FOREWORD: I was humbled and honored to deliver the 2021 Ira Andrews Lecture this past Sunday at Randolph-Macon College. I thank R-MC President Robert Lindgren and campus minister (and old friend!) Rev. Kendra Grimes for this invitation, and Rev. Michael Kendall, pastor of Duncan Memorial UMC, for his hospitality. It was grand to see and visit with so many old and dear friends.

What follows is derived from my lecture. If you would like to view it, you can find it online here. Ira Andrews was a good friend, a generous colleague, and a tireless advocate for the Gospel, the United Methodist Church, liberal arts education–and specifically, for the way that those ideally came together at his beloved Randolph-Macon College. May light perpetual shine upon you, my brother!

Even after sixteen wonderful years teaching seminarians at PTS, there are things I still miss about teaching at a liberal arts college. At R-MC, I had trusted colleagues in a wide range of disciplines. So, if I had a question about astronomy, physics, or science generally, I could go to my good friend George Spagna. When my research required me to decipher an article written in Italian, I was able to rely on my colleague Aouicha Hilliard for a translation.

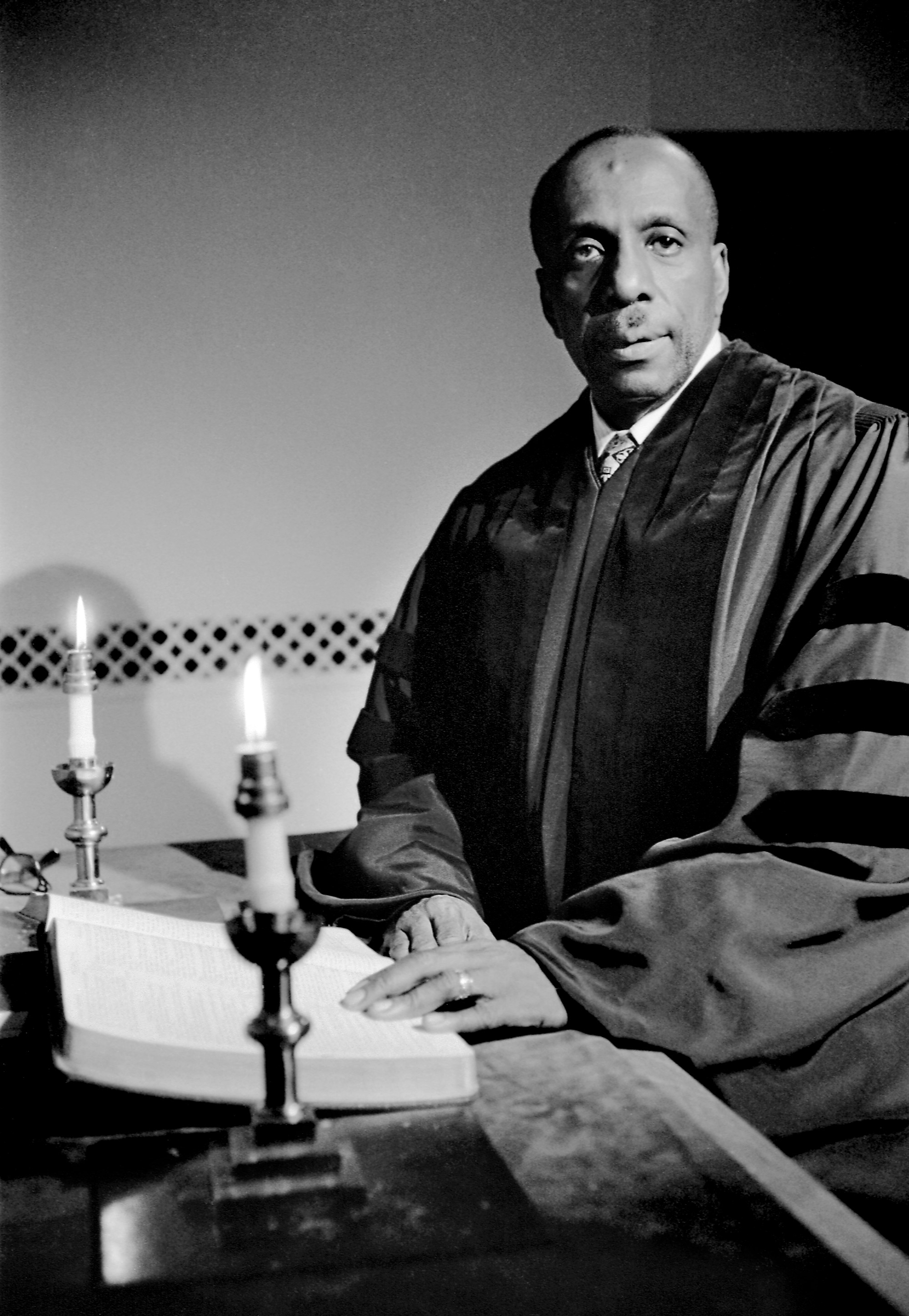

My colleagues in turn asked me about the Bible. I still recall an inquiry from my colleague in Spanish, Mark Malin. I cannot remember Mark’s question, but I distinctly remember how his email began: “Since you are the Bible guy. . .”. Immediately I thought, “That is exactly who I am! I love the Bible: I love studying it, I love teaching it, and most of all, I love the God revealed in its pages. I am a Bible guy.” When, eight years ago, I began this blog, I knew what I had to call it. Today, I have retired after 33 years of guiding college and seminary students through the Scriptures, but I am still certain that this is my calling. I am a Bible guy!

