This Sunday, the first Sunday after Pentecost, is Trinity Sunday. The Old Testament reading for the day is Proverbs 8:22-31. The ancient sages of Israel, of course, would not have thought about God in Trinitarian terms. Still, in Israel’s traditions, a particular attribute or manifestation of God can be treated as an independent entity, or hypostasis. Indeed, Hebrews intriguingly uses that very expression for Jesus, who is character tes hupostaseos auto (“the imprint of God’s being,” Heb 1:3): that is, Jesus is the hypostasis of God’s very character!

In Proverbs, Wisdom is personified as a woman (1:20-33; 8:1-36; 9:1-6), as the Hebrew word for wisdom (khokmah) is feminine. Influenced by this tradition, the Apocryphal book of Wisdom (sometimes called “Wisdom of Solomon”), likely written in Alexandria around the time 0f Jesus, also personifies Wisdom as a woman (for example, Wisd 6:12-25; 7:7—9:18), whom the sage seeks as a bride (Wisd 8:2)!

Much as in Genesis creation begins with a Word (Gen 1:3-4), so in Proverbs creation begins with Wisdom. This is stated early on: “The LORD laid the foundations of the earth with wisdom, establishing the heavens with understanding” (Prov 3:19). However, in Prov 8, Wisdom herself speaks:

The LORD created me [Hebrew qanani; better “acquired me”] at the beginning of his way,

before his deeds long in the past.

I was formed in ancient times,

at the beginning, before the earth was.

When there were no watery depths, I was brought forth,

when there were no springs flowing with water.

Before the mountains were settled,

before the hills, I was brought forth;

before God made the earth and the fields

or the first of the dry land.

I was there when he established the heavens,

when he marked out the horizon on the deep sea,

when he thickened the clouds above,

when he secured the fountains of the deep,

when he set a limit for the sea,

so the water couldn’t go beyond his command,

when he marked out the earth’s foundations.

I was beside him as a master of crafts [Hebrew ‘amon; as the CEB footnote observes, its meaning is uncertain]

I was having fun,

smiling before him all the time,

frolicking with his inhabited earth

and delighting in the human race (Prov 8:22-31).

Understanding Wisdom’s role in the creation of the world depends upon the translation of the word ‘amon in Prov 8:30—a word which unfortunately appears only here. The CEB “master of crafts” and NRSVue “master worker,” like the Greek Septuagint harmozousa (“fitting together”?) and the Latin Vulgate cuncta conponens (“forming all things;” compare Wisd 7:21[22]; 8:6, which describes Wisdom as a technitis: a designer, artificer, or technician) suggest a derivation from the Akkadian ummanu, “workman.”

The Greek translator Aquila’s rendering tithenoumene may mean someone brought up (as in the Greek text of Lam 4:5 or Sir 30:9)—hence the translation in the NRSVue footnote, “little child.” William Brown reads “I was beside him growing up” (The Seven Pillars of Creation: The Bible, Science, and the Ecology of Wonder [New York: Oxford, 2010], 164), and observes that “the repeated reference to play at the end” also supports the image of Wisdom as a growing child (Brown 2010, 286 n 16).

On the other hand, Robert Alter (The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary. Vol 3: The Writings [New York: W. W. Norton, 2019], 380) has “I was by him, an intimate.” Such a reading could be supported by the use of the Hebrew qanani in Prov 8:22. While the CEB translates this as “created me,” a better reading would be “acquired me”—perhaps, as a wife (see Ruth 4:5). So too the Septuagint harmozousa for ‘amon may mean “betrothed” (see 2 Cor 11:2). This reading also fits the emphasis on play in Prov 8:30-31, although of course in a different sense: “Before there were creatures to occupy God’s attention, Wisdom was His delightful and entertaining bosom companion” (Alter 2019, 380).

In his discussion of ‘amon, Richard Clifford looks to “the relatively well-attested picture of the Mesopotamian transmission of wisdom, originating with the gods and concluding with human sages and their institutions” (“The Community of the Book of Proverbs,” in Constituting the Community: Studies on the Polity of Ancient Israel in Honor of S. Dean McBride, Jr., ed. John T. Strong and Steven Tuell [Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2005], 282). From Enki/Ea, the god of wisdom, the stream ran through “the mythic sages or culture-bringers of the primordial time”—the apkallu and the ummanu (!)—and so finally to the Babylonian wisdom schools. In Prov 8:30, then, Wisdom is herself a sage—counsellor to the LORD, and teacher of the sages of Israel.

