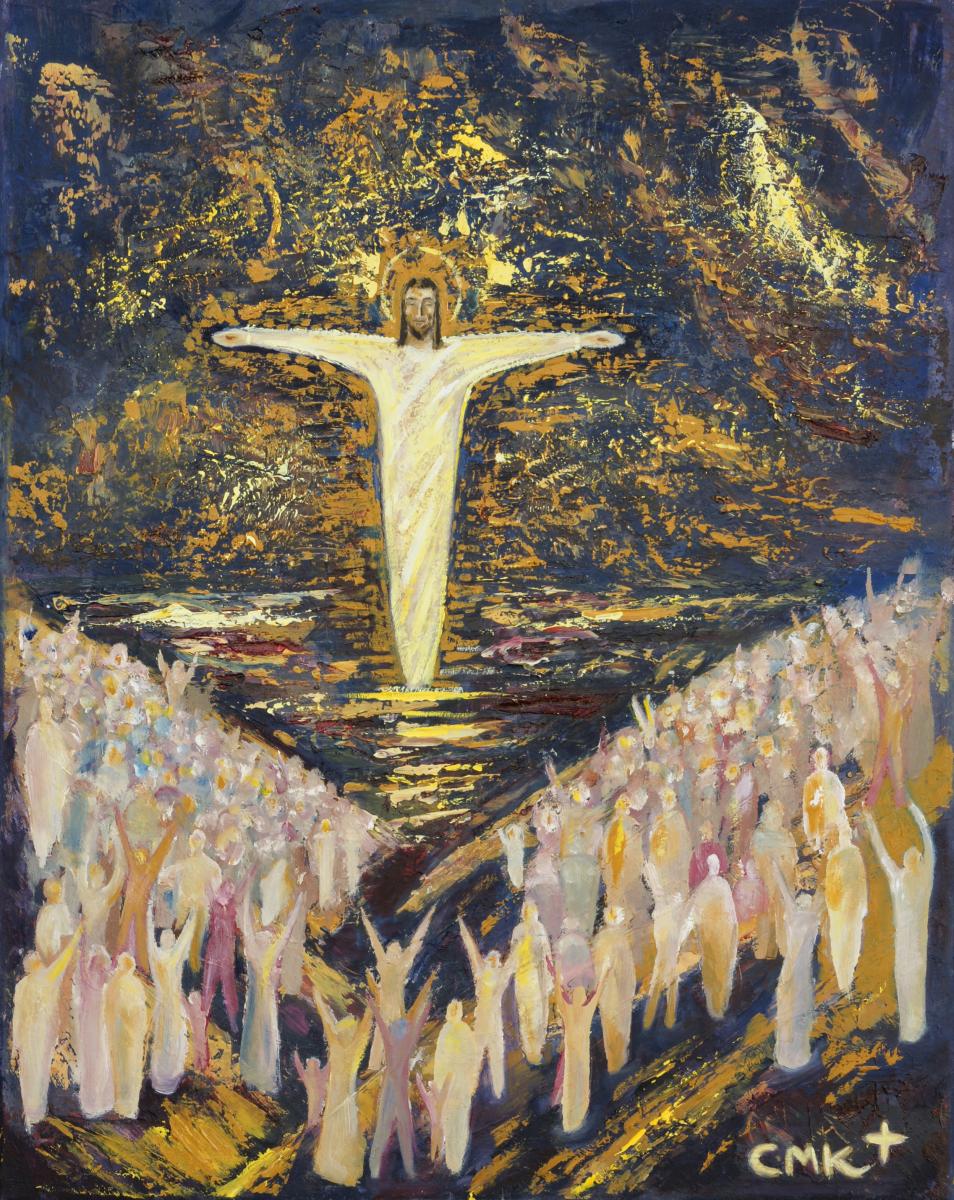

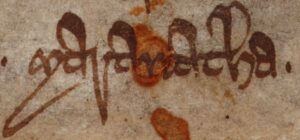

This Sunday is the first of the four Sundays in Advent, the season of the Christian year devoted to anticipating the coming of Christ–both Jesus’ birth, celebrated on Christmas Day, and his promised return at the end of the age. For some time, I have used the ancient Christian salutation Maranatha (here, from the medieval Southwick Codex) in this season as a benediction, after prayers, and to close emails. So, where does it come from and what does it mean?