But for these last sixteen years, teaching seminarians, I have been preaching to the choir! Students coming into my classroom already valued the Scriptures, and accepted that the Bible matters. That was not the case at R-MC! Every term, and more and more as the years went by, I had students in my classes who had never set foot in a church, synagogue, or mosque; who had never opened a Bible before. Once, when Ira and I were discussing the increasing secularity of our students, he looked at me with a twinkle in his eye and said, “Steve, we’re missionaries!”

So: on the first day of class, I would say to my students, “I know why most of you are here. R-MC requires you to take two courses in philosophy or religion (or both), and you have picked Bible. I am fine with that. My job is to persuade you that you made a good choice!” I would then proceed to share with them some reasons why, in our culture, the Bible matters.

American legal and political traditions, I would tell them, derive from English common law, which is based in turn–at least, in principle–on moral and ethical ideals drawn from Scripture. Specifically, our laws build on the foundation laid in the Decalogue (Exod 20:1-17; Deut 5:1-22): respect for life, for property, loyalty to one’s commitments, wishing the other’s good–the principles that make human community possible.

Next, I would take my students to Gen 1:14-19, where the priests of ancient Israel describe God’s creation of the sun, moon, and stars. These heavenly bodies are called in Hebrew me’orot, that is, lights: a big light to rule the sky at day; a little light and a generous scattering of tiny lights to adorn the heavens at night.

The sun, moon, and stars are not gods or goddesses, but merely lights in the sky: objects, not persons or powers! Once we understand that we live in a world of objects—in short, once our world is disenchanted—we can begin the attempt to understand their interrelationships. By observation and experiment, we can begin to formulate hypotheses and test them; we can make predictions about what our world will do. The ancient Israelite priests who wrote Genesis 1 were not scientists, but the step that they took in Genesis 1:14-19 made our scientific and technological age possible.

