Readings of the Eden story in Genesis 2:4b–3:24 often ignore an important theological concept: the idea of Eden itself, the center of the earth, on the true Mount Zion, from which its rivers flow to bring life to the whole earth. Within the Hebrew Bible, the identification of Eden with Zion is certainly implied in Isaiah’s famous “peaceable kingdom” texts, which imagine the mountain of God as an Edenic paradise (compare Isa 11:6-9; 65:17-25 and Gen 1:29-30). But in Ezekiel 28:11-19, a lament over the “king of Tyre” that concludes Ezekiel’s oracles against Tyre (Ezek 26:7—28:19), the identification of Zion with Eden is unambiguously made:

You were in Eden, the garden of God; every precious stone was your covering . . . On the day that you were created they were prepared. With an anointed cherub as guardian I placed you; you were on the holy mountain of God, you walked among the stones of fire (Ezek 28:13-14, NRSV).

“The holy mountain of God” (Ezek 28:14, 16; cf. 20:40) is certainly Zion, site of the Jerusalem temple. Yet Ezekiel calls this place “Eden.”

The association, and even the identification, of Zion and Eden is found in Second Temple and rabbinic texts as well. In 1 Enoch 25:3-5, the visionary sees the Tree of Life (Gen 2:9) planted on a beautiful mountain, situated among six other beautiful mountains in the northeast. The angelic interpreter Michael tells him,

This tall mountain which you saw whose summit resembles the throne of God is (indeed) his throne, on which the Holy and Great Lord of Glory, the Eternal King, will sit when he descends to visit the earth with goodness.

Zion is clearly the referent, so in this second- or third-century BCE apocalypse, Eden is Zion. On the other hand, in Jubilees 8:19, Eden and Zion remain distinct, although closely associated with one another:

And [Noah] knew that Eden was the holy of holies and the dwelling of the Lord. And Mount Sinai (was) in the midst of the desert and Mount Zion (was) in the midst of the navel of the earth. The three of these were created as holy places, facing each other.

Still, the concept of Zion as “the navel of the earth” also points toward a connection with Eden. As the center of the earth, Zion is the source of life and meaning for all creation.

There are several references in rabbinic literature to Zion as the navel of the world. Midrash Hashem Bekhokmah Yasad ‘Arets declares that the Lord created the world just as an embryo grows, from the navel outward. Another midrash, Tanhuma: Kedoshim 10, cites Ezek 38:12, which says that the people of Israel live ‘al-tabbur ha’arets: literally, “at the navel of the earth.” This demonstrates, according to the midrash, that Israel is the center of the world, just as the navel is the center of a human being. Little wonder, then, that according to Rabbi Eliezar the Great, creation began with Zion (b.Yoma 54b).

The importance of place in the Bible’s Eden/Zion traditions, and their notion of the center, is reminiscent of those same features in the primal religious traditions of indigenous peoples. Oglala Sioux author Vine Deloria, Jr. wrote:

The importance of place in the Bible’s Eden/Zion traditions, and their notion of the center, is reminiscent of those same features in the primal religious traditions of indigenous peoples. Oglala Sioux author Vine Deloria, Jr. wrote:

Thousands of years of occupancy on their lands taught tribal peoples the sacred landscapes for which they were responsible and gradually the structure of ceremonial reality became clear. . . . The vast majority of Indian tribal religions, therefore, have a sacred center at a particular place, be it a river, a mountain, a plateau, valley, or other natural feature. This center enables the people to look out along the four dimensions and locate their lands ( Vine Deloria, Jr., God Is Red: A Native View of Religion, 2nd ed [Golden, CO: Fulcrum, 1994], 67).

Cayuse leader Weatenatemany (“Young Chief”), when asked to sign a treaty in 1855 ceding land rights, replied, “I wonder if the ground has anything to say? I wonder if the ground is listening to what is said?”

Though I hear what the ground says. The ground says, It is the Great Spirit that placed me here. The Great Spirit tells me to take care of the Indians, to feed them aright. . . . The ground, the water and the grass say, The Great Spirit has given us our names. We have these names and hold these names. . . . The same way the ground says, It was from me man was made. The Great Spirit, in placing men on earth, desired them to take good care of the ground and to do each other no harm (cited in Touch the Earth: A Self-Portrait of Indian Existence, ed. T. C. McLuhan. NY: Promontory Press [reprint of Outerbridge & Dienstfrey], 1971, 8).

