May this Valentines Day/Ash Wednesday, and the days of Lent that follow, reawaken us to our connections to one another. May we give one another space to lament, to grieve, to disagree. May we begin to listen to one another—not necessarily to agree, but to listen, to learn, and to understand. God’s promises of deliverance, of vindication, of freedom from shame cannot be experienced by us separately and severally. They are not offered to us in that way. We will find them together—all of us—or we will not find them at all.

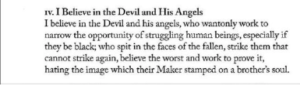

I learned of this piece through a concert at my home church, St. Paul’s UMC, by Archipelago, an extraordinary vocal ensemble conducted by Caron Daley of Duquesne University. The climax of the evening was a wonderful choral setting of DuBois’ “Credo” by African American composer

I learned of this piece through a concert at my home church, St. Paul’s UMC, by Archipelago, an extraordinary vocal ensemble conducted by Caron Daley of Duquesne University. The climax of the evening was a wonderful choral setting of DuBois’ “Credo” by African American composer

This day, in the dead of winter, is associated with hope for the return of warmer weather–but not too soon. A “false spring” after all may be followed by a killing frost, wiping out trees that have budded too early, and threatening lambs born out of season. Therefore, sunny weather on this midwinter day (so that a groundhog can see its shadow!) is held to be a bad omen of more bleak days ahead, while cold and cloudy weather appropriate to the season augurs the swift return of sunshine and greenery.

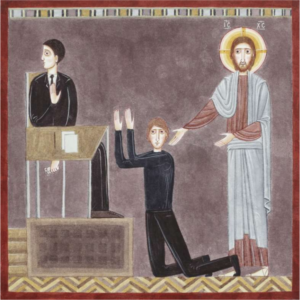

This day, in the dead of winter, is associated with hope for the return of warmer weather–but not too soon. A “false spring” after all may be followed by a killing frost, wiping out trees that have budded too early, and threatening lambs born out of season. Therefore, sunny weather on this midwinter day (so that a groundhog can see its shadow!) is held to be a bad omen of more bleak days ahead, while cold and cloudy weather appropriate to the season augurs the swift return of sunshine and greenery.![Title: Presentation in the Temple [Click for larger image view]](http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/C_FirstSundayafterChristmas.jpg) This tapestry depicting Luke’s scene is from the Abbey Church of St. Walpurga in Virginia Dale, Colorado. The Order of St. Walpurga was established in the 11th century in Bavaria. The nuns of that order fled to the United States in 1935 to escape the Nazis, and settled in the Colorado mountains. The walls of their church are lined with tapestries like this one of the Presentation of the Lord, all inspired by biblical texts.

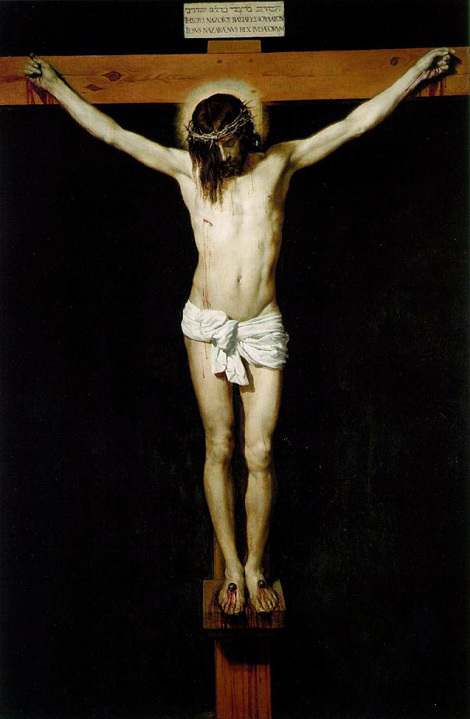

This tapestry depicting Luke’s scene is from the Abbey Church of St. Walpurga in Virginia Dale, Colorado. The Order of St. Walpurga was established in the 11th century in Bavaria. The nuns of that order fled to the United States in 1935 to escape the Nazis, and settled in the Colorado mountains. The walls of their church are lined with tapestries like this one of the Presentation of the Lord, all inspired by biblical texts. Although Jesus has come for everyone, not everyone will receive him. Simeon’s words prefigure Jesus’ coming rejection–his trial, condemnation, and crucifixion, and so Mary’s coming sorrow: “And a sword will pierce your innermost being too” (Luke 2:35). In this season after Epiphany, we rightly remember that Jesus’ way leads us to God’s light–but that way must pass through the darkness of the cross. Simeon offers no illusions that God’s salvation comes easily, without opposition or conflict.

Although Jesus has come for everyone, not everyone will receive him. Simeon’s words prefigure Jesus’ coming rejection–his trial, condemnation, and crucifixion, and so Mary’s coming sorrow: “And a sword will pierce your innermost being too” (Luke 2:35). In this season after Epiphany, we rightly remember that Jesus’ way leads us to God’s light–but that way must pass through the darkness of the cross. Simeon offers no illusions that God’s salvation comes easily, without opposition or conflict.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-1127577455-af4de78e939a40d9b37032ef9e24fd8a.jpg)

![Title: Silence [Click for larger image view]](https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/silencenmh9h5b8g7y7gh201.jpg) In the alternate Hebrew Bible reading for this Sunday (

In the alternate Hebrew Bible reading for this Sunday (

Here we go again! The Jack o’ lanterns, spooks, giant skeletons, and other holiday decorations in lawns and department store windows, the heaps of candy in grocery stores, the perennial return of pumpkin-spice-EVERYTHING–after Christmas, “Halloween” is the biggest commercial holiday of the year. But what many will not realize is that, like Christmas, Hallowe’en is properly a Christian celebration.

Here we go again! The Jack o’ lanterns, spooks, giant skeletons, and other holiday decorations in lawns and department store windows, the heaps of candy in grocery stores, the perennial return of pumpkin-spice-EVERYTHING–after Christmas, “Halloween” is the biggest commercial holiday of the year. But what many will not realize is that, like Christmas, Hallowe’en is properly a Christian celebration. Because of its association with Samhain,

Because of its association with Samhain,

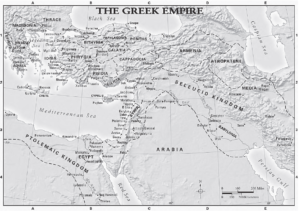

Justice and vengeance have been on all our minds this month. On October 7, terrorists from the militant organization Hamas (the ruling political faction in Gaza) swept out of the Gaza Strip as far as 15 miles into Israel, attacking 22 farms, towns, and other communities; 1,400 Israelis were killed and 200 were taken hostage. More Jews were killed and wounded in this attack than on any other single day since the Nazi Holocaust.

Justice and vengeance have been on all our minds this month. On October 7, terrorists from the militant organization Hamas (the ruling political faction in Gaza) swept out of the Gaza Strip as far as 15 miles into Israel, attacking 22 farms, towns, and other communities; 1,400 Israelis were killed and 200 were taken hostage. More Jews were killed and wounded in this attack than on any other single day since the Nazi Holocaust.