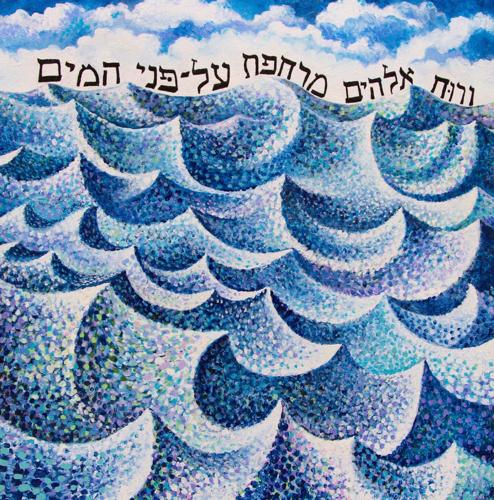

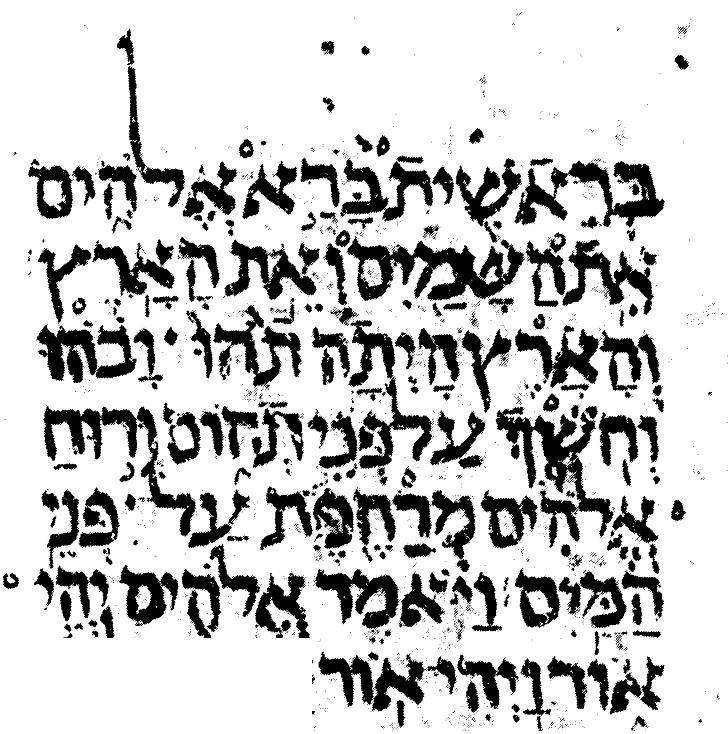

When I first began shopping my current book around, some prospective editors urged me to eliminate the Hebrew references: “You’ll just confuse your readers,” I was told. However, I remain convinced that serious Bible students are well aware that the Bible was not written in English, and know that some subtleties in the original languages may not be captured in translation.

Further, I am persuaded that questions I have relating to translation and interpretation will occur to other readers too, whether they know the original languages or not. So, in my teaching and preaching, as in my writing, I refuse to insult the intelligence of my audience, and when the text calls for it, I endeavor to guide them through the linguistic thickets–although I also try to avoid overly-technical language that will indeed frustrate and confuse rather than enlighten.

All of which is to say that today’s blog does indeed go pretty deep into the weeds of Hebrew grammar. But I am persuaded that the exegetical and theological payoff is worth the effort. To put it very simply, friends– this’ll preach.

On Day Five of the first biblical creation account (Gen 1:20-23), God addresses God’s creations for the first time: “Then God blessed them: ‘Be fertile and multiply and fill the waters in the seas, and let the birds multiply on the earth’” (Gen 1:22). The CEB translation rightly recognizes that the verbs in this verse are imperatives. But in Hebrew, the imperative doesn’t always indicate a command.

Semitic grammarians Paul Jouon and T. Muraoka note that “The imperative is the volitive mood of the second person;” it “is essentially a form for expressing the speaker’s will, wish, or desire” (A Grammar of Biblical Hebrew, Part Three: Syntax [Rome: Ponifical Biblical Institute, 1996], 378-79). The context of these imperative forms, within a blessing, suggests that they should not be rendered as commands, but rather as expressing God’s desire and intention for God’s creatures: as David Carr observes, “within a blessing, the imperative stands as a modal wish” (Genesis 1—11. International Exegetical Commentary of the Old Testament [Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2021], 43). Better would be, “May you be fruitful and multiply.”

That distinction becomes even more important when we examine Gen 1:28, which this verse foreshadows. Here, God blesses human men and women:

God blessed them and said to them, “Be fertile and multiply; fill the earth and master it.”