Perhaps we need not select from among these possibilities a single meaning for ‘amon. After all, as Carol Fontaine notes, Wisdom’s role in Proverbs is complex and multi-faceted:

Speaking directly to prospective students, Woman Wisdom sounds like prophet, lover, counselor, scolding mother, or goddess as she expounds the goals of the sages and entices her hearers with the promise of rich reward: life itself (“Proverbs,” in The HarperCollins Bible Commentary, ed. James Luther Mays [San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2000], 449).

Many descriptions of Christ reflect that ancient image of Wisdom. Certainly the New Testament speaks of Christ as the agent of God’s creation. The apostle Paul writes:

Granted, there are so-called “gods,” in heaven and on the earth, as there are many gods and many lords. However, for us believers,

There is one God the Father.

All things come from him, and we belong to him.

And there is one Lord Jesus Christ.

All things exist through him, and we live through him (1 Cor 8:5-6).

The prologue to the Gospel of John explicitly picks up on the language of both Genesis and Proverbs:

In the beginning was the Word

and the Word was with God

and the Word was God.

The Word was with God in the beginning.

Everything came into being through the Word,

and without the Word

nothing came into being.

What came into being

through the Word was life,

and the life was the light for all people.

The light shines in the darkness,

and the darkness doesn’t extinguish the light (John 1:1-5).

By describing Jesus as the pre-existent Word (Greek he logos) of God “which became flesh and lived among us” (John 1:15), the author of the Fourth Gospel alludes to Genesis 1, where God speaks the world into being: an allusion made even more evident by the opening words of this gospel: en arche, “In [the] beginning,” which mirrors the opening of Genesis in the Septuagint.

In the philosophical world of the first century, however, the Greek logos had other resonances. Among the Stoics, logos referred to the rational principle underlying reality—the very intelligibility, we might say, of the cosmos. As the Divine logos, then, Christ is not only the means by which God brought the world into being, but also the very principle of meaning and order in reality–much like Wisdom in Proverbs 8.

Elsewhere in the New Testament, many other passages further underline and emphasize Christ’s role in the creation, maintenance, and destiny of the cosmos. According to Hebrews 1:2, “God made his Son the heir of everything and created the world through him.” Colossians 1:15-17 confesses,

The Son is the image of the invisible God,

the one who is first over all creation,

Because all things were created by him:

both in the heavens and on the earth,

the things that are visible and the things that are invisible.

Whether they are thrones or powers,

or rulers or authorities,

all things were created through him and for him.

He existed before all things,

and all things are held together in him.

Ephesians identifies Jesus as the telos—that is, the purpose and goal—of the cosmos. From the beginning, “This is what God planned for the climax of all times: to bring all things together in Christ, the things in heaven along with the things on earth” (Eph 1:10).

This way of describing the person and work of Christ in creation is closely related to the depiction of Wisdom in Israel’s traditions. For example, compare Col 1:15 and Heb 1:3 to the description of Wisdom in Wisd 7:26: “She’s the brightness that shines forth from eternal light. She’s a mirror that flawlessly reflects God’s activity. She’s the perfect image of God’s goodness.”

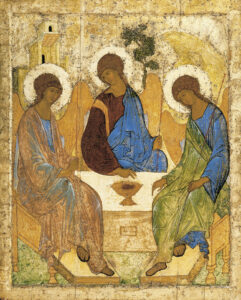

The treatment of Wisdom as a hypostasis likely witnesses to the desire of the sages to find a way of speaking of the Divine in ways at once transcendent and imminent. After all it is Wisdom, and not, expressly, the transcendent God, who is imminently “frolicking with [God’s] inhabited earth and delighting in the human race” (Prov 8:22-31). The language of Israel’s sages is of course not Trinitarian, but arguably speaks to a need and desire similar to that felt by early Christians, which led them ultimately to the confession of the Trinity.

![Title: In the Beginning [Click for larger image view]](https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/creation32fudhj5498.jpg)

Theologian George Lindbeck argued that Trinitarian theology grew out of the struggle of early Christians to speak plainly about their experience of God. Early on, the first Christians needed to affirm, on the one hand, the continuity of their faith with the faith of ancient Israel: the God they loved and worshipped was the one transcendent God, who called time and space into being. But on the other hand, they had come to know God, intimately and personally, in and through Jesus. Therefore, they needed to speak of the Christ in the most exalted language possible (what Lindbeck terms “Christological maximalism”). So, the New Testament calls Jesus God’s Son (George Lindbeck, The Nature of Doctrine [Nashville: Westminster John Knox, 1984], 94).

