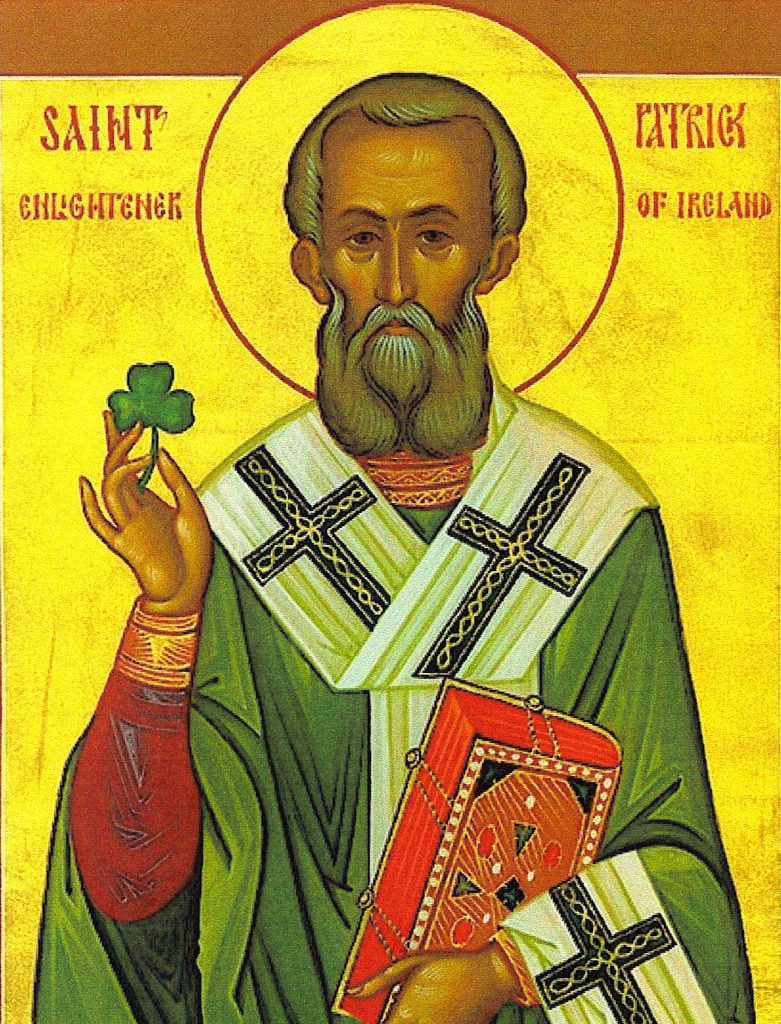

Friday March 17 is the feast of Saint Pádraig–better known as Patrick, patron saint of Ireland. St. Patrick’s teaching embraced God’s presence manifest in God’s creation–as in the tradition that Patrick used the shamrock to teach the Trinity. Of course, as a metaphor for God’s unity in three persons, the shamrock has its problems! But then again, perhaps every metaphor for the Divine life must fall short.

Friday March 17 is the feast of Saint Pádraig–better known as Patrick, patron saint of Ireland. St. Patrick’s teaching embraced God’s presence manifest in God’s creation–as in the tradition that Patrick used the shamrock to teach the Trinity. Of course, as a metaphor for God’s unity in three persons, the shamrock has its problems! But then again, perhaps every metaphor for the Divine life must fall short.

This week, I have been remembering the controversial depiction of the Trinity in William P. Young’s novel The Shack. My covenant group at St. Paul’s UMC read this book, but I honestly do not believe I ever finished it. Wendy reminds me that I was dismissive of The Shack, scornful of what I saw as its naïveté and its theological shortcomings.

This week, I have been remembering the controversial depiction of the Trinity in William P. Young’s novel The Shack. My covenant group at St. Paul’s UMC read this book, but I honestly do not believe I ever finished it. Wendy reminds me that I was dismissive of The Shack, scornful of what I saw as its naïveté and its theological shortcomings.