Unfortunately, some have tried to construct a sexual ethic out of this verse. Since, as the early Christian theologian and scholar St. Jerome (340-420) observed, “God’s first command” is, “‘Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth’” (Against Jovinianus, 1.3; cf. Gen 1:28), any sexual act that could not produce a child is contrary to God’s design and intent.

In the Mishnah (the Jewish compendium of traditional interpretations of the Torah, to which the Talmud serves as commentary) as well, this verse is construed as a commandment: but for the man, not for the woman (b. Yebamot 65b)! As the broader context of this discussion is a debate regarding the divorce of a woman who is barren or miscarries, the point would appear to be that, while men are obligated to father children if they can, women are not necessarily obligated to bear them.

However, it is essential to remember, as in Gen 1:22, that—despite its (mis)use in Christian and Jewish traditions—Gen 1:28 is a blessing, not a commandment! Grammarians Bill T. Arnold and John H. Choi note that the imperative can express a promise: “The speaker assures that the recipient of the imperative will take the action in the future, although he action itself is normally outside the power of the person receiving the order” (A Guide to Biblica Hebrew Syntax [Cambridge: Cambridge University, 2003], 64). Likely, that is the case here. As Carr observes regarding this passage,

The blessing here, as in 1:22, is formulated in Hebrew with an imperative form. This corresponds to the rule, wherein the contents of blessings, insofar as they are formulated in verbal form, are expressed with modal verb forms. . . . There is, therefore, no implication of a command to multiply or rule the earth in the imperative forms of v. 28. Instead, there is the promise of powers/capabilities (Carr 2021, 84).

When we read these opening chapters of Genesis, it is important to remember that they are neither history, nor science, nor law. They are confessions, made by communities of faith—grounded not only in universal, timeless ideas but also in the particular circumstances of their authors. Therefore, when we hear something from the priests in Gen 1:1—2:4a that we would not expect to hear, it carries particular weight.

The affirmation in Gen 1:27 that maleness and femaleness alike reflect the image of God hits like a thunderbolt: it can scarcely be ascribed to the typical attitudes of its patriarchal culture! This extraordinary valuation of the feminine need not be read, however, as restricting God’s intention for humanity to the union of male and female. Certainly Jerome, with his eloquent defense of celibacy (Against Jovinianus, 1.3), did not regard singleness as condemned by this passage!

Further, there may be a hint here about how God might be viewed. While admittedly, male images of God predominate in Scripture, female images as well can be identified. Lady Wisdom in Proverbs 8 is certainly a feminine aspect of God. In the Psalms, God appears a midwife (Ps 22:9-10), while in Hosea 11:3-4, God speaks as a mother:

Yet it was I who taught Ephraim to walk;

I took them up in my arms,

but they did not know that I healed them.

I led them

with bands of human kindness,

with cords of love.

I treated them like those

who lift infants to their cheeks;

I bent down to them and fed them.

Similarly, Jesus cries out to Jerusalem, “How often I wanted to gather your people together, just as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings. But you didn’t want that” (Matt 23:37//Lk 13:34).

God is neither male nor female, for neither masculinity nor femininity can fully capture the Divine. Attempts, then, to derive from Genesis 1 a rebuke of transgender persons, or the affirmation of a sexual binary as the God-imposed norm, are seriously misplaced. Indeed, both masculinity and femininity reflect aspects of God, who makes all humankind, of every gender, race, and nation, “in our image, according to our likeness” (Gen 1:26).

On the other hand, the call to “Be fertile and multiply; fill the earth and master it” (Gen 1:28) is no surprise: it fits neatly into the flow of the narrative from Genesis through Joshua. As God’s people endure threat after threat, seeming always on the edge of extinction, fertility is essential for their survival. In particular, Gen 1:28 prefigures the growth of the people into a great nation, despite Egyptian persecution (see Exod 1:6-7, 20) and despite the faithlessness of the wilderness generation (see Num 22:3-4), in fulfillment of God’s promise to Abraham (see Gen 15:5-6). We may question, then, whether this “first commandment” is intended as a universal imperative, or as promise to a beleaguered community.

![Title: Lift Every Voice and Sing, or, The Harp [Click for larger image view]](http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/lift-every-voice8927xc.jpg)

This past Sunday was Trinity Sunday. The lectionary

This past Sunday was Trinity Sunday. The lectionary

As with 1 John 5:7, this translation is not based on any ancient Greek text of Revelation, but on Erasmus’ sixteenth-century Textus receptus. Erasmus inserts ton sozomenon (“the ones who are saved”) after ta ethne (“the nations”) in Revelation 21:24. Neither the Latin Vulgate nor the majority Byzantine Greek text have this addition. Nestle-Aland’s critical edition of the Greek New Testament Novum Testamentum Graece doesn’t mention this insertion, even as a minor variant to be considered, and Metzger’s Textual Commentary doesn’t even discuss it.