In the King James Bible, the concluding verses of Paul’s first letter to the church at Corinth read:

The salutation of me Paul with mine own hand. If any man love not the Lord Jesus Christ, let him be Anathema Maranatha. The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ be with you. My love be with you all in Christ Jesus. Amen (1 Cor 16:21-24).

King James’ translators followed the Latin Vulgate in leaving those two enigmatic words in 1 Corinthians 16:22 untranslated, but few modern translators have done so. The Common English Bible is typical: “A curse on anyone who doesn’t love the Lord. Come, Lord!”

The first of the two, the Greek anathema, does mean “curse.” This word appears six times in the New Testament. In Acts 23:14, Paul’s enemies swear an oath not to eat until they have killed the apostle, calling a curse upon themselves if they fail. The other five uses of anathema are all in Paul’s letters (Rom 9:3; 1 Cor 12:3, 16:22; Gal 1:8-9). The Vulgate carries the word over untranslated in all five passages, although the KJV follows suit only once, in 1 Cor 16:22.

In the Greek Septuagint, anathema is used 25 times for the difficult expression kherem (or “the ban”) in the Hebrew Bible (for example, Lev 27:28; Num 21:3; Deut 13:15, 17 [13:16-18 in Hebrew]). This word, sometimes also rendered “curse” (see Malachi 4:6 [Hebrew 3:24]) is often connected with holy war, where the enemy is utterly destroyed as a kind of whole offering to God. But this cannot be the intention of kherem everywhere that the term appears. For example, Deuteronomy 7:2 orders that the inhabitants of the land be hakharem takharim, that is, “certainly (or completely) placed under the ban” (the NRSVue reads “you must utterly destroy them”). Yet the very next verse forbids intermarriage—difficult to understand if the intent of the text is genocide (see Jerome Creach, Violence in Scripture [Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2013], 108)! Drawing on Origen’s allegorical reading of the ban as depicting the believer’s spiritual struggle with sin (“within us are the Canaanites; within us are the Perizzites; here [within] are the Jebusites,” Homilies on Joshua, 34; cited by Creach, 102), Jerome Creach suggests that kherem came to be sublimated or spiritualized, so that what had once been a “reprehensible practice . . . close to ‘ethnic cleansing,’ was transformed into a metaphor of spiritual purity” (Creach, 108).

In church history, anathema took on a quite specific meaning:

In AD 431 St. Cyril of Alexandria pronounced his 12 anathemas against the heretic Nestorius. In the 6th century anathema came to mean the severest form of excommunication that formally separated a heretic completely from the Christian church and condemned his doctrines; minor excommunications, while prohibiting free reception of the sacraments, obliged (and permitted) the sinner to rectify his sinful state through the sacrament of penance.

Whether Paul intended anathema in this formal (and radical) sense is debatable (and I would say, doubtful). But likely, this is the reason that the Vulgate did not translate this term in Paul’s letters, and that the KJV leaves it alone in the 1 Corinthians passage.

The second word carried over untranslated from the Greek text, maranatha, is actually not Greek. It comes from Aramaic: the language of first-century Palestinian Jews, and so the language that Jesus spoke. The New Testament preserves numerous words and phrases in Aramaic. However, Paul typically stuck with Greek–making his use of this Aramaic phrase stand out all the more.

As the Greek text makes clear, Maranatha is actually not one word, but two: μαράνα θά (that is, marana tha). The Greek letters transliterate the Aramaic מָרַנָא תָא : mar, meaning “Lord,” with the first plural pronominal suffix na (hence, “our Lord”), and the imperative form of the verb ‘atha: “come.” This phrase appears nowhere else in the New Testament. However, it is found in the Didache, an early Jewish-Christian book of church discipline dating to the late first-early second century CE. Here, as in Paul, it appears to be a benediction, although in the Didache it comes at the end of the eucharistic prayer:

May grace come and may this world pass away.

Hosanna to the God of David.

If any man is holy, let him come;

if any man is not, let him repent. Maran Atha. Amen (translated by J.B. Lightfoot, Apostolic Fathers; in the Greek text, 10:6 [note that in Lightfoot, this passage is 10:11-14).

