![Title: David and Goliath [Click for larger image view]](https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/Swanson-David-and-Goliath.jpg)

The Old Testament reading for this Sunday is 1 Samuel 17:(1a, 4-11, 19-23), 32-49: the familiar story of David and Goliath. The painting above by folk artist John August Swanson is the way that I recall this scene from my childhood Bible story books. Goliath is a fairy-tale giant, inhumanly massive. Little David’s defeat of this monster is a nothing short of a miracle: especially as David eschews armor and weaponry, facing the giant with only his shepherd’s sling and five smooth stones. That is how we tell the story. But what does the Bible say? Just how big was Goliath, anyway?

In the old King James Bible, where I first read this story, his “height was six cubits and a span” (1 Samuel 17:4; see also the NRSV, the NIV, and the ESV)–a literal rendering of the Hebrew shesh ‘ammot wazareth. The Hebrew units were originally rules of thumb: a cubit is the distance from your elbow to the tip of your middle finger; a span is the width of your outstretched hand, from the tip of your thumb to the tip of your little finger–or, as you can check for yourself, about half a cubit. According to Kahler and Baumgartner’s Lexicon, that would be about a foot and eight inches (50 cm) for a cubit, and about ten inches (25 cm) for a span, making Goliath ten and a half feet tall! The CEB (and text critic P. Kyle McCarter in his HarperCollins Study Bible footnotes) presume a more conservative reckoning: “he was more than nine feet tall.” Now, that is big, to be sure, but it isn’t fairy-tale big: Goliath was not 25 feet tall, or 50 feet tall. He was much bigger than people usually get, but still a very big man, not a monster (although the marginal notes in one Latin text suggest that Goliath was sixteen cubits tall!).

Intriguingly, the Septuagint–the translation of Jewish Scripture into Greek from north Africa, in the century or two before Jesus’ birth–says that Goliath’s height was four cubits and a span, or (according to McCarter and the CEB footnotes), over six feet tall. This is still big–particularly in the Late Bronze-Early Iron Age, when (at five and a half feet) I would have been tall. But it is scarcely gigantic: most pro basketball centers (who average seven feet) would be taller than Goliath!

Sometimes, the differences between the Septuagint and the Hebrew text used in the synagogue, on which our Old Testament is based (called the Masoretic text, or MT) involve the translators re-interpreting or even misreading the text before them. But the discovery of ancient Hebrew scrolls and fragments at Qumran (commonly called the Dead Sea Scrolls) confirms that often, the Septuagint translators were working with different–and in many cases, older and better–texts of those books. This is particularly the case with Samuel, which seems to have been poorly preserved by the MT scribes. One fragmentary Hebrew text of Samuel, found in Cave Four (4Q Sam a), is now the oldest and best text of Samuel available. In 1 Samuel 17:4, it too reads four cubits and a span.

So, if Goliath was not a giant, but just a big man, why was no one in Saul’s army willing to face him in single combat? The text tells us why: Goliath was ‘ish-habbanayim–“the man who stands between” (English Bibles render this as “champion”). In other words, going out alone between combatting forces, to face and defeat the ish-habbanayim of his enemies in single combat, was Goliath’s job. That he was still alive, and famous, means that he was very good at his job. Goliath was a dangerous, well-trained, and well-armed professional killer.

To us, this too may sound like a fairy tale: would any army really rely on single combat to determine which side would prevail? We know that other clan-based cultures did use such contests to resolve their differences. The Celts, in particular, sometimes settled disputes over property or territory not only by single combat, but by non-lethal contests between bards involving song, poetry, and insults! Such resolutions would be far more economical than pitched battles, with their loss of life and destruction of property.

The description of Goliath’s armor and weaponry tells us much, both about the culture of the times, and this champion’s preferred fighting style:

He had a helmet of bronze on his head, and he was armed with a coat of mail; the weight of the coat was five thousand shekels [about 125 pounds] of bronze. He had greaves of bronze on his legs and a javelin of bronze slung between his shoulders. The shaft of his spear was like a weaver’s beam, and his spear’s head weighed six hundred shekels [about fifteen pounds] of iron; and his shield-bearer went before him.(1 Samuel 17:5-7, NRSV).