Theologian, poet, playwright, literary critic, and from 2002 to 2012 Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams, reflecting on his debates with prominent atheists, observes

I think what’s missing sometimes is precisely that sense that when we talk about God, we’re not just talking about a thing or a person, in the sense of an individual. As a Christian, I believe in God as Trinity. I believe in God as an interweaving of personal agencies, the love and mutuality of what we call the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. In that sense, I’m not saying I believe in an impersonal God. Far from it.

But very often the God who’s being attacked and questioned by the Dawkinses and the Graylings and the Pullmans of this world is a God I don’t believe in, either: an individual who sits in the remote parts of the universe and treats the rest of the universe as an intriguing hobby for himself, rather than the God who is much more like the ocean that soaks through everything that is and yet is infinitely beyond it.

Which sounds very like Wisdom in the Old Testament, and resonates with the Wisdom Christologies of the New. Williams continues:

[The New Atheists] come up with all sorts of very neat and, as far as they go, perfectly rational arguments about how difficult it is to believe in some chap out there in midspace. I want to say, “Well, yeah. I have no interest in a chap out there in outer space, none at all.” But I am quite interested in what the infinite, unconditioned life of generosity is within which I and everything else live. And I have every interest in the story of how that life astonishingly comes to fruition in the middle of our history in the life of Jesus. Now, that’s something I do think I can spend my life thinking and praying about and something that transfigures the horizons in which we live.

On May 2, President Donald Trump signed

On May 2, President Donald Trump signed

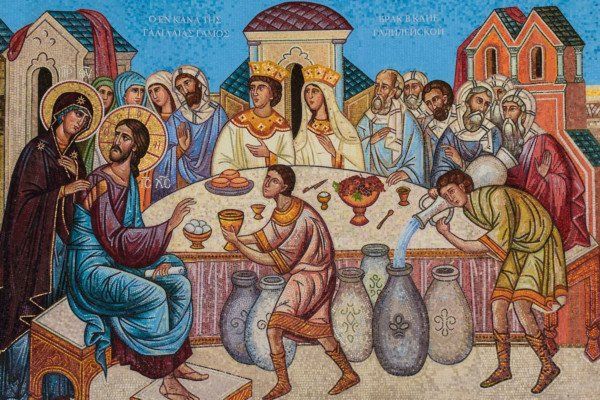

Most of the people we meet in the Bible are grownups. Adam and Eve may be brand new when we are introduced, but they are born full grown! Likewise, we meet Abraham as an adult, and Paul, and Peter. In the Gospels of

Most of the people we meet in the Bible are grownups. Adam and Eve may be brand new when we are introduced, but they are born full grown! Likewise, we meet Abraham as an adult, and Paul, and Peter. In the Gospels of

![Title: Disputation with the Doctors [Click for larger image view]](https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/Duccio_di_Buoninsegna_Disputation_with_the_Doctors.jpg) After three days (three days!) Mary and Joseph find their son in the temple, in an intense conversation with the religious leaders. We learn that even as a boy, Jesus has attained a terrifying sense of his identity and calling: “I must be in my Father’s house” (

After three days (three days!) Mary and Joseph find their son in the temple, in an intense conversation with the religious leaders. We learn that even as a boy, Jesus has attained a terrifying sense of his identity and calling: “I must be in my Father’s house” (

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/wizard-of-oz1-b3190fbf82ac4ccb92639ee98d8b9e8b.jpg)

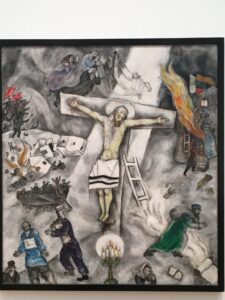

Some traditional Christian interpreters (Irenaus, Against Heresies 5.21.1; Martin Luther, Lectures on Genesis, 3.4.5) regarded Genesis 3:15 as a prediction of the coming of Christ: the Devil would strike at his heel, wounding him on the cross, but Christ would rise from the dead, and at his return crush the enemy’s head . But as John Calvin observed in his

Some traditional Christian interpreters (Irenaus, Against Heresies 5.21.1; Martin Luther, Lectures on Genesis, 3.4.5) regarded Genesis 3:15 as a prediction of the coming of Christ: the Devil would strike at his heel, wounding him on the cross, but Christ would rise from the dead, and at his return crush the enemy’s head . But as John Calvin observed in his

![Title: The birth of Jesus with shepherds [Click for larger image view]](https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/Mafa055.jpg)