As an added wrinkle, it should be noted that in Didache 10:6, the phrase is rendered maran atha, rather than, as in 1 Cor 16:22, marana tha. This may suggest a different assumed meaning: “Our Lord has come.” As Andrew Messmer notes in his recent article on this expression (“Maranatha [1 Corinthians 16:22]: Reconstruction and Translation Based on Western Middle Aramaic,” Journal of Biblical Literature 139 [2020]: 361–83), that was the meaning assumed by Jerome, John Chrysostom, and Erasmus (Messmer, 362), and it is still, he argues, the best-supported translation (Messmer, 382-83).

Still, while early evidence for the imperative form tha assumed by 1 Cor 16:22 is admittedly lacking, the imperative is certainly found in later Aramaic, and absence of evidence is not evidence of absence! Further, I would argue that the translation “Our Lord, come!” is far more likely in Paul’s theology, which looks earnestly and hopefully to Christ’s return, and that it better fits the liturgical contexts, both in 1 Corinthians and in the Didache. So to you all, in the midst of war and uncertainty, I say in this season of hopeful expectancy, Maranatha! Come, Lord Jesus.

AFTERWORD:

Prayers for this season, from Revised Common Lectionary Prayers, 2002. Consultation on Common Texts admin. Augsburg Fortress.

God of justice and peace,

from the heavens you rain down mercy and kindness,

that all on earth may stand in awe and wonder

before your marvelous deeds.

Raise our heads in expectation,

that we may yearn for the coming day of the Lord

and stand without blame before your Son, Jesus Christ,

who lives and reigns for ever and ever. Amen.

Give us ears to hear, O God,

and eyes to watch,

that we may know your presence in our midst

during this holy season of joy

as we anticipate the coming of Jesus Christ. Amen.

When I visit my father, who turns 88 this month (Happy birthday, Daddy!). we often watch old movies together–especially old Westerns. You never have to wonder who the good guys are in those old oaters! They are always dressed the part: clean-cut, clean shaven, and wearing white hats. The villains by contrast are scruffy, mustachioed, and wear black.

