FOREWORD: HEBREW GEEK ALERT! This blog goes pretty far into the weeds of Hebrew translation and text criticism–feel free to skim it, or even skip it if you must! Still, I have tried to make this post accessible to non-specialists, who I believe do need to have at least some awareness of these issues to read difficult texts, such as Ezek 28:11-19, knowledgeably. I hope this post proves useful to you. God bless you, friends!

By and large, working with the still new New Revised Standard Version, Updated Edition (NRSVue) of the Bible has been fairly seamless. Reviewing this revision of the NRSV (it is quite deliberately not described as a fresh translation), I earlier wrote:

While the RSV remains available, the editors have chosen to let the NRSV go out of print (so, for example, it is no longer available at the Bible Gateway website). I think this decision is unfortunate: I am certain that, as I use this new Bible, I will find still other places where I prefer the text critical decisions made in that earlier version to those in the NRSVue. Still, so far as I can now see, in most places the Updated Edition has stayed with the critical assessments of the NRSV, which is all to the good.

I recently encountered a fresh surprise in (and disagreement with!) this fresh revision. In my most recent Bible Guy blog, I wrote that in his lament over the “king of Tyre” (Ezek 28:11-19), the prophet Ezekiel identifies Eden with Zion. In the NRSVue, the relevant verses read “You were in Eden, the garden of God. . . I placed you on the holy mountain of God” (Ezek 28:13, 14). But elsewhere in their version of Ezekiel’s lament the editors of the NRSVue have made significant changes from the NRSV:

You were a cherub;

I placed you on the holy mountain of God;

you walked among the stones of fire.

You were blameless in your ways

from the day that you were created,

until iniquity was found in you.

In the abundance of your trade

you were filled with violence, and you sinned,

so I cast you as a profane thing from the mountain of God,

and I drove you out, O guardian cherub,

from among the stones of fire (Ezek 28:14-16).

Through these same verses, the NRSV, largely staying with the RSV, reads,

With an anointed cherub as guardian I placed you;

you were on the holy mountain of God;

you walked among the stones of fire .

You were blameless in your ways

from the day you were created,

until iniquity was found in you.

In the abundance of your trade

you were filled with violence, and you sinned;

so I cast you as a profane thing from the mountain of God,

and the guardian cherub drove you out

from among the stones of fire.

Note in particular the highlighted differences between “With an anointed cherub as guardian I placed you . . . and the guardian cherub drove you out” (Ezek 28:14, 16, NRSV, compare RSV) and “You were a cherub . . . and I drove you out, O guardian cherub” (Ezek 28:14, 16, NRSVue), which entirely change the meaning of the passage! For the record, the NRSVue follows here a similar approach to the CEB, the KJV, the NIV, and the ESV, as well as the Latin Vulgate. But before we deal with the reasons the NRSV team made different (but I will argue, better) text critical decisions, we need first to know what a cherub is!

At the head of this blog, you will find the image that likely comes to the mind of most readers when they see or hear the word “cherub”–a chubby little baby with wings! We describe adorable toddlers as “cherubic,” and many churches call their preschool music program the “cherub choir.” According to the Oxford English Dictionary, that use of “cherub” and “cherubic” goes back to 18th century England.

But in the Bible, cherubs (Hebrew kherubim) are terrible guardian spirits: bizarre semi-divine heavenly beings, represented elsewhere in the ancient Near East as winged sphinxes. The golden lid of the Ark of the Covenant was molded in the image of two kherubim, their wings overlapping to form a seat (Exod 37:1-9)–a cherub throne, as the divine title “the LORD, who is enthroned on the cherubim” indicates (for example, 1 Sam 4:4; Ps 80:1).