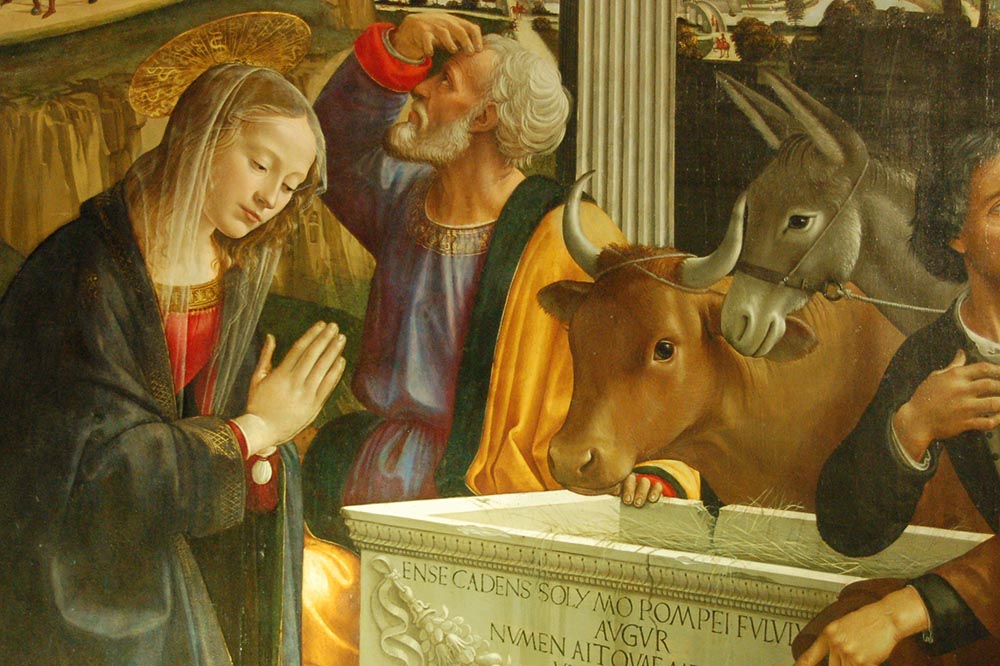

Finally, I would share with my class the words of that great English poet, artist, and mystic William Blake: “The Old and New Testaments are the Great Code of Art” (cited by Northrop Frye in The Great Code: The Bible and Literature [New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982], xvi). In the West, you cannot look at a sculpture or a painting, go to a play or a movie, read a poem or a novel, without encountering images, ideas, even plot lines taken from the pages of Scripture.

That is what I used to say to my classes, and I could say the same now. But today, I would need to say something more. Today, we are in the midst of a global pandemic. COVID-19 has taken the lives of nearly five million people world -wide; 741,231 in the U.S. alone. And yet, some still refuse vaccines or masks, and say that they do so because of their faith.

Some who mobbed our nation’s capital on January 6 carried crosses, or wore t-shirts with Christian slogans–believing, with Evangelical author Eric Metaxas, that “Jesus is with us in this fight.” In these days of crisis and division, white Christian nationalists believe that the church belongs to them, and to those like them–and that the Bible tells them so.

These groups, and many like them, treat the Bible I love, not as a source of light and healing, but as weapon: a bludgeon to beat down their adversaries. We need to say “no” to these groups. But to oppose them effectively, we need to know what the Bible actually says.

Let me give you an example of what I mean. On September 18, 2021, one of the speakers at a meeting of the American Association of Christian Counselors (AACC) was Christian author Josh McDowell. His talk took aim at Critical Race Theory, often abbreviated as CRT—a common bugaboo of Fox News commentators and of many white Evangelicals, which says that racism is not simply a matter of individual bad choices or bad actors, but rather a systemic and institutional problem, woven into the structures of our society.

Let me give you an example of what I mean. On September 18, 2021, one of the speakers at a meeting of the American Association of Christian Counselors (AACC) was Christian author Josh McDowell. His talk took aim at Critical Race Theory, often abbreviated as CRT—a common bugaboo of Fox News commentators and of many white Evangelicals, which says that racism is not simply a matter of individual bad choices or bad actors, but rather a systemic and institutional problem, woven into the structures of our society.