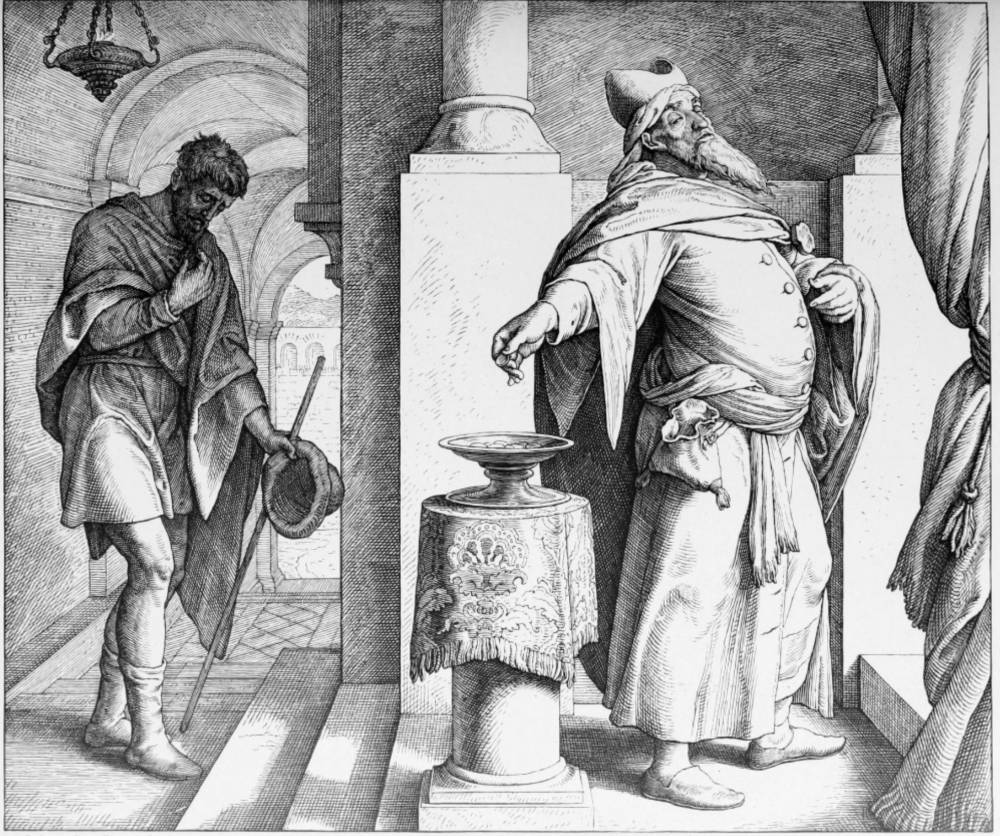

When I visit my father, who turns 88 this month (Happy birthday, Daddy!). we often watch old movies together–especially old Westerns. You never have to wonder who the good guys are in those old oaters! They are always dressed the part: clean-cut, clean shaven, and wearing white hats. The villains by contrast are scruffy, mustachioed, and wear black. So, when “Have Gun, Will Travel” appeared on television in 1957, it was something of a shock. Its main character, Paladin (expertly portrayed through its six-year run by Richard Boone), wasn’t a sheriff or a cowboy, but a gunfighter for hire. Paladin wore black. He looked, dressed, and often talked like a villain—yet he was the hero. Sometimes, in those short, often very well-written episodes, Paladin would wind up changing sides–fighting for the people he believed to be in the right, rather than the ones who had hired him.

So, when “Have Gun, Will Travel” appeared on television in 1957, it was something of a shock. Its main character, Paladin (expertly portrayed through its six-year run by Richard Boone), wasn’t a sheriff or a cowboy, but a gunfighter for hire. Paladin wore black. He looked, dressed, and often talked like a villain—yet he was the hero. Sometimes, in those short, often very well-written episodes, Paladin would wind up changing sides–fighting for the people he believed to be in the right, rather than the ones who had hired him. Likewise, in the first century, the tax collector most definitely would have been seen as the villain. Tax collectors were collaborators with the Roman military occupation. They were famously corrupt, typically collecting from the people far more than the Romans actually demanded, and living well off the proceeds (

Likewise, in the first century, the tax collector most definitely would have been seen as the villain. Tax collectors were collaborators with the Roman military occupation. They were famously corrupt, typically collecting from the people far more than the Romans actually demanded, and living well off the proceeds (