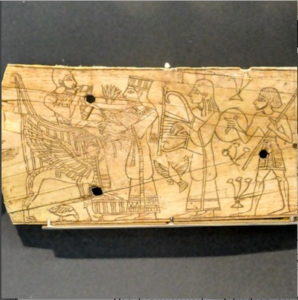

This detail of a 13-14th century BCE ivory plaque from Megiddo depicts such a cherub throne. In Solomon’s temple, the Most Holy Place held a massive one: two cherubim stood side by side facing the main chamber of the temple with their inner wings touching, overshadowing the ark, and their outer wings stretching out to the chamber walls. (1 Kgs. 6:19–28//2 Chr. 3:8–13). However, the throne was empty–the LORD was believed to be enthroned invisibly above the cherubim. The Ark itself thus served as the LORD’s footstool, making it the intersection of divine and human worlds, and the place of the LORD’s special presence.

Returning to the NRSVue of Ezekiel’s poem: it must be said that this revision faithfully adheres to the Masoretic text of the Hebrew Bible used in the synagogue, upon which our Old Testament is based. Ezekiel 28:14 does read ‘att-kherub, “you were a cherub,” and 28:16 reads wa’abbedka kerub-hassokek, “I drove you out [i.e., “to be destroyed”], guardian cherub.” By this reading, Ezekiel compares the imminent fall of the proud king of Tyre to the fall of an angel/cherub from heaven.

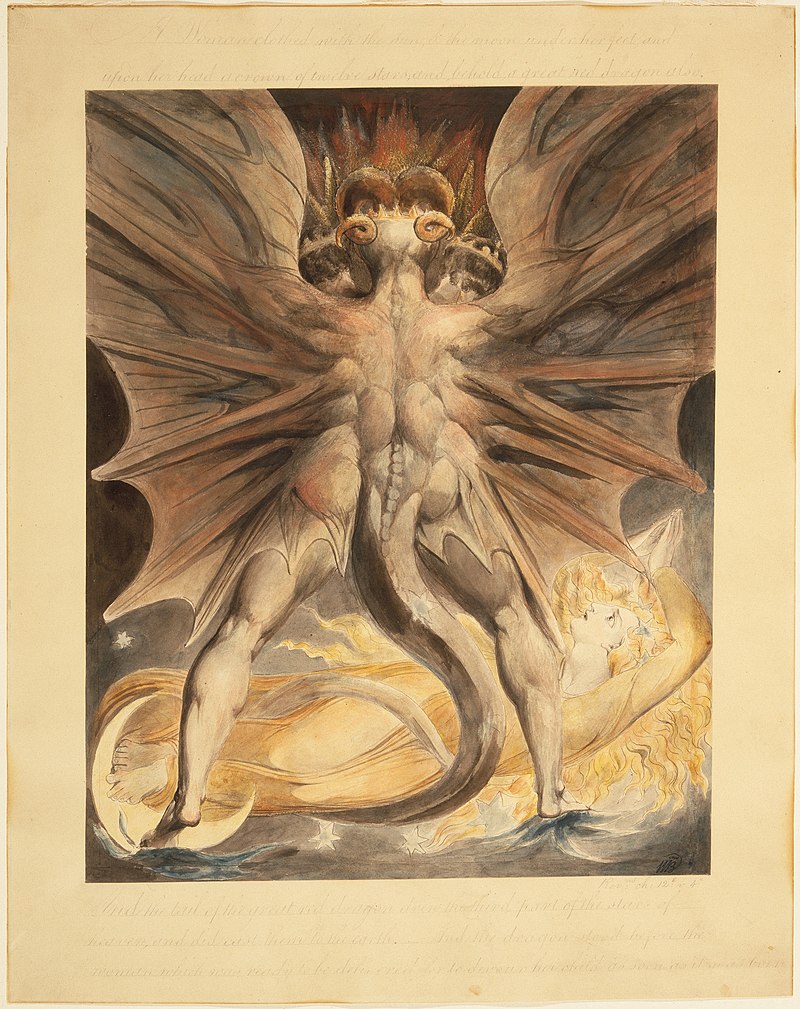

Traditional Christian interpretations read Ezek 28:11-19 together with Isa 14:3-23, a taunt song directed against the king of Babylon which alludes to the fall from heaven of helel ben-shakhar, “morning star, son of dawn” (Isa 14:12). Both passages are believed to describe the fall of Satan (the name “Lucifer,” or Light-bearer, is derived from Isa 14:12 in the Vulgate). So Tertullian cited Ezek 28 as proof that Satan was created good, but became corrupt through his own choices (Adversus Marcionem 2.10), while Theodoret of Cyrus wrote, “Forcing the text, someone might apply these things even to the historical prince of Tyre, but the text truly and properly corresponds to that demon which produces sinfulness” (Comm. Ezek 28).