McDowell told those Christian counselors that CRT “negates all the biblical teaching” about racism — because it focuses on systems rather than the sins of the human heart and said today’s definition of “social justice” is not biblical. “There’s no comparison to what is known today as social justice with what the Bible speaks of as justice,” he said. “With CRT they speak structurally. The Bible speaks individually. Make sure you get that. That’s a big difference.” The Bible, according to Mr. McDowell, only focuses on individual sin, not social or structural sin.

Mr. McDowell went on to say,

I do not believe Blacks, African Americans, and many other minorities have equal opportunity. Why? Most of them grew up in families where there is not a big emphasis on education, security — you can do anything you want. You can change the world. If you work hard, you will make it. So many African Americans don’t have those privileges like I was brought up with.

These racist remarks were rightly and roundly condemned, and Mr. McDowell’s speech was removed from the AACC website. To his credit, he later apologized:

At a recent conference, I made comments about race, the black family, and minorities that were wrong and hurt many people. It breaks my heart to know what deep pain I have caused.

Mr. McDowell announced that he was stepping back from ministry, to enter a “season of listening.”

I hope he means it, friends. Still, the problem is that Mr. McDowell’s attitudes toward race and society are inseparable from the way that he and many white Evangelicals choose to read the Bible: as about individuals, not society or social justice. These claims about Scripture are simply wrong. Note that this is not a matter of opinion! We aren’t dependent on someone to tell us what the Bible says—we have Bibles of our own, and can read them for ourselves.

Far from being an unbiblical idea, social justice is a consistent and persistent part of the prophetic witness. The prophets spoke, not to isolated individuals, but to their people, who were called to account not merely individually, but corporately. Certainly that was the case for Amos, who addresses his message to the entire northern kingdom:

The Lord proclaims to the house of Israel:

Seek me and live (Amos 5:4).

In the Talmud, that great compendium of rabbinic tradition, Rabbi Simlai teaches that although there are 613 commandments in Torah, in Amos they are boiled down to one: “Seek the LORD, and live” (b. Makkot 23b-24a)! The alternative, Amos declares, is destruction for the house of Joseph and Israel (that is, the northern kingdom):

Seek the LORD and live,

or else God might rush like a fire against the house of Joseph.

The fire will burn up Bethel, with no one to put it out (Amos 5:6).

Why? Because, Amos says,

They hate the one who judges at the city gate,

and they reject the one who speaks the truth.

Truly, because you crush the weak,

and because you tax their grain,

you have built houses of carved stone,

but you won’t live in them;

you have planted pleasant vineyards,

but you won’t drink their wine (Amos 5:10-11).

Note that, in Hebrew, the “yous” in this passage are plural (like “y’all” in the South, or “yinz” in Pittsburgh!). Amos is addressing, not isolated individuals, but a society.

Amos 5:21-24 is, frankly, terrifying:

I hate, I reject your festivals;

I don’t enjoy your joyous assemblies.

If you bring me your entirely burned offerings and gifts of food

I won’t be pleased;

I won’t even look at your offerings of well-fed animals.

Take away the noise of your songs;

I won’t listen to the melody of your harps (Amos 5:21-23).

God rejected the worship of Israel–but why? What does God want, if not beautiful, emotionally stirring worship? We know well Amos’ answer to that question:

But let justice roll down like waters,

and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream (Amos 5:24).

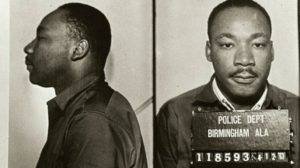

We know those words well because Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. famously quoted them, in his Letter From a Birmingham Jail and in his “I Have A Dream” speech. Dr. King used these words in exactly the same way that Amos used them–to call a society to repentance.

A few pages later in our Bibles, the prophet Micah similarly addresses the sins of the southern kingdom of Judah. God brings a lawsuit (Hebrew rib; the NRSV reads “case” or “controversy”) against God’s own people:

Hear what the LORD is saying:

Arise, lay out the lawsuit before the mountains;

let the hills hear your voice!