Such traditions preserve a sense of closeness and kinship with the natural world. In tension with the estrangement from the natural world evident in Gen 3:17, Chief Luther Standing Bear wrote in his autobiography,

We did not think of the great open plains, the beautiful rolling hills, and winding streams with tangled growth as ‘wild’ . . . Not until the hairy man from the east came and with brutal frenzy heaped injustices upon us and the families we loved was it ‘wild’ for us. When the very animals of the forest began fleeing from his approach, then it was that for us the ‘Wild West’ began (Luther Standing Bear, Land of the Spotted Eagle. New Edition. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska, 2006 [orig. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1933], 38).

For Chief Plenty Coups of the Crow, who died in 1932, the indiscriminate slaughter of the buffalo by white hunters marked the end of the world: “When the buffalo went away the hearts of my people fell to the ground, and they could not lift them up again. After this nothing happened.” In sharp contrast is the attitude of Native American hunters toward their prey, evident in the Navajo “Stalking Way:”

I am the Black God, arising with twilight,

a part of the twilight.

Out from the West, out from the Darkness

Mountain, a buck of dark flint stands out before me.

The best male game of darkness, it calls to me,

It hears my voice calling.

Our calls become one in beauty.

Our prayers become one in beauty.

As I, the Black God, go toward it.

As the male game of darkness comes toward me.

With beauty before us, we come together.

With beauty behind us, we come together.

That my arrow may free its sacred breath.

That my arrow may bring its death in beauty (Tony Hillerman, People of Darkness [New York: Harper & Row, 1980], 171).

Deloria proposed that the major difference between Native American and European world views is that, while indigenous peoples think in terms of place, Europeans think in terms of time: “American Indians hold their lands—places—as having the highest possible meaning . . . Immigrants review the movement of their ancestors across the continent as a steady progression of basically good events and experiences, thereby placing history—time—in the best possible light” (Deloria 1994, 62).

Hehaka Sapa, also known as Black Elk, was a famed shaman of the Oglala Sioux who became a Roman Catholic Christian. Regarding the Native American view of time, he wrote:

Everything the Power of the World does is done in a circle. The Sky is round and I have heard that the earth is round like a ball and so are all the stars. The Wind, in its greatest power, whirls. Birds make their nests in circles, for theirs is the same religion as ours. The sun comes forth and goes down again in a circle. The moon does the same, and both are round. Even the seasons form a great circle in their changing, and always come back again to where they were. The life of a man is a circle from childhood to childhood and so it is in everything where power moves (cited in McLuhan 1971, 42).

Preferencing time over space, Deloria argued, has led Christians to devalue the earth: “The idea of defining religious reality along temporal lines, therefore, is to adopt the pretense that the earth simply does not matter, that human affairs alone are important” (Deloria 1997, 70). Yet curiously, a major consequence of this loss of place is the dehumanization of ethical decision-making: ““Ethics seems to involve an abstract individual making clear, objective decisions that involve principles but not people. Ideology unleashed without being subjected to the critique to the real world proves demoniac at best.” By contrast, “Spatial thinking requires that ethical systems be related directly to the physical world and real human situations, not abstract principles, are believed to be valid at all times and under all circumstances” (Deloria 1997, 72).

How, Willie Jennings asks, has this loss of place affected Christian theology?

How does that removal of true speech, true sight regarding the materiality of the world affect a doctrine of creation? A Christian doctrine of creation is not dependent upon geographical precision; however, it is not wholly independent of geographical accuracy. Belief in creation has to refer to current real-world places or it refers to nothing (Willie James Jennings, The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race. [New Haven: Yale University, 2010], 85).

Jennings addresses this question historically, by examining the reasoning behind papal bull Romanus Pontifex, issued by Pope Nicholas V on January 8, 1455. This bull, which gave the prince of Portugal permission to enslave Africans and forcibly convert them to Catholicism, was based on a particular reading of Gen 1:1, specifically, the doctrine of creation ex nihilo (Jennings 2010, 27-28): “These actions inscribe the contingency of creation itself within the will and desire of the church and the colonial powers. The inherent instability of creation means all things may be altered to bring them to proper order toward saved existence” (Jennings 2010, 29).

Jennings persuasively argues that the loss of place in the Christian imagination has produced our ideas of race, for race becomes a “stand in for landscape in its facilitating characteristics,” a “substitution for place and place-centered identity” (Jennings 2010, 289). In this way, Jennings writes, “we have been transformed into racial identities. Our racial identities enfold imagined connections to land inside our individual bodies and construct racialized boundaries and racial kinship” (Jennings 2010, 289). Rather than building cross-cultural communities, learning from one another and celebrating our differences, we have built walls of isolation and exclusion.