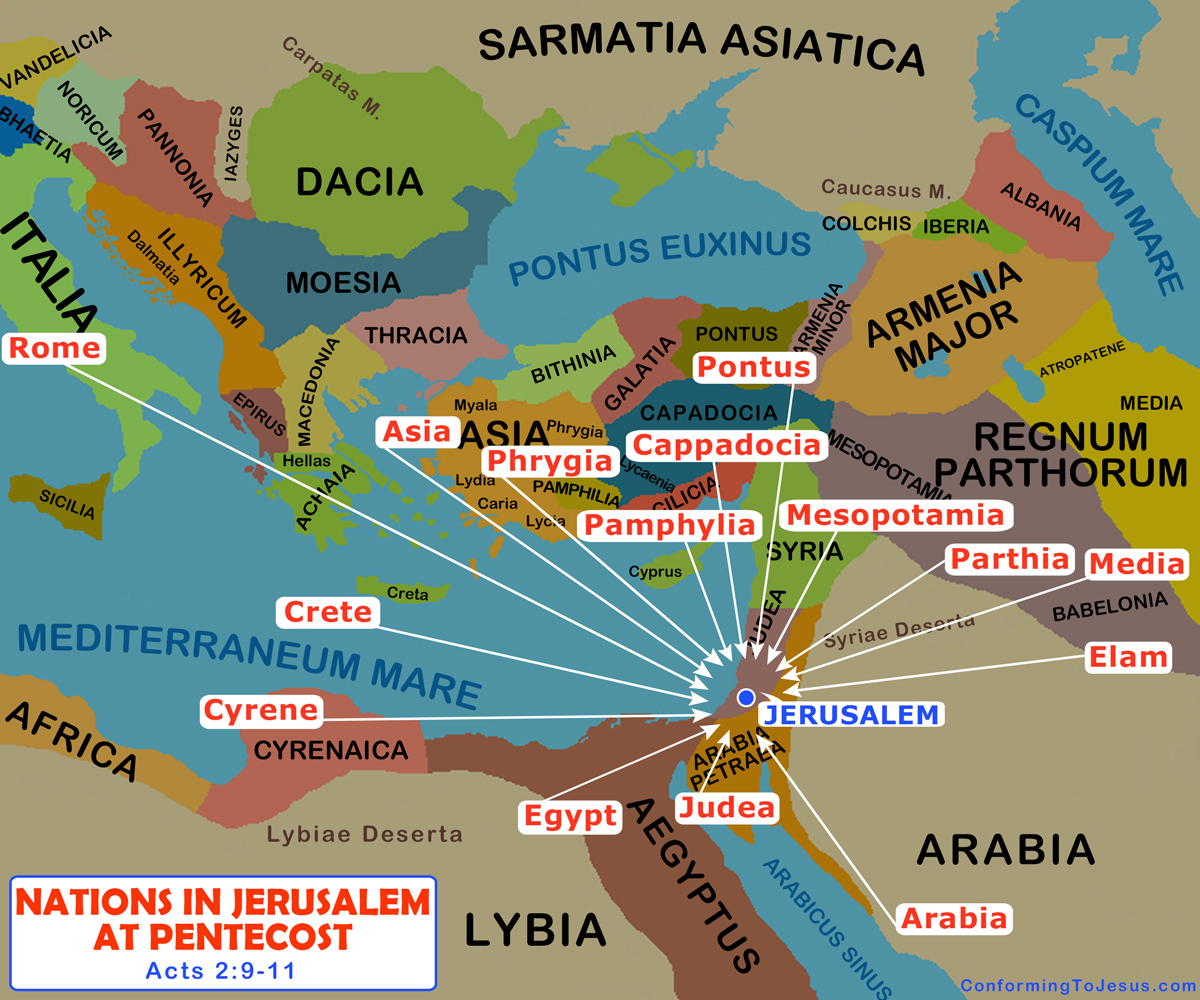

Sunday is Pentecost, which means that bewildered lay readers (and more than a few preachers!) across the church will once again be wrestling with the jawbreaking, tongue-tangling list of place names (go

Sunday is Pentecost, which means that bewildered lay readers (and more than a few preachers!) across the church will once again be wrestling with the jawbreaking, tongue-tangling list of place names (go  Meanwhile, Jesus’ followers were waiting in Jerusalem as he had commanded them (

Meanwhile, Jesus’ followers were waiting in Jerusalem as he had commanded them (

![Title: Prophet Miriam [Click for larger image view]](http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/miriam33172410852_bcf5c473db_k.jpg)

