When I was a child, the question of which Bible I should read never arose. So far as I knew, there was only one Bible: the King James Version. I still hear in the back of my head the language of the King James in deeply familiar texts, and those passages which I have memorized are, as likely as not, recalled from this version.

Certainly, this common reference point had many advantages. English-speaking Christians (or at least, English-speaking Protestants!) all had and used the same Bible, so when I heard a preacher read or quote from Scripture, what he (and yes, in those days it was nearly always a “he”) said matched what I saw on the pages of my own Bible.

Of course, that is not so today! Go to any bookstore, and you will find dozens of different Bibles–not just different in binding or study notes, but different in content. How could that be?

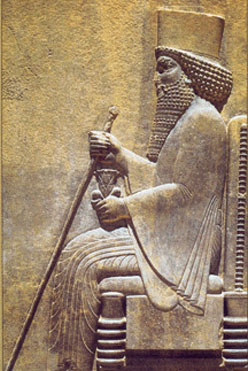

We know, of course, that the Bible was not written in English. The Old Testament, or Hebrew Bible, was written in Hebrew, primarily–the language of ancient Israel. Some parts, however, are written in another ancient language commonly used in the ancient Middle East: two words from Genesis 31:47, one verse from Jeremiah (10:11); the middle chapters of Daniel (2:4b–7:28); and some ancient documents cited in Ezra (4:8–6:18; 7:12-26) are written in Aramaic, the language of commerce and diplomacy in the ancient world, particularly in the Persian Period (539-333 BC).

The conquests of Alexander the Great (333-323 BC) spread Greek language and culture throughout the ancient Middle East. In the first and second centuries AD, when the books of our New Testament were written, Greek was the language used when cultures met, particularly for trade; as a result, nearly everyone spoke at least some Greek, in addition to their native language.

The Septuagint, a translation of the Jewish Scriptures into Greek, was written in the second and first centuries BC, in Egypt. The New Testament too was written in Greek–not the Greek of the poets and philosophers, but koine, or common, Greek: what we might call street Greek! In first-century Palestine, the native language was Aramaic (not, intriguingly, Hebrew, which had become the language of the synagogue and of scholars rather than the everyday language of the people), and there are some words and phrases of that language preserved in the New Testament as well. When Scripture was read aloud in synagogue, the reading would be followed by a Targum: a translation of the passage into Aramaic. In time, these too were written down and circulated among the Aramaic-speaking Jewish community.

Christians also translated the Bible into their native languages. The Vulgate, for example, put the Bible into the common or “vulgar” language of the Roman Empire, Latin.

The King James Version (KJV) of the Bible was translated in 1611; it has just celebrated its 400th birthday! We can scarcely overstate the importance of this translation for English language and culture. Together with the plays of Shakespeare, the KJV helped standardize rules for English spelling and usage, and gave English its basic, common vocabulary.

However, the English language has changed a lot since 1611. Not only are the “thees” and “thous” gone, but the meaning of some words has changed. For example, the KJV of 1 Corinthians 13, Paul’s famous Love Chapter, reads “charity” rather than “love” for the Greek agape: appropriate then, but misleading now, when “charity” has taken on a more narrow and restricted meaning. A more jarring is example is Mark 10:14, which in the KJV reads, “Suffer the little children to come unto me”! Jesus meant, of course, that the disciples should allow the children to come; “suffer” no longer means all that it did in 1611.

Further, we know more about language and translation than we did in 1611, and translators today have access to far more texts than they did (including, for many parts of the Hebrew Scriptures, the Dead Sea discoveries). One of many places where this makes a difference is 1 John 5:6-8. Here, the author of 1 John, referring to Jewish law requiring two or three witnesses for conviction (see Deuteronomy 17:6), declares that the testimony concerning Jesus is confirmed by three witnesses: the Spirit of God, the water (likely a reference to Jesus’ birth) and the blood (Jesus’ death on the cross). The KJV of 1 John 5:7-8 reads, however, “For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one. And there are three that bear witness in earth, the Spirit, and the water, and the blood: and these three agree in one.” This reference to the Trinity is not found in any Greek text of 1 John from before the 16th century, though it does appear in late texts of the Latin Vulgate. Almost certainly, this sentence does not belong to 1 John, but rather reflects later Christian reflection on the text.

It was for these reasons and more that Christians saw the need for new translations of the Bible into English. Next week, we will look at several English translations of the Bible, discussing their strengths and weaknesses.