Then, on March 9, 2017, I went to see the film version with my father and my sister—and I wept. The film is visually beautiful, and, I thought, very well acted: especially by the lead Sam Worthington, and by the luminous Octavia Spencer as the First Person of the Trinity. I will freely allow that I was emotionally open and vulnerable, seeing this film with my father and sister on my late mother’s birthday, just a week before the first anniversary of her death. But mainly, I think, I was moved by the film’s potent portrayal of the boundless love of God, and the power of forgiveness.

In the movie as in the book, Mack Phillips has suffered a terrible tragedy. The loss of a child has plunged him, and his family, into darkness and despair. Led by a mysterious note to the eponymous shack, the place where his child had died, Mack is met by two women—a motherly African American cook and an Asian gardener—and by a young man, a Palestinian carpenter.

The three strangers reveal themselves as the triune Godhead, who teaches Mack about forgiveness, the major theme of this film: both the joy of being forgiven, and the freedom from anger and bitterness that comes when we forgive others.

The film, like the book, was harshly critiqued. Blogger Grayson Gilbert wrote,

The Shack panders to the sensationalism brought on by emotional appeal and subjective relativism. . . . If you want to hear from God, open up the scriptures and read. Drink deeply of a brook that never runs dry; fill yourself with waters free from the bitter gall of heretical teaching.

Pastor Jack Wellman concluded,

Even though The Shack is fiction, I believe it is dangerous, particularly for new Christians, because they don’t have enough knowledge of the Bible and of God, and so they might confuse these fictional characters with the way God really is. . . . I don’t need another fictional book to tell me what God is like. We have the best source on earth for that and its call [sic.] the Bible. We don’t have to guess about the nature of God or His attributes, because we can know.

Yet on the other hand, scholar Allan R. Bevere wrote,

I love reading theology. I enjoy parsing terminology and honing the sharp edges of doctrine into something finely tuned and precise. But I also enjoy reading the imaginative narratives that help me think theologically about life and faith in ways I had never considered. I am an unapologetic Nicene-Chalcedonian Trinitarian theologian; and I applaud Paul Young for his portrayal of the Trinity and his narrative display of some of our most significant beliefs and convictions in The Shack.

I wonder how much of the fury directed at The Shack really boils down to Wellman’s angry assertion, “the Father is not an African American woman and the Holy Spirit is not a mysterious Asian woman named Sarayu.” Reading this retort, I found myself thinking, “No, but neither is God an unjust judge (Luke 18:1-8), nor Jesus a thief (1 Thessalonians 5:1-4), nor the Holy Spirit a dove (Luke 3:22).” Scripture is filled with metaphors; indeed all of our language about God, without exception, is metaphorical. How could it possibly be otherwise, God being GOD, after all, and not an object in the world of space and time?

In a column on faith in the 21st century West, David Brooks argues for a “friendship with complexity” that engages the world, rather than an ideological purity that rejects it. Brooks concludes that the real enemy of faith is “a form of purism that can’t tolerate difference because it can’t humbly accept the mystery of truth.” How winsome can our faith possibly be if it is so rigid, pedantic, pedestrian, and rule-bound? What room can there be in such confining doctrinal boxes for a vibrant relationship with the living Lord?

What, after all, does the Bible say about the Trinity? The truth is–not much! Indeed, it would be generations before Christians refined their theology into the Trinitarian formulas in the classical creeds of the church. Christianity’s first ecumenical council, the Council of Nicaea, met in 325 CE. Particularly at issue for this gathering was how to speak meaningfully about the relationship between the Father and the Son. According to Arius and his followers, Jesus was a creation of God–the highest creature to be sure, indeed the first-born of all creation, but still distinct from the one God. Jesus and God are therefore homoiousias: of like substance or essence.

To be fair, this kind of language is used in Scripture. Colossians 1:15 describes Jesus as “the image of the invisible God, the one who is first [Greek prototokos, “firstborn“] over all creation.” The Christ hymn in Philippians 2:6-11 says that

Though he was in the form of God,

he did not consider being equal with God something to exploit.