Hear, mountains, the lawsuit of the LORD!

Hear, eternal foundations of the earth!

The LORD has a lawsuit against his people;

with Israel he will argue (Micah 6:1-2).

The LORD reminds Judah of their past: of who they are, and who God is:

My people, what did I ever do to you?

How have I wearied you? Answer me!

I brought you up out of the land of Egypt;

I redeemed you from the house of slavery.

I sent Moses, Aaron, and Miriam before you (Micah 6:3-4).

Next, much like Amos, Micah asks, “What does the LORD expect of us? What does God want?”

With what should I approach the Lord

and bow down before God on high?

Should I come before him with entirely burned offerings,

with year-old calves?

Will the Lord be pleased with thousands of rams,

with many torrents of oil?

Should I give my oldest child for my crime;

the fruit of my body for the sin of my spirit? (Micah 6:6-7).

Micah’s answer, too, is much like Amos’:

He has told you, human one, what is good and

what the LORD requires from you:

to do justice, embrace faithful love, and walk humbly with your God (Micah 6:8).

In Hebrew, the word rendered “faithful love” in the CEB is the gloriously untranslatable khesed (the NRSV reads “kindness,” the KJV has “mercy”)–a word that means steadfast love, covenant loyalty–the commitment of the whole self to God and to the justice that God loves and requires.

In Daniel 9:4-11, Daniel is reading Jeremiah’s prophecy of seventy years of exile (see Jeremiah 29:10; 25:11– 12). Daniel cannot understand why God’s promise has been delayed, and so, fasting and mourning in sackcloth and ashes, he offers his corporate prayer of confession. In this book, Daniel is presented as a conspicuously righteous and pious man. But recognizing that, as an Israelite, he shares responsibility for the sins of his people, he prays for and repents of the sins of all Israel (note the emphasized words in this powerful prayer):

Please, my Lord—you are the great and awesome God, the one who keeps the covenant, and truly faithful to all who love him and keep his commands: We have sinned and done wrong. We have brought guilt on ourselves and rebelled, ignoring your commands and your laws. We haven’t listened to your servants, the prophets, who spoke in your name to our kings, our leaders, our parents, and to all the land’s people. Righteousness belongs to you, my Lord! But we are ashamed this day—we, the people of Judah, the inhabitants of Jerusalem, all Israel whether near or far, in whatever country where you’ve driven them because of their unfaithfulness when they broke faith with you. LORD, we are ashamed—we, our kings, our leaders, and our parents who sinned against you. Compassion and deep forgiveness belong to my Lord, our God, because we rebelled against him. We didn’t listen to the voice of the LORD our God by following the teachings he gave us through his servants, the prophets. All Israel broke your Instruction and turned away, ignoring your voice. Then the curse that was sworn long ago—the one written in the Instruction from Moses, God’s servant—swept over us because we sinned against God (Daniel 9:4-11).

Some may say, “Well, yeah, but that is all on the left-hand side of the Bible. Jesus taught individual accountability.” But, is that so? Remember that Rabbi Simlai looked for the core of the 613 commandments of Torah, finding them all summed up in Amos 5:4. The question of the greatest commandment was addressed by Jesus, too: in Matthew 22:34-40; Mark 12:28-34 (the Gospel reading for this Sunday!); and Luke 10:25-28. These accounts differ in small points: in Matthew, the expert on the Jewish law seeks to test Jesus when he asks his question; in Mark, his question is sincere; in Luke, it is Jesus who questions the expert. In all three, however, Jesus’ answer is the same: I can’t give you just one, I have to give you two!