The mixture of bronze and iron in Goliath’s weaponry is a reminder of the late eleventh century BCE context of this narrative. The Philistines (unlike the Hebrews; see Judges 1:19) had mastered the working of iron, but it was still difficult, and expensive. So only the head of Goliath’s heavy, stabbing spear is made of that wonderful, armor-piercing metal; his armor, and his throwing javelin, are bronze (intriguingly, his sword is not mentioned). That javelin, note, is Goliath’s only distance weapon–which makes sense, for a single fighter. Goliath counts on closing with his enemy, where his size and strength–and his armor-piercing spear–will make short work of any adversary.

David’s chosen tactic, then, makes good sense! Being unarmored, he can move quickly: much more quickly than his heavily armored adversary. Should Goliath opt to throw his javelin, David will be able to dodge. Goliath, on the other hand, is anything but nimble: a scarcely-moving target for David’s sling stones. David’s sling catches him in the forehead, just below his bronze helmet, and knocks him senseless–so that David can run up and decapitate the Philistine champion with his own sword (1 Samuel 17:51).

![Title: Tapestry of David slaying Goliath [Click for larger image view]](https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/nat-cathedral-goliath.jpg)

This is a different story than the one in my childhood Bible story book! But I think it is a better one. Retelling the story, we tend to heighten the marvelous and miraculous elements, something that indeed the Bible does as well. Some biblical traditions do claim the the Israelites faced giants in Canaan–monsters descended from the half-human, half-god Nephilim (Numbers 13:33; Genesis 6:4). But the more human story revealed by the best text of Samuel does not in any way lessen God’s involvement and care. If anything, it makes the encounter between David and Goliath more real: less a children’s story about “Bible times” and more a promise of God’s presence with us in our encounters with enemies that seem too strong to overcome: whether the besetting sins that threaten our personal spiritual walk, or the national and cultural sins of racism, poverty, and pollution. With David, we can say to our contemporary adversaries,

You are coming against me with sword, spear, and scimitar, but I come against you in the name of the LORD of heavenly forces, the God of Israel’s army . . . the whole world will know that there is a God on Israel’s side. And all those gathered here will know that the LORD doesn’t save by means of sword and spear. The LORD owns this war, and he will hand all of you over to us (1 Samuel 17:45-47).

![Title: Lift Every Voice and Sing, or, The Harp

[Click for larger image view]](http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/lift-every-voice8927xc.jpg)

(now the ears of my ears awake and

(now the ears of my ears awake and

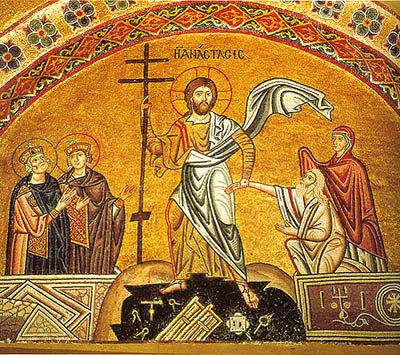

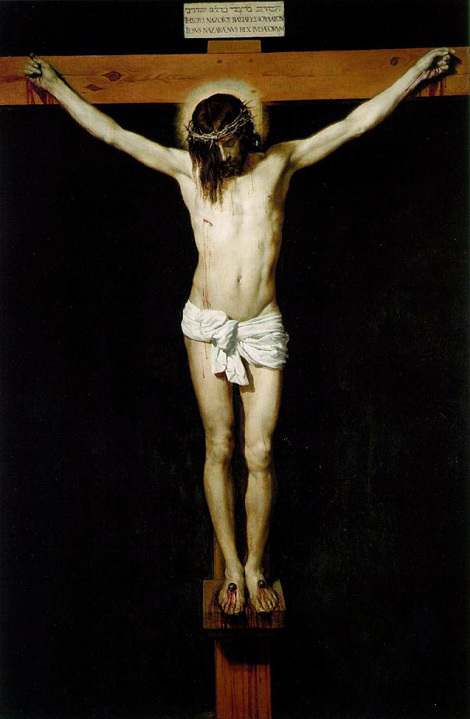

By around the eighth century, this confession was incorporated into the Apostles Creed; most Christians today recite the phrase “He descended into hell” or “He descended to the dead” as part of the Creed (although many