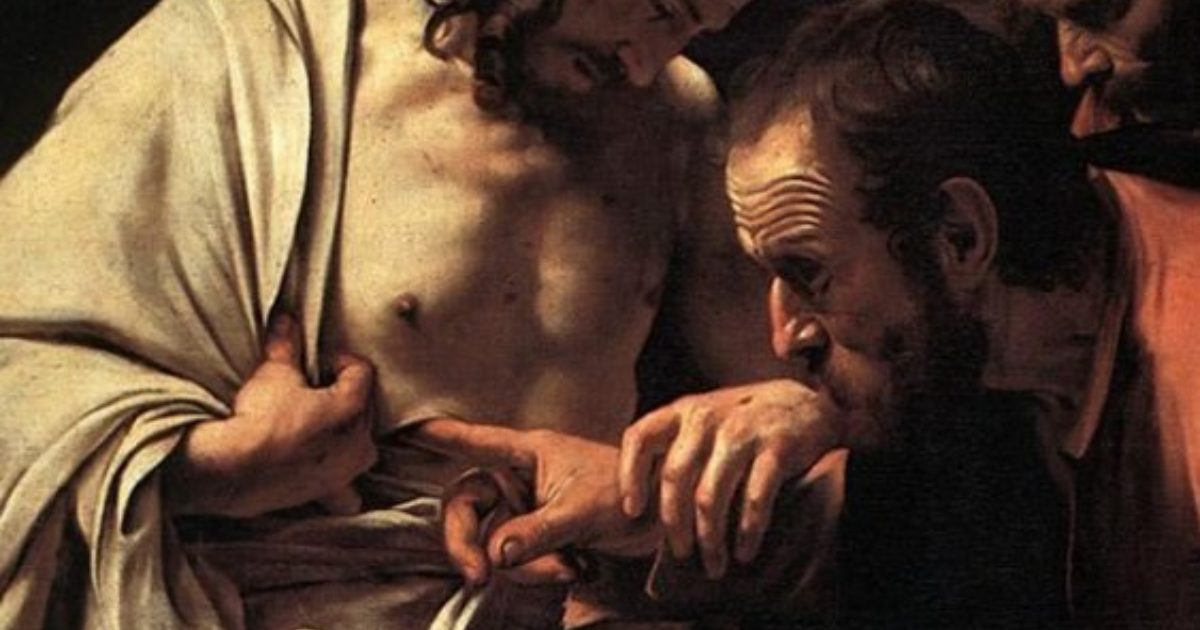

In the early church, when believers met in this holy season, they would greet one another with a hearty and enthusiastic Christe anesti–“Christ is risen!”–to which the only possible response is Allthos anesti–“He is risen indeed!”

In the early church, when believers met in this holy season, they would greet one another with a hearty and enthusiastic Christe anesti–“Christ is risen!”–to which the only possible response is Allthos anesti–“He is risen indeed!”

As we approached Jerusalem

As we approached Jerusalem

I am a lectionary preacher–a practice I commend as a way to break out of the hamster wheel of our favorite, comfortable passages and encounter the wideness–and wildness–of the Bible. But I confess that sometimes, the logic of the lectionary escapes me. The only reading from Zechariah in the Revised Common Lectionary is

I am a lectionary preacher–a practice I commend as a way to break out of the hamster wheel of our favorite, comfortable passages and encounter the wideness–and wildness–of the Bible. But I confess that sometimes, the logic of the lectionary escapes me. The only reading from Zechariah in the Revised Common Lectionary is  Both Matthew and John quote Zechariah 9:9 in their accounts of Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem (

Both Matthew and John quote Zechariah 9:9 in their accounts of Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem ( As this unit unfolds, it continues to draw distinctions between this king and other, previous kings. Although the humble mount in 9:9 derives from a long tradition of kingly processions involving the king riding an ass (Meyers and Meyers 1993, 129), this passage surely catches the point of that tradition: by riding an ass rather than a war horse or chariot, the king shows humility, and declares that he comes in peace. Yet this time, the prophet declares, this is more than theater! This king truly is humble, and not only comes in peace, but comes to bring peace: a promise our war-torn world desperately needs to hear!

As this unit unfolds, it continues to draw distinctions between this king and other, previous kings. Although the humble mount in 9:9 derives from a long tradition of kingly processions involving the king riding an ass (Meyers and Meyers 1993, 129), this passage surely catches the point of that tradition: by riding an ass rather than a war horse or chariot, the king shows humility, and declares that he comes in peace. Yet this time, the prophet declares, this is more than theater! This king truly is humble, and not only comes in peace, but comes to bring peace: a promise our war-torn world desperately needs to hear!

Patrick embraces a joyful spirituality of nature, wherein a simple herb expresses the mystery of God’s nature, the vibrancy and constancy of wind and water and stone and tree witness to God’s presence and power, and the line between the human world and the animal world, between people and deer, can blur and vanish. This St. Patrick’s Day, may we too seek God first, and so find fulfillment for ourselves and for God’s world.

Patrick embraces a joyful spirituality of nature, wherein a simple herb expresses the mystery of God’s nature, the vibrancy and constancy of wind and water and stone and tree witness to God’s presence and power, and the line between the human world and the animal world, between people and deer, can blur and vanish. This St. Patrick’s Day, may we too seek God first, and so find fulfillment for ourselves and for God’s world. The horror and violence of Vladimir Putin’s unprovoked and unjustifiable invasion of Ukraine has, thankfully, unified most of the world in opposition. But it has also seen the resurrection of a read on biblical prophecy that I have not heard since I was a young Fundamentalist, in the days before the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the U.S.S.R. Pat Robertson of the 700 Club

The horror and violence of Vladimir Putin’s unprovoked and unjustifiable invasion of Ukraine has, thankfully, unified most of the world in opposition. But it has also seen the resurrection of a read on biblical prophecy that I have not heard since I was a young Fundamentalist, in the days before the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the U.S.S.R. Pat Robertson of the 700 Club