I have been diving deeply into Daniel in recent days, prompted by an assignment for a textbook on the prophets I am writing with my good friends Steve Cook and John Strong, and by a Lenten series on Daniel I am teaching at Fox Chapel Presbyterian. Right now, I am thinking about the story of Belshazzar’s feast (Dan 5:1-31). Like the story of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego in the fiery furnace, or of Daniel in the lions’ den, Belshazzar’s feast is one of the best-known and most-loved stories in Scripture, familiar to many of us from when we were children in Sunday School or Vacation Bible School. Indeed our English expressions “the writing on the wall” and “weighed in the balances and found wanting” come from this narrative.

That Belshazzar used the gold and silver vessels stolen from Jerusalem’s temple for his drunken party (see Dan 1:2, which details the destruction of the temple and the theft of those vessels by Nebuchadnezzar) was bad enough. But then, Belshazzar and his guests further defiled all that remained of the holy temple, compounding disrespect with sacrilege: as they “drank a lot of wine,” they “praised the gods of gold, silver, bronze, iron, wood, and stone” (Dan 5:4). Belshazzar symbolically destroyed the temple all over again, sealing his own fate and the fate of his kingdom. Now at last judgment would come upon Babylon for the destruction of Jerusalem.

The judgment is announced formally, in writing, via a most unusual inscription: “the fingers of a human hand appeared and wrote on the plaster of the king’s palace wall in the light of the lamp” (Dan 5:5). None of the sages and magicians in Belshazzar’s court is able to interpret the strange writing. But then, the queen steps forward (Dan 5:10; given both her influence over Belshazzar and her clear knowledge of events from Nebuchadnezzar’s reign, she may be the king’s mother, or even grandmother, rather than his wife) to tell Belshazzar of Daniel’s great wisdom, derived from “the breath of holy gods” (Dan 5:11, see also 5:14 and 4:8)–or perhaps, from “the spirit of the holy God”!

The message, we now learn, reads, “MENE, MENE, TEKEL, and PARSIN” (Dan 5:25). These were common, familiar Aramaic words: units of weight and money equivalent to the Hebrew minah (about a pound in weight; in money, about four months wages), shekel (about a third of an ounce in weight; maybe $10.00 in modern currency–but note that the Israeli shekel today is worth about 29 cents US) and paras (half of a minah).

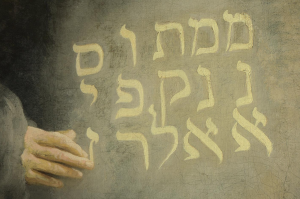

So, why does the text say that no one could understand the writing? Some have suggested that the writing was coded in some way. In his famous painting of this scene, Rembrandt depicts the words as written in columns, so that anyone trying to read the letters normally, in a line from right to left, would find nonsense:

So, why does the text say that no one could understand the writing? Some have suggested that the writing was coded in some way. In his famous painting of this scene, Rembrandt depicts the words as written in columns, so that anyone trying to read the letters normally, in a line from right to left, would find nonsense:

But nothing in our passage suggests a difficulty in reading the message. The problem wasn’t what this message said–that was clear enough! Although these amounts are of course WAY off, it is as though the writing on the wall read “A dollar, a dollar, a penny, and fifty cents.” We could read such a message with no problem, and know the meaning of each word, but still be left asking, “What the dickens does that mean?”

In Daniel’s interpretation, each Aramaic noun is read as a related (or at least, similar-sounding) verb, so that the message means “Numbered, numbered, weighed, and divided.” The application of this message to Belshazzar is now made painfully clear. “MENE: God has numbered the days of your rule. It’s over!” (Dan 5:26). The repetition intensifies this judgment—and indeed, according to Dan 5:30-31, Babylon fell that very night. “TEKEL means that you’ve been weighed on the scales, and you don’t measure up” (Dan 5:27)–or, in the classic language of the King James Version, “Thou art weighed in the balances, and art found wanting.” Not only the kingdom of Babylon, but Belshazzar himself personally, had been judged and condemned; Belshazzar died the same night that his kingdom fell. “PERES means your kingship is divided and given to the Medes and the Persians” (Dan 5:28). Here, we hit a problem.

The Babylonian empire was not, historically, divided between the Medes and Persians. It had been the Assyrian empire that was divided between the Medes and the Babylonians. In 612 BCE, the alliance of Cyaxares the Mede and Nabopolassar the Babylonian destroyed Nineveh, capital of the Assyrian Empire, and divided the Assyrian territory between them. The Median empire was contemporaneous with the Babylonian Empire, and fell to Cyrus the Persian in 549 BCE—seventeen years before Babylon was conquered. Why then does Daniel insist that the Medes followed the Babylonians, and preceded the Persians (see Dan 6:28)?

This is not the only historical snag in this narrative. The historical Belshazzar was neither the son of Nebuchadnezzar nor the last king of Babylon. Belshazzar’s actual father Nabonidus (556-539 BCE) was Babylon’s last ruler, and while Belshazzar ruled as regent during his father’s frequent absences from Babylon, he was never king. The city of Babylon fell to Cyrus the Persian (cf. 2 Chron 36:22-23; Ezra 1:1-4; Isaiah 45:1-4), not the otherwise unknown Darius the Mede credited with that conquest in Dan 5:30-31.