The first commandment comes from Deuteronomy 6:5 (the alternate Hebrew Bible reading for Sunday): “Love the LORD your God with all your heart, all your being, and all your strength.” The heart (lebab in Hebrew) is the center of the will: loving God with all your heart means loving God as much as you can. To love God with all one’s being (Hebrew nephesh should not be translated as “soul;” it refers, as the CEB translation “being” indicates, to the whole of oneself) is another way of saying that one is to love God entirely. The last word, typically translated “strength” or “might,” is me’od in Hebrew; it means literally “much” or “very.” We are to love God with our muchness–again, as much as we are possibly capable of loving!

The second commandment is Leviticus 19:18: “You must not take revenge nor hold a grudge against any of your people; instead, you must love your neighbor as yourself; I am the LORD.” In Matthew 22:39, Jesus expressly connects this commandment to the first, saying that it is “like it.” Responsibility to our community is not optional! After all, in the prayer that Jesus taught us, we do not pray “My Father,” but “OUR Father.” Jesus taught us to pray, not “forgive me my trespasses,” but “forgive US OUR trespasses.” Communal responsibility and social justice are common, prominent, universal themes in the whole of Scripture.

Why, then, can’t Mr. McDowell see it? Perhaps because, as an Evangelical Christian, he believes, as I do, in the importance of a personal, individual relationship with Christ. It is far too easy to see in Scripture not what is there on the page, but what we expect to see; to hear only what we expect to hear. But this need not be an either/or, friends. After all, Micah called not only for justice, but also for a personal, humble walk with God. There need be no conflict between personal faith and social justice.

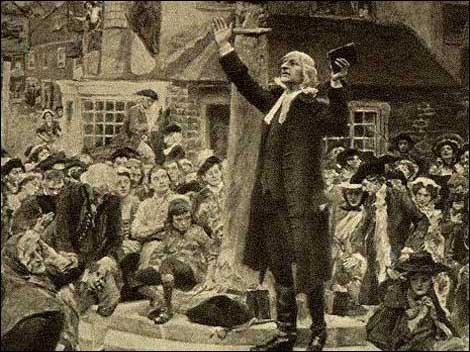

Friends, we must challenge those who arrogantly claim that the Bible legitimates their hatred and division—but how? I remain persuaded that the only way to beat bad Bible is with good Bible. We need actually to READ the Bible ourselves, in big hunks! We need to study this ancient text, so foundational for our society, in the church and in the academy. We need to ask hard questions, of the text and of one another. We need to find and engage with reliable scholars and teachers, old and new. To reclaim the Bible as a positive force for good in our world, we must all become Bible Guys.

AFTERWORD:

October 31 is called Halloween (“Hallow E’en”) for the same reason December 31 is called “New Year’s Eve,” or December 24 “Christmas Eve.” Sunday is of course the day before November 1, All-Hallows Day–hence, All-Hallows Eve. All-Hallows, or All-Saints, Day began in the days of Pope Boniface IV as a feast day for all martyrs, and was first celebrated on May 13, 609. Pope Gregory III (731-741) shifted the focus from the martyrs to the celebration of all the saints who lack a feast day of their own (and by extension, of all who have died in the Lord), and as such All-Saints was declared an official holy day of the church by Pope Gregory IV in 837.

October 31 is called Halloween (“Hallow E’en”) for the same reason December 31 is called “New Year’s Eve,” or December 24 “Christmas Eve.” Sunday is of course the day before November 1, All-Hallows Day–hence, All-Hallows Eve. All-Hallows, or All-Saints, Day began in the days of Pope Boniface IV as a feast day for all martyrs, and was first celebrated on May 13, 609. Pope Gregory III (731-741) shifted the focus from the martyrs to the celebration of all the saints who lack a feast day of their own (and by extension, of all who have died in the Lord), and as such All-Saints was declared an official holy day of the church by Pope Gregory IV in 837.