As with 1 John 5:7, this translation is not based on any ancient Greek text of Revelation, but on Erasmus’ sixteenth-century Textus receptus. Erasmus inserts ton sozomenon (“the ones who are saved”) after ta ethne (“the nations”) in Revelation 21:24. Neither the Latin Vulgate nor the majority Byzantine Greek text have this addition. Nestle-Aland’s critical edition of the Greek New Testament Novum Testamentum Graece doesn’t mention this insertion, even as a minor variant to be considered, and Metzger’s Textual Commentary doesn’t even discuss it. So, what does text criticism mean to Bible students who do not know the original languages, and so lack access to the many texts behind the text on the page? First, the King James should not be your go-to study Bible. The language of the King James is beautiful and poetic: more often than not, the passages I have committed to memory are from its pages! For its day, the King James was an excellent translation. However, quite apart from the fact that we no longer speak in King James English, the translators in 1611 simply lacked access to the many ancient texts now available. Indeed, the oldest Hebrew manuscripts extant, the so-called Dead Sea Scrolls from Qumran, were unknown before the mid-twentieth century.

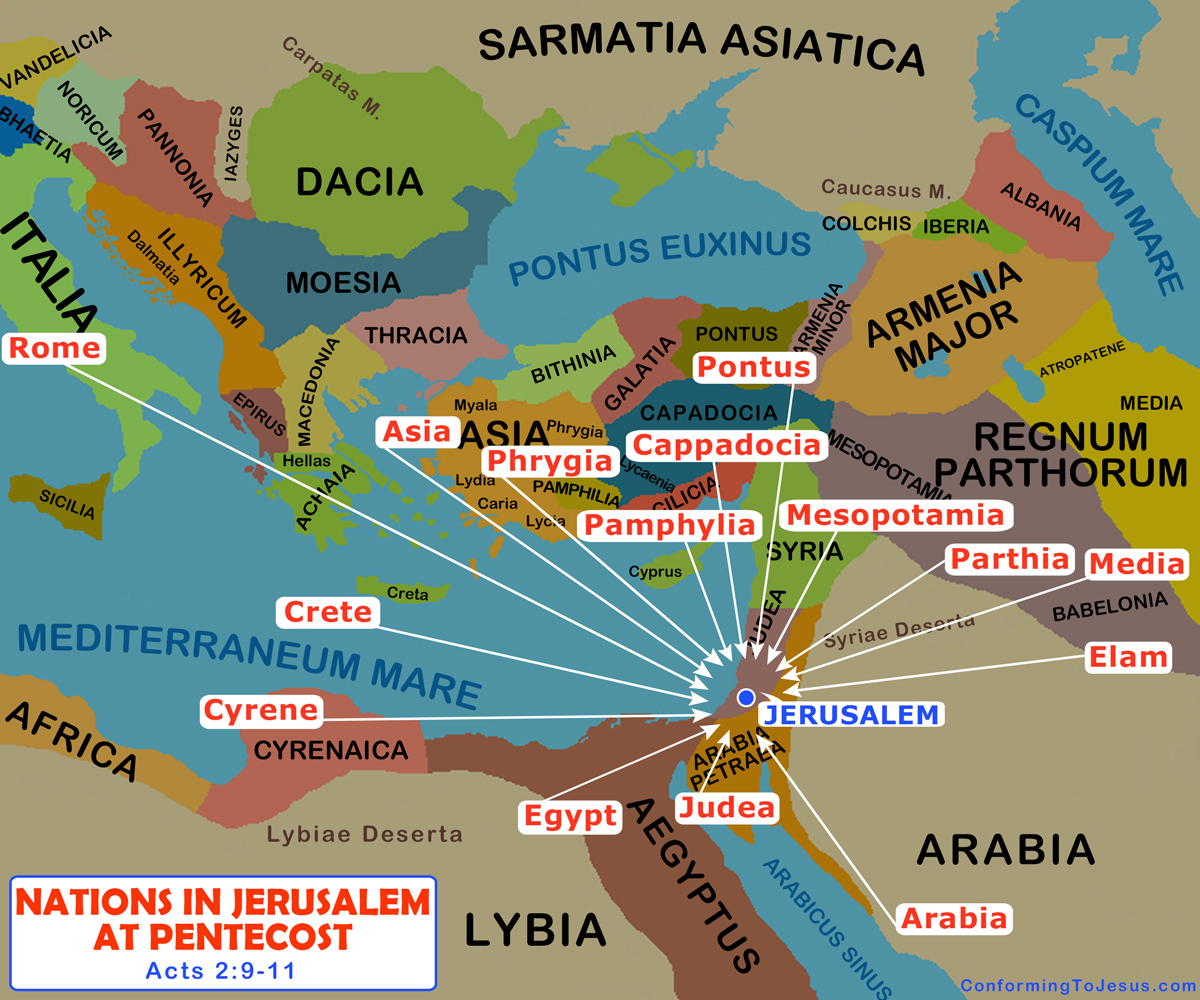

So, what does text criticism mean to Bible students who do not know the original languages, and so lack access to the many texts behind the text on the page? First, the King James should not be your go-to study Bible. The language of the King James is beautiful and poetic: more often than not, the passages I have committed to memory are from its pages! For its day, the King James was an excellent translation. However, quite apart from the fact that we no longer speak in King James English, the translators in 1611 simply lacked access to the many ancient texts now available. Indeed, the oldest Hebrew manuscripts extant, the so-called Dead Sea Scrolls from Qumran, were unknown before the mid-twentieth century. Sunday is Pentecost, which means that bewildered lay readers (and more than a few preachers!) across the church will once again be wrestling with the jawbreaking, tongue-tangling list of place names (go

Sunday is Pentecost, which means that bewildered lay readers (and more than a few preachers!) across the church will once again be wrestling with the jawbreaking, tongue-tangling list of place names (go  Meanwhile, Jesus’ followers were waiting in Jerusalem as he had commanded them (

Meanwhile, Jesus’ followers were waiting in Jerusalem as he had commanded them (

![Title: Prophet Miriam [Click for larger image view]](http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/miriam33172410852_bcf5c473db_k.jpg)

