Hebrew has no capital letters–which makes recognizing names a bit of a problem. As a beginning Hebrew student, I still remember doing what many of my own beginning students did later–failing to recognize that a name was a name, and laboriously trying to translate it. In my case it was David’s home town, “Bethlehem,” which I dutifully rendered as “house of bread”–until I pronounced the Hebrew aloud and realized what I was seeing.

The proper name “Adam” is of course used for the first man. However, in Gen 2:7, we find not a name, but the word ha‘adam (that is, “the human”), translated “human” in the CEB, but “man” in the NRSV. In the Hebrew text, ‘adam is not explicitly a name (presented without the article ha [“the”]) until Gen 4:25: “Adam knew his wife intimