.svg/2000px-Great_Seal_of_the_United_States_(obverse).svg.png)

This Friday, July 4th, is of course Independence Day—the 249th birthday of our nation. The Great Seal of the United States, depicted above, is emblazoned with the Latin motto, E Pluribus Unum. This Latin phrase was adopted by an Act of Congress in 1782 as the motto for the Seal, and it has been used on our currency since 1795.

“E [an abbreviation for ex] pluribus unum” means “out of many, one.” It was suggested as a motto by Pierre Eugene du Simitierre, one of the designers working on the seal. While the Founders didn’t go with his design (which is rather fiddly!), they liked his motto!

Apparently, du Simitierre got the motto from the title page of The Gentleman’s Magazine, a popular magazine of the day that (rather like Reader’s Digest) took its content from a number of places. But where did the editors of this magazine find it? Some think the Latin phrase came originally from a line in “Moretum,” a poem attributed to Virgil, which describes grinding together many ingredients to make a cheese spread:

Till by degrees they one by one do lose

Their proper powers, and out of many comes

A single colour [color est e pluribus unus]

A more dignified proposal is that the phrase was adapted from Cicero’s De Officiis (“Concerning Duties”) 1.17.56, regarding friendship:

When each person loves the other as much as himself, it makes one out of many [unus fiat ex pluribus], as Pythagoras wishes things to be in friendship.

But whatever the original source, we can see why du Simitierre proposed this motto, and why the Founders liked it. It well describes the United States of America, as many states unified into a single nation.

However, while E Pluribus Unum graces our currency and our Great Seal, it is not our national motto. That would be “In God We Trust”–approved by our Legislature and signed into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on July 30, 1956 (the year I was born). That same law also stipulated that this motto, which had already been placed on some coins since 1864, be printed on all currency issued after that date.

Having two mottoes only becomes a problem if we see a conflict between them. Does diversity threaten our trust in God? Some may think that it does: that real Americans (or real Christians) must look like me, or at least, think and act like me, and that the borders between those inside and those outside must be clearly marked and defended.

Already in these first months of the Trump administration, masked ICE agents have been seizing immigrants–or those they suspect to be immigrants–off the street, out of workplaces, and even in courtrooms where those seized were in the process of pursuing legal residence. The images above come from a three minute video clip, filmed by Pastor Ara Torosian, an Iran-born pastor at Cornerstone Church West LA, as two members of his congregation, Iranian Christian asylum-seekers, were arrested by masked federal agents:

The pastor told the agents the husband was an asylum-seeker as they carried out the arrest, to which one responded, ‘It doesn’t matter, sir, we’re just following orders, he’s got a warrant,’ according to the video footage. . . . both individuals are now in the custody of Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Enforcement and Removal Operations, according to the CBP statement.

Pastor Torosian “said the scene shocked him and reminded him of his home country, which he fled in 2010.”

“Seeing this masked man on the floor, with this woman, I got triggered. I said, ‘Where am I?’ in one moment. I said, ‘Where I am, in the street of Tehran or the street of Los Angeles?’”

Roman Catholic bishops across the United States have begun objecting to this treatment of migrants, including Christians fleeing persecution, and challenging the president’s policy.

For years many bishops focused their most vocal political engagement on ending abortion, rarely putting as much capital behind any other issue. Many supported President Trump’s actions to overturn Roe v. Wade, and targeted Democratic Catholic politicians who supported abortion access.

But now they are increasingly invoking Pope Leo XIV’s leadership and Pope Francis’s legacy against Mr. Trump’s immigration actions, and prioritizing humane treatment of immigrants as a top public issue. They are protesting the president’s current domestic policy bill in Congress, showing up at court hearings to deter Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents, and urging Catholics and non-Catholics alike to put compassion for humans ahead of political allegiances.

The image in Los Angeles and elsewhere of ICE agents seizing people in Costco parking lots and carwashes “rips the illusion that’s being portrayed, that this is an effort which is focused on those who have committed significant crimes,” said Cardinal Robert W. McElroy of Washington, in an interview from Rome.

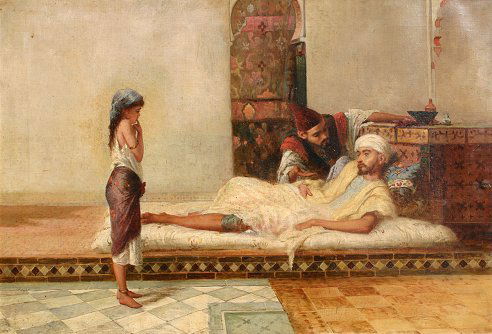

This brings us to the Hebrew Bible reading for Sunday: the healing of Naaman the leper, in 2 Kings 5:1-14. In this passage, Naaman is the ultimate outsider. Not only is he a Gentile (a non-Israelite), he comes from Aram, or Syria—in those days, Israel’s sworn enemy. Further, not only is he a Syrian, he is a soldier in Syria’s army, and not only a soldier, but a general—one of Israel’s oppressors!

Believe it or not, it gets worse: Naaman finds about about the wonder-working prophet Elisha from a Hebrew slave, a young girl stolen from her home and family in one of Syria’s raids (2 Kgs 5:2-3)! Adding insult to injury, Naaman then tries to deal his way to a healing, through political pressure (my king writing to your king) and bribery (2 Kgs 5:5-7).