Meanwhile, “colonialism established ways of life that drove an abiding wedge between land and peoples.”

Rather than a vision of a Creator arising through the hearing of Israel’s story bound to Jesus who enables peoples to discern the ways their cultural practices and stories both echo and contradict the divine claim on their lives, the vision born of colonialism articulated a Creator bent on eradicating people’s ways of life and turning the creation into private property (Jennings 2010, 292).

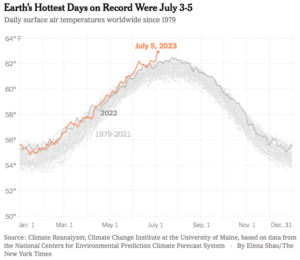

As I write this, we are experiencing record high temperatures worldwide; indeed many scientists are saying “The past three days [July 3-5, 2023] were quite likely the hottest in Earth’s modern history.” Runaway wildfires in Canada have resulted in visible smoke here in Pittsburgh, and difficult breathing conditions, particularly for children and the elderly. All reputable climatologists agree that our climate’s warming is human-driven, caused especially by the use of fossil fuels that have increased the proportion of heat-trapping “greenhouse gases” in our atmosphere, particularly carbon dioxide. Indeed, scientists at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory say that the current heat wave in the South and in northern Mexico, with its triple-digit heat index, is about 5 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than it would have been absent climate change.

Yet we do not even agree that there is a problem, let alone a solution! According to a 2014 survey conducted by the Public Religion Research Institute, “About one-quarter (23%) of Americans say that climate change is a crisis and 36% say it is a major problem, while nearly 4-in-10 Americans say climate change is a minor problem (23%) or not a problem at all (16%).” Sadly, a major predictor of climate change denial is being white and Christian: “White evangelical Protestants are more likely than any other religious group to be climate change Skeptics” (39%) and “are much more likely to attribute the severity of recent natural disasters to the biblical ‘end times’ (77%) than to climate change (49%).”

In a seminal 1967 article that gave birth to the ecological movement, historian Lynn White, Jr. placed the blame for “our ecological crisis” on Christianity: “the most anthropocentric religion the world has seen,” which “not only established a dualism of man and nature but also insisted it is God’s will that man exploit nature for his proper ends” (Lynn White, Jr., “The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis” Science 155 (1967): 1205).

White acknowledged the complexity of Christian faith, including views counter to those he had described:

The greatest spiritual revolutionary in Western history, Saint Francis, proposed what he thought was an alternative Christian view of nature and man’s relation to it: he tried to substitute the idea of the equality of all creatures, including man, for the idea of man’s limitless rule of creation. He failed (White 1967, 1207).

Still, White was persuaded that the crisis remained, at its root, a religious one, requiring (“whether we call it that or not”) a religious solution: “Both our present science and our present technology are so tinctured with orthodox Christian arrogance toward nature that no solution for our ecologic crisis can be expected from them alone. . . . We must rethink and refeel our nature and destiny” (White 1967, 1207).

For people of the Word, rethinking our nature and destiny begins with rereading our sacred texts, asking humbly what we may have missed, or gotten wrong. Jürgen Moltmann advocates a reading of Gen 1 whereby “the human being is the last being God created and therefore the most dependent of all God’s creations.”

For their life on earth, human beings are dependent on the existence of animals and plants, dirt and water, light, daytime and night-time, sun, moon, and stars, and without these things they cannot live. . . . The other creatures can all exist without the human being, but human beings cannot exist without them (Jürgen Moltmann, The Spirit of Hope: Theology for a World in Peril. Trans. Margaret Kohl and Brian McNeil [Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2019], 18).

Moltmann challenges us to

read the Bible not from the beginning but from the end. . . . The perfected creation does not lie behind us in a primal state, but ahead of us in a final one. We await the consummated creation and, together with the cosmos, we are now existing in its prehistory (Moltmann 2019, 66).

I remember as a boy singing an old Gospel hymn, “This world is not my home, I’m just a-passin’ thru. / My treasures are laid up somewhere beyond the blue. / The angels beckon me from heaven’s open door, / And I can’t feel at home in this world anymore.” But what if this world is my home, after all? What if salvation is not about escape from this world, but about God’s transformation of this world? Then, as Moltmann reminds us “Men and women will not be redeemed from transience and death from this earth, but together with the earth” (Moltmann 2019, 19). Then, we will seek to be a part of what God is doing, here and now, to bring in God’s kingdom. We will want to be found at our Lord’s coming doing those things that Jesus did among us: feeding people, healing people, freeing people, proclaiming the good news of God’s salvation and the completion of God’s creation.