Marvin Pope proposed that both Isaiah and Ezekiel referred to the fall of the Canaanite god El, displaced by the vigorous young storm god Baal (depicted above)—a story not told outright in the Ugaritic sources, but reconstructed indirectly (Marvin Pope, El in the Ugaritic Texts [Leiden: Brill, 1955], 97-103). A more likely parallel for Isa 14:3-23 is the Canaanite myth of Athtar, an astral figure who claimed Baal’s throne for a brief time before being expelled from the heavens for his overweening pride and audacity (KTU 1.6 i; see W. G. E. Watson, “HELEL,” in Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, Second Edition, Extensively Revised, eds. Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, and Pieter W. van der Horst [Leiden: Brill, 1999], 393).

But there are problems with the NRSVue’s rendition of Ezekiel 28:11-19, and with the “fall from heaven” interpretation of the passage as well. In Ezek 28:14, the Greek Septuagint (LXX) reads meta tou cheroub (“with the cherub”), which presupposes not the ‘att-kherub of the Masoretic text (“you were a cherub”) but ‘eth-kherub (“with a cherub”), a reading also found in the Syriac translation.

Remember that Hebrew was originally written with consonants only. In the Masoretic Text (MT) of our Hebrew Bible, scribal families called the Masoretes have added a system of marks above, below, and even within the consonants to record what they heard when the text was read aloud. This included not only the vowel sounds, but also the voicing of the consonants (as well as doubled letters in spelling), rising and falling inflections, and pauses.

The consonantal text (את־חרוב) is the same for both ‘att-kherub in the Masoretic text (“you [were] a cherub”) and ‘eth-kherub, assumed by the LXX (“with a cherub”). But in support of the LXX and the Syriac traditions, it must be noted that ‘att is the feminine form of the pronoun “you,” unlikely to be used either for the king of Tyre or the masculine noun kherub. The NRSV chose rightly, then, to follow the LXX and Syriac rather than the MT, and read “With an anointed cherub as guardian I placed you.”

Similarly, in Ezek 28:16, the LXX kai egagen se (“and he led you away”) apparently reads the consonants ואבדך not (with MT) as wa’abbedka, the first person preterite (simple past tense) of the verb אבד (“and I destroyed you/drove you [i.e., the cherub] out”), but as we’ibbadka, the third person perfect tense: “and he [i.e., the cherub] drove you out,” with the cherub as the subject, not the object, of the verb.

Two features of Hebrew support the LXX reading. First, in Hebrew syntax, the subject usually follows the verb: so we’ibbadka kherub hassokek would naturally mean “the guardian cherub drove you out” (with the NRSV). Second, definite direct objects are typically marked in Hebrew by ‘eth, so if the cherub was the object rather than the subject of the verb, we might expect ‘eth-kherub (we do find definite objects marked elsewhere in the Tyre oracles: see 26:4, 11; 27:5, 26; 28:6).

Since the consonantal text of Ezekiel 28 permits both the Masoretic and the LXX interpretations (with different pointing), we can legitimately ask which reading best explains the other. Here, the LXX arguably represents a more natural reading than the MT. Probably, then, the cherub is a supporting character in this drama after all, rather than the lead. The NRSV, rather than the NRSVue, best represents the meaning of this passage.

![]()

The mention of Eden in Ezek 28:13, together with the “guardian cherub” expelling the addressee of Ezekiel’s lament from that garden in Ezek 28:16, suggests to many readers that Ezek 28:11-19 is a retelling of the Garden story in Genesis 3, or perhaps even its source. By this reading, the fall of the king of Tyre is compared to the fall of the primal human. Such an interpretation certainly appears convincing. After all, the lament declares, “You were in Eden, the garden of God” (Ezek 28:13). The list of precious stones in that same verse brings to mind the wealth associated with the rivers of Eden in Genesis 2:10-14. Further, the lament goes on to describe the expulsion of its protagonist from Eden for the sin of pride, and specifically, for desiring forbidden wisdom (Ezek 28:17; compare Gen 2:17; 3:1-6). In both stories, a cherub seems to enforce the sentence of expulsion (Ezek 28:14, 16; compare Gen 3:24).