By around the eighth century, this confession was incorporated into the Apostles Creed; most Christians today recite the phrase “He descended into hell” or “He descended to the dead” as part of the Creed (although many

In

In

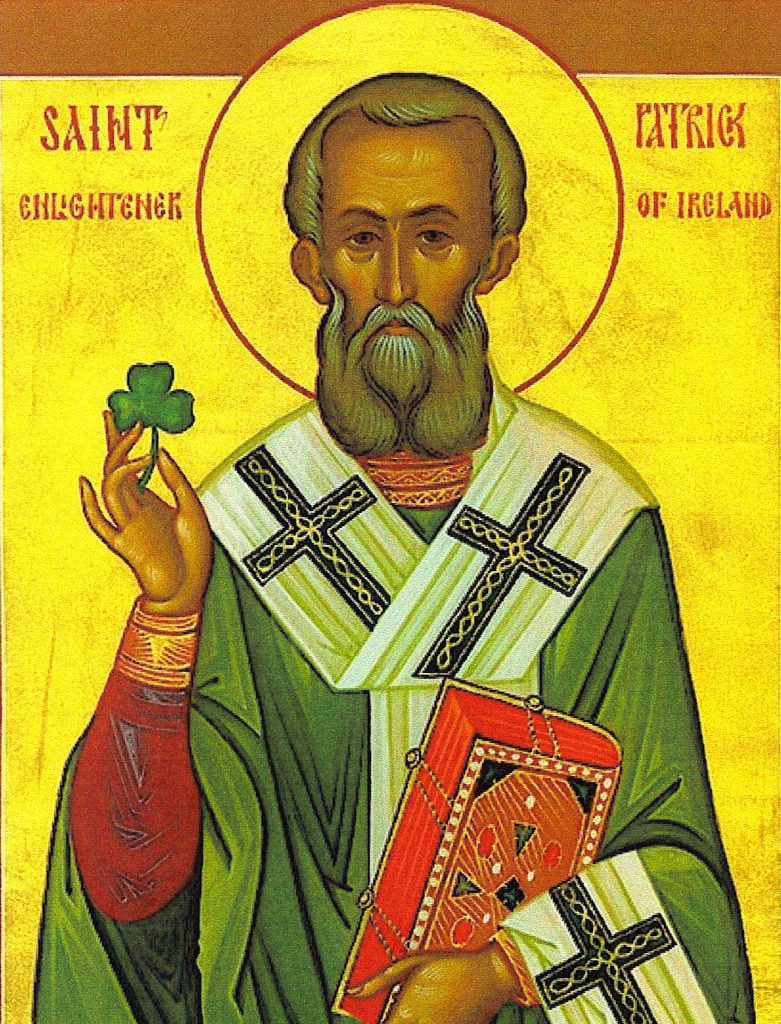

Patrick embraces a joyful spirituality of nature, wherein a simple herb expresses the mystery of God’s nature, the vibrancy and constancy of wind and water and stone and tree witness to God’s presence and power, and the line between the human world and the animal world, between people and deer, can blur and vanish. This St. Patrick’s Day, may we too seek God first, and so find fulfillment for ourselves and for God’s world.

Patrick embraces a joyful spirituality of nature, wherein a simple herb expresses the mystery of God’s nature, the vibrancy and constancy of wind and water and stone and tree witness to God’s presence and power, and the line between the human world and the animal world, between people and deer, can blur and vanish. This St. Patrick’s Day, may we too seek God first, and so find fulfillment for ourselves and for God’s world.