These factual glitches make sense when we realize that Daniel was not written at the time in which these stories are set. The community the book of Daniel directly addresses, and for whom it has been written, lived in the mid-second century BCE–as far removed from the Babylonian exile as we are from Shakespeare. For this community, the future history envisioned in Nebuchadnezzar’s dream (Dan 2) and Daniel’s vision of the four beasts (Dan 7) reached its culmination with them. There would be, these symbolic accounts declared, four great world kingdoms: the Babylonians, the Medes, the Persians, and then the fourth, and last, world kingdom–the Greek empire established by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE. When Daniel was written, their part of the Greek world, in Palestine, was ruled by the cruel despot Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175-164 BCE)–but not for much longer! Soon heavenly armies, led by the archangel Michael, would intervene:

At that time, Michael the great leader who guards your people will take his stand. It will be a difficult time—nothing like it has ever happened since nations first appeared. But at that time every one of your people who is found written in the scroll will be rescued. Many of those who sleep in the dusty land will wake up—some to eternal life, others to shame and eternal disgrace. Those skilled in wisdom will shine like the sky. Those who lead many to righteousness will shine like the stars forever and always (Dan 12:1-3).

Of course, the world did not end in the mid-second century BCE. Later Jewish and Christian readers identified Daniel’s fourth kingdom first with Rome (2 Esdras 12:10-12; Rev 17:9), then with other oppressive powers. The message was re-read, again and again, and applied to new situations.

In short, Daniel is neither an accurate historical account of Babylonian and Persian history, nor a reliable record of future history. But if Daniel is not accurate, doesn’t that mean that Daniel is not true? How, then, can we read it as Scripture?

Our problem comes in large measure from the post-Enlightenment view in the West that “truth” and “fact” are one and the same. A little reflection reveals the poverty of that assertion. Consider what matters most to you—your faith, your friendships, those you love, what you find beautiful, what brings you joy. Now, ask how you might go about establishing these claims as facts. How would you prove them, empirically: what evidence could you marshal? What tests could you use?

For example: I love my wife. How would I establish that, empirically? I could analyze my actions toward Wendy, but could those same actions not be performed if I were practicing a deception, and only pretending that I loved her? If I were a chemist or biologist, I could talk about glands and hormones and chemical reactions in my brain. If I were a sociologist or anthropologist, I might compare our marriage with others statistically, and determine the likelihood of our relationship enduring; or examine courtship rituals in Western cultures. None of this, however, has anything to do with what I mean when I tell Wendy that I love her, or how I feel when she says that she loves me.

Certainly we want to affirm as true much that we cannot demonstrate as fact. To put this more precisely, we realize that what we can demonstrate as fact does not adequately express what our values mean to us, as if love were reducible to bioelectrical impulses in the brain or hormones or social convention. Such oversimplifications fail to comprehend the tremendously complex world of human life and experience, wherein the whole cannot be reduced to the mere sum of its parts.

So, Daniel can be true even if it is not factual. How can we read it as Scripture? The story of the writing on the wall shows us how–not just for this book, but for all of Scripture. For what a text says may not be all that a text means–nor does it direct or determine how that passage of Scripture should be applied. What we need is what Daniel provided for the ill-fated Belshazzar and his court: careful, prayerful, Spirit-led interpretation.

Like the other stories of Daniel and his friends in the first six chapters of this book, the story of Belshazzar’s feast is an effective and artful narrative, remembered and retold for its lesson on the dangers of hubris, and its message of God’s ultimate control of history. Indeed, all of the Daniel traditions model hopeful, faithful living in difficult, even oppressive, circumstances. Mahatma Gandhi, who called Daniel “one of the greatest passive resisters that ever lived,” said:

When Daniel disregarded the laws of the Medes and Persians which offended his conscience, and meekly suffered the punishment for his disobedience, he offered satyagraha [nonviolent resistance; the term was coined by Gandhi] in its purest form (Cited by Daniel Smith-Christopher, in “The Book of Daniel: Introduction, Commentary, and Reflections,” NIB VII, [Nashville: Abingdon, 1996], 91).

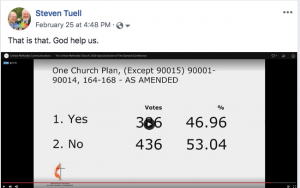

I find myself reading this passage today in light of the recent decision by the United Methodist General Conference not only to retain the language in our Discipline excluding lesbian and gay persons (“The United Methodist Church does not condone the practice of homosexuality and considers this practice incompatible with Christian teaching,” ¶ 161F), but to intensify enforcement, through church trials and penalties. Many at that gathering, as well as before and since, have presented this decision as affirming the “plain teaching of Scripture” on human sexuality, as set forth in Leviticus, Romans, and the Gospels, as well as in the Christian natural law tradition grounded in Genesis. The links given here will take you to my own studies of those passages. I freely acknowledge that what the Bible says, in some passages, condemns same-gender sexual relationships.

But we do not always follow the “plain teaching of Scripture” so unbendingly! Whatever our rhetoric, we generally recognize that there is not always a straight line from what Scripture says to what it means and how it is to be applied. Certainly in America, Christians have no difficulty insisting that the plain teachings of Jesus about money (e.g., Matt 6:4; 19:21) are not really about money, or that the New Testament’s condemnation of divorce and re-marriage (Matt 5:31-32; see also Matt 19:3-9//Mark 10:1-12 and Luke 16:18 and 1 Cor 7:10-16) does not apply to our marriages. Too often, we insist on taking a hard line with regard to the lives of others, while insisting on a gracious reading when the texts come too close to our own lives. “The authority of Scripture” too easily becomes a cover for my authority, my ideology, my preferred way of life.

How would it be, friends, if we came to Scripture the way that Daniel came to the message on Belshazzar’s wall–not assuming that we know what it says, or even that what it says expresses all that it means? How would it be if, guided by the “breath of our Holy God,” we permitted the Spirit to show us a new thing in this very old Book–to catch the Word of God within these ancient words?