Naaman’s healing comes in a way that makes abundantly clear that it is God, not Elisha, who does the healing. Elisha never even sees Naaman! Through his servant, he commands the Syrian general to immerse himself in the Jordan seven times. In his snobbery, Naaman is on the point of refusing to do what the prophet commands:

Aren’t the rivers in Damascus, the Abana and the Pharpar, better than all Israel’s waters? Couldn’t I wash in them and get clean?” So he turned away and proceeded to leave in anger (2 Kgs 5:12).

Yet, despite all of this, Naaman is persuaded to do as the prophet directed: and he is healed, anyway. Moreover, even though he misunderstands who God is (Naaman takes “two mule loads” of dirt from Israel so as to worship Israel’s God, as though the LORD were somehow tied to Israel’s soil) and what commitment to God means (the Syrian general continues to go to Rimmon’s temple, for political expediency; see 2 Kgs 5:17-18), God does not take the healing back! Indeed, if we read closely, God’s presence and involvement with Naaman began long before he ever came to see Elisha: “through him the LORD had given victory to Aram” (2 Kgs 5:1).

In Luke’s gospel, Jesus retells Naaman’s story for exactly this reason—to show that God is at work even among those unlike us, whom we see as outsiders. The response of Jesus’ hometown crowd in Nazareth shows how popular that sermon was–they try to throw him off a cliff!

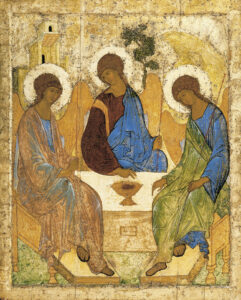

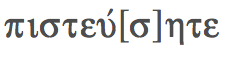

In the Gospel reading for Sunday (Luke 10:1-11, 16-20 RSV and NRSV), Jesus sends out seventy (or, as the CEB and NRSVue read with other ancient texts, “seventy-two”) followers: that is six, the number of humanity, times twelve, the number of Israel. Traditionally, this was the number of the foreign nations, based on the Table of Nations in Genesis 10. The theme, again, is a call to outreach and inclusion for all the world.

It is not that we insiders, who have Christ as our possession, take him with us to those outside. It is, rather that we go to find him among the outsiders, where Christ already is: with foreigners and lepers and clueless, unclean folk like Naaman.

After the slaughter of 49 LGBTQ people, mostly Latinos and Latinas, in Orlando in 2016, Lutheran pastor and emergent church leader Nadia Bolz-Weber preached a message that resonates powerfully still today–and reminds us why this unseemly grace is such good news:

I mean, I may want a vigilante saviour. But what I need is a saviour who brings a swift, terrible mercy. What I want is a dividing saviour – who will draw the same lines I would draw…but what I need is a saviour who makes us one, a saviour, who lifted up, draws all people to himself. Not just the worthy. Not just the lovely, the likely and the lucky. All people. I need a saviour who commands me to love my enemies and pray for those who persecute me – pray for those whose hate blinds them to their own goodness and the worth and dignity of others. And I need a saviour this merciful because it is I who needs this much mercy.

This, in the end, is the reason that for those who believe, “In God We Trust” belongs inextricably with E Pluribus Unum. Those who trust in God know that making one out of many is God’s design and delight:

This is what God planned for the climax of all times: to bring all things together in Christ, the things in heaven along with the things on earth (Ephesians 1:10).

![Title: In the Beginning [Click for larger image view]](https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/creation32fudhj5498.jpg)

On May 2, President Donald Trump signed

On May 2, President Donald Trump signed

Most of the people we meet in the Bible are grownups. Adam and Eve may be brand new when we are introduced, but they are born full grown! Likewise, we meet Abraham as an adult, and Paul, and Peter. In the Gospels of

Most of the people we meet in the Bible are grownups. Adam and Eve may be brand new when we are introduced, but they are born full grown! Likewise, we meet Abraham as an adult, and Paul, and Peter. In the Gospels of

![Title: Disputation with the Doctors [Click for larger image view]](https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/Duccio_di_Buoninsegna_Disputation_with_the_Doctors.jpg) After three days (three days!) Mary and Joseph find their son in the temple, in an intense conversation with the religious leaders. We learn that even as a boy, Jesus has attained a terrifying sense of his identity and calling: “I must be in my Father’s house” (

After three days (three days!) Mary and Joseph find their son in the temple, in an intense conversation with the religious leaders. We learn that even as a boy, Jesus has attained a terrifying sense of his identity and calling: “I must be in my Father’s house” (

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/wizard-of-oz1-b3190fbf82ac4ccb92639ee98d8b9e8b.jpg)

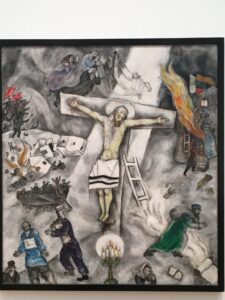

Some traditional Christian interpreters (Irenaus, Against Heresies 5.21.1; Martin Luther, Lectures on Genesis, 3.4.5) regarded Genesis 3:15 as a prediction of the coming of Christ: the Devil would strike at his heel, wounding him on the cross, but Christ would rise from the dead, and at his return crush the enemy’s head . But as John Calvin observed in his

Some traditional Christian interpreters (Irenaus, Against Heresies 5.21.1; Martin Luther, Lectures on Genesis, 3.4.5) regarded Genesis 3:15 as a prediction of the coming of Christ: the Devil would strike at his heel, wounding him on the cross, but Christ would rise from the dead, and at his return crush the enemy’s head . But as John Calvin observed in his