The feast was shifted from spring to fall in response to the Celtic celebration Samhain (pronounced “SOW-en;” called El Dia de Los Muertos [the Day of the Dead] in Spain), an ancient festival of the quarter-year, falling between the autumnal equinox and the winter solstice. In Celtic culture, Samhain was believed to be a night when the borders between this world and the next became particularly thin, so that the unquiet dead could cross over and molest the living. Food offerings, lamps, and even the severed heads of enemies (grimly recalled, perhaps, by jack o’lanterns) were set out to appease or turn aside the ghosts. When the Celts became Christians, this night was transformed by the realization that Jesus Christ had triumphed over death, hell, and the grave. Death, and the dead, no longer needed to be feared.

Some Christians argue that we should not celebrate Hallowe’en at all–that to do so is to flirt with the demonic, and to open the door to evil influences. I disagree. I think it is fitting that this night, which used to be a grim and grisly night of fear, has become a night of laughter and joy, when it is little children who come to our doors for treats! As the Reformer Martin Luther once observed, “The best way to drive out the devil, if he will not yield to texts of Scripture, is to jeer and flout him, for he cannot bear scorn.”

Happy Halloween, friends, and a joyous All Saints Day–and to my Dad Bernard Tuell, the best saint I know–happy birthday!

![]()

Whether because my attention was drawn to the music rather than the words, or because I let the beautiful Latin phrases wash over me without worrying about what they meant, I am ashamed to confess that I only recently realized that this hymn is based on Luke’s account of Jesus’ humble birth:

Whether because my attention was drawn to the music rather than the words, or because I let the beautiful Latin phrases wash over me without worrying about what they meant, I am ashamed to confess that I only recently realized that this hymn is based on Luke’s account of Jesus’ humble birth:

In the Hebrew Bible reading for this fourth Sunday of Advent,

In the Hebrew Bible reading for this fourth Sunday of Advent,

So, why the eight nights of Hanukkah, with their eight lights? Following the liberation of Jerusalem, Judas Maccabeus summoned faithful priests to reconsecrate the temple and its altar, defiled by the idolatrous rites that had been performed there under Antiochus’ rule. But, according to the tradition, they hit a snag. Talmud says:

So, why the eight nights of Hanukkah, with their eight lights? Following the liberation of Jerusalem, Judas Maccabeus summoned faithful priests to reconsecrate the temple and its altar, defiled by the idolatrous rites that had been performed there under Antiochus’ rule. But, according to the tradition, they hit a snag. Talmud says:

Let me give you an example of what I mean. On September 18, 2021, one of the speakers at a meeting of the American Association of Christian Counselors (AACC) was

Let me give you an example of what I mean. On September 18, 2021, one of the speakers at a meeting of the American Association of Christian Counselors (AACC) was

October 31 is called Halloween (“Hallow E’en”) for the same reason December 31 is called “New Year’s Eve,” or December 24 “Christmas Eve.” Sunday is of course the day before November 1, All-Hallows Day–hence, All-Hallows Eve. All-Hallows, or All-Saints, Day began in the days of Pope Boniface IV as a feast day for all martyrs, and was first celebrated on May 13, 609. Pope Gregory III (731-741) shifted the focus from the martyrs to the celebration of all the saints who lack a feast day of their own (and by extension, of all who have died in the Lord), and as such All-Saints was declared an official holy day of the church by Pope Gregory IV in 837.

October 31 is called Halloween (“Hallow E’en”) for the same reason December 31 is called “New Year’s Eve,” or December 24 “Christmas Eve.” Sunday is of course the day before November 1, All-Hallows Day–hence, All-Hallows Eve. All-Hallows, or All-Saints, Day began in the days of Pope Boniface IV as a feast day for all martyrs, and was first celebrated on May 13, 609. Pope Gregory III (731-741) shifted the focus from the martyrs to the celebration of all the saints who lack a feast day of their own (and by extension, of all who have died in the Lord), and as such All-Saints was declared an official holy day of the church by Pope Gregory IV in 837. This past Sunday,

This past Sunday,

.jpg)