But many features of the narrative in Ezek 28 do not fit the Genesis Garden Story. The protagonist in Ezekiel’s lament is expelled from Eden, not simply for pride or seeking forbidden wisdom, but for unjust trade practices and violence (Ezek 28:16, 18). Indeed, many aspects of Ezek 28:11-19 do not fit its alleged target, the “king of Tyre,” either. Among the accusations raised against the “king of Tyre” is “you profaned your sanctuaries” (Ezek 28:18). What could this possibly mean, applied to the king of a foreign city? The language used for the expulsion of the “king of Tyre” is also odd: God declares, “I will cast you as a profane thing from the mountain of God” (Ezek 28:16). The verb used here, khalal, appears predominantly in Ezekiel (23 times) and in Leviticus (14 times), where it is used for the profanation or desacralizing of a person or thing (for example, Lev 21:12; Ezek 7:21). A better rendering of Ezek 28:16, then, would be “I will deconsecrate you”—language more appropriate for defrocking a priest than for removing a king from power.

Once the referent of the lament has been identified as the high priest in Jerusalem rather than the “king of Tyre,” solutions to numerous difficulties in this passage fall into place. The use of khalal (“profane”) for the “expulsion” of this figure makes far better sense if the passage describes the defrocking of a priest rather than the deposition of a king. It also makes perfect sense for priests to be castigated for defiling their sanctuaries; indeed, Ezekiel elsewhere accuses them of this very offense (Ezek 23:38-39). Nor is priestly involvement in violence and dishonest trade any surprise (Mal 1:6-8, and in the NT, Matt 21:12-13; Mark 11:15-17; Luke 19:45-46; John 2:14-22).

Which returns us, once more, to Ezekiel’s cherub! To understand the role that the cherub plays in this poem, we need to ask about the meaning of another word: the Hebrew sokek , rendered “guardian” in both the NRSV and the NRSVue of Ezek 28:16 (see also Ezek 28:14, where the NRSVue follows the LXX and skips over mimshakh hassokek [“anointed as guardian”?]). However, sokek is never used for a guardian anywhere else in the Hebrew Bible. It is used, however, for the cherub’s wings overshadowing the Ark (Exod 25:20; 37:9; 1 Kgs 8:7; 1 Chron 28:18), So the JPSV of Ezek 28 speaks rather of the “shielding” cherub, while the KJV reads “covering.” Both translations depict the function of the cherubim in the Temple, rather than the guard duty performed by the cherub in Gen 3:24. But that protection of the sanctity of Temple and Ark makes the temple kherubim the natural instruments of God’s judgment upon Jerusalem’s corrupt priesthood.

Robert Wilson argues that Ezek 28:11-19 is “a dirge which was ostensibly concerned with the king of Tyre, but which in fact was so laced with allusions to the Israelite high priest that the real thrust of the dirge could not possibly be missed by Ezekiel’s audience” (Robert Wilson, “The Death of the King of Tyre: The Editorial History of Ezekiel 28,” in Love and Death in the Ancient Near East: Essays in Honor of Marvin Pope, ed. John Marks and Robert Good [Guilford, CT: Four Quarters, 1987], 217). Ezekiel declares that because of his pride, greed, and corruption, the high priest in Jerusalem will be expelled from the Temple and destroyed.

I propose that Ezekiel’s priestly editors, unhappy with his condemnation of the high priest, have redirected his lament, adding a new heading identifying its referent as the king of Tyre (not mentioned after Ezek 28:12). Contrary to the NRSVue of Ezekiel 28:11-19, this passage is not about the fall of a cherub from heaven. Nor, however, is it about the first Human, or even the king of Tyre! It is a judgment oracle against Jerusalem’s high priest. However, it also serves to clarify both the identification of Eden with Zion, and the iconic function of the Temple cherubim.