But he emptied himself

by taking the form of a slave

and by becoming like human beings (Phil 2:6-7).

The Council, however, wound up affirming that Jesus and God were homoousias: that is, of the same substance, or of one substance. The Nicene Creed accordingly confesses,

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ,

the only Son of God,

eternally begotten of the Father,

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made,

of one Being [Greek homoousion] with the Father.

Through him all things were made.

So, why did the Council at Nicaea insist upon this confession? Theologian George Lindbeck has argued that Trinitarian theology grows out of the struggle of early Christians to speak plainly about their experience of God. Early on, the first Christians needed to affirm, on the one hand, the continuity of their faith with the faith of ancient Israel: the God they loved and worshipped was Abraham’s God. But at the same time, they needed to speak of Jesus in the most exalted language possible (what Lindbeck terms “Christological maximalism”), as they had come to know God, intimately and personally, through him. Hence, the New Testament calls Jesus God’s Son (The Nature of Doctrine [Nashville: Westminster John Knox, 1984], 94).

While full-blown Trinitarian language is wanting in the texts of Scripture, the Gospel of John comes very close. John 1:1 affirms,

While full-blown Trinitarian language is wanting in the texts of Scripture, the Gospel of John comes very close. John 1:1 affirms,

In the beginning was the Word

and the Word was with God

and the Word was God.

Indeed, in John 10:30, Jesus proclaims, “I and the Father are one.” In John 16:14-15, Jesus speaks of the Spirit who “will take what is mine and proclaim it to you” (16:14), yet also says “Everything that the Father has is mine” (16:15). Jesus, the Spirit, and the Father are distinct, yet intimately related.

This language in turn reflects the struggle of the sages of ancient Israel to find a way of talking about God as, on the one hand, separate from the world and its objects, and on the other, as intimately involved and engaged with the world. Particularly in Proverbs 8, they described divine Wisdom itself as a person: a woman, as the Hebrew word for Wisdom (khokmah) is feminine.

This language in turn reflects the struggle of the sages of ancient Israel to find a way of talking about God as, on the one hand, separate from the world and its objects, and on the other, as intimately involved and engaged with the world. Particularly in Proverbs 8, they described divine Wisdom itself as a person: a woman, as the Hebrew word for Wisdom (khokmah) is feminine.

Lady Wisdom says, “The LORD created me [Hebrew qanani; perhaps better “acquired me,” that is, as a wife] at the beginning of his way, before his deeds long in the past” (Proverbs 8:22). Through Wisdom, God creates a world reflecting God’s own character and identity: a community, a web of interrelationships, every part working together and responding to every other part, on every level.

Lady Wisdom says, “The LORD created me [Hebrew qanani; perhaps better “acquired me,” that is, as a wife] at the beginning of his way, before his deeds long in the past” (Proverbs 8:22). Through Wisdom, God creates a world reflecting God’s own character and identity: a community, a web of interrelationships, every part working together and responding to every other part, on every level.

I was formed in ancient times,

at the beginning, before the earth was.

When there were no watery depths, I was brought forth,

when there were no springs flowing with water.

Before the mountains were settled,

before the hills, I was brought forth;

before God made the earth and the fields

or the first of the dry land.

I was there when he established the heavens,

when he marked out the horizon on the deep sea,

when he thickened the clouds above,

when he secured the fountains of the deep,

when he set a limit for the sea,

so the water couldn’t go beyond his command,

when he marked out the earth’s foundations.

I was beside him as a master of crafts.

I was having fun,

smiling before him all the time,

frolicking with his inhabited earth

and delighting in the human race (Prov 8:23-31).

Christian readers will be reminded, again, of John 1:1-3:

In the beginning was the Word

and the Word was with God

and the Word was God.

The Word was with God in the beginning.

Everything came into being through the Word,

and without the Word

nothing came into being.

Here, Christ is the Word of God who is God, through whom the world was made. This is a Wisdom Christology: a way of talking about Christ drawn from the language of Proverbs 8!