In the early church, when believers met in this holy season, they would greet one another with a hearty and enthusiastic Christe anesti–“Christ is risen!”–to which the only possible response is Allthos anesti–“He is risen indeed!”

In the early church, when believers met in this holy season, they would greet one another with a hearty and enthusiastic Christe anesti–“Christ is risen!”–to which the only possible response is Allthos anesti–“He is risen indeed!”

As we approached Jerusalem

As we approached Jerusalem

I am a lectionary preacher–a practice I commend as a way to break out of the hamster wheel of our favorite, comfortable passages and encounter the wideness–and wildness–of the Bible. But I confess that sometimes, the logic of the lectionary escapes me. The only reading from Zechariah in the Revised Common Lectionary is

I am a lectionary preacher–a practice I commend as a way to break out of the hamster wheel of our favorite, comfortable passages and encounter the wideness–and wildness–of the Bible. But I confess that sometimes, the logic of the lectionary escapes me. The only reading from Zechariah in the Revised Common Lectionary is  Both Matthew and John quote Zechariah 9:9 in their accounts of Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem (

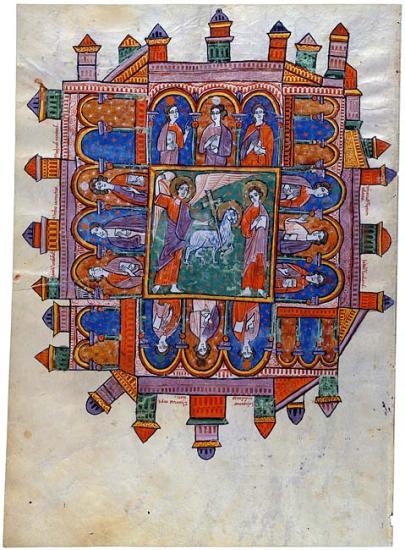

Both Matthew and John quote Zechariah 9:9 in their accounts of Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem ( As this unit unfolds, it continues to draw distinctions between this king and other, previous kings. Although the humble mount in 9:9 derives from a long tradition of kingly processions involving the king riding an ass (Meyers and Meyers 1993, 129), this passage surely catches the point of that tradition: by riding an ass rather than a war horse or chariot, the king shows humility, and declares that he comes in peace. Yet this time, the prophet declares, this is more than theater! This king truly is humble, and not only comes in peace, but comes to bring peace: a promise our war-torn world desperately needs to hear!

As this unit unfolds, it continues to draw distinctions between this king and other, previous kings. Although the humble mount in 9:9 derives from a long tradition of kingly processions involving the king riding an ass (Meyers and Meyers 1993, 129), this passage surely catches the point of that tradition: by riding an ass rather than a war horse or chariot, the king shows humility, and declares that he comes in peace. Yet this time, the prophet declares, this is more than theater! This king truly is humble, and not only comes in peace, but comes to bring peace: a promise our war-torn world desperately needs to hear!