1 John 4:8 gives us another way to visualize the Divine life: “God is love.” The greatest power in the universe is self-giving, sacrificial love! God in Godself is at once the Lover, and the Beloved, and the Love that binds them as one. God in Godself is relationship, and community!

Psychoanalytical pioneer and scholar of religion Carl Jung remembered taking confirmation classes from his father, a Lutheran minister. It was all very boring–but young Carl had read ahead in his catechism, and knew that coming up was something strange, mysterious, and wonderful–the Trinity! When the day assigned to study the Trinity arrived at last, however, Jung’s father said, “This is very complicated, and I really don’t understand it myself, so we’ll skip over it.” For Jung, this marked a major turning point, in his strained relationship with his father, and in his decision that he could not accept what he saw as his father’s pallid, shallow faith.

The Trinity is foundational for Christians in the most basic sense: we are baptized in name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit (Matt 28:18-20). So we really can’t “skip over” this. As the Council at Nicaea affirmed, it is true that God is three Persons, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit; yet it is also true that God is one. That may seem nonsensical–but the Trinity is not a logic problem for us to solve! We come to the paradoxical language of Trinity because we are driven to it by the shape of our experience of God. The doctrine of the Trinity emerges out of our struggle to talk meaningfully about who God is, and what God is up to in our world. As my friend and colleague from graduate school Ray Jones used to say about the Trinity, “I don’t believe this stuff because I want to. I believe it because it’s true!”

AFTERWORD:

“St. Patrick’s Breastplate” is a classic expression of Celtic spirituality (perhaps best known from this familiar hymn), and a full-throated celebration of the Triune God. Here is the prayer in full, translated into English verse by Cecil Frances Alexander in 1889:

I arise today

Through a mighty strength, the invocation of the Trinity,

Through belief in the Threeness,

Through confession of the Oneness

of the Creator of creation.

I arise today

Through the strength of Christ’s birth with His baptism,

Through the strength of His crucifixion with His burial,

Through the strength of His resurrection with His ascension,

Through the strength of His descent for the judgment of doom.

I arise today

Through the strength of the love of cherubim,

In the obedience of angels,

In the service of archangels,

In the hope of resurrection to meet with reward,

In the prayers of patriarchs,

In the predictions of prophets,

In the preaching of apostles,

In the faith of confessors,

In the innocence of holy virgins,

In the deeds of righteous men.

I arise today, through

The strength of heaven,

The light of the sun,

The radiance of the moon,

The splendor of fire,

The speed of lightning,

The swiftness of wind,

The depth of the sea,

The stability of the earth,

The firmness of rock.

I arise today, through

God’s strength to pilot me,

God’s might to uphold me,

God’s wisdom to guide me,

God’s eye to look before me,

God’s ear to hear me,

God’s word to speak for me,

God’s hand to guard me,

God’s shield to protect me,

God’s host to save me

From snares of devils,

From temptation of vices,

From everyone who shall wish me ill,

afar and near.

I summon today

All these powers between me and those evils,

Against every cruel and merciless power

that may oppose my body and soul,

Against incantations of false prophets,

Against black laws of pagandom,

Against false laws of heretics,

Against craft of idolatry,

Against spells of witches and smiths and wizards,

Against every knowledge that corrupts man’s body and soul;

Christ to shield me today

Against poison, against burning,

Against drowning, against wounding,

So that there may come to me an abundance of reward.

Christ with me,

Christ before me,

Christ behind me,

Christ in me,

Christ beneath me,

Christ above me,

Christ on my right,

Christ on my left,

Christ when I lie down,

Christ when I sit down,

Christ when I arise,

Christ in the heart of every man who thinks of me,

Christ in the mouth of everyone who speaks of me,

Christ in every eye that sees me,

Christ in every ear that hears me.

I arise today

Through a mighty strength, the invocation of the Trinity,

Through belief in the Threeness,

Through confession of the Oneness

of the Creator of creation.

Beannachtai Na Feile Padraig Oraibh, friends–May the blessing of St. Patrick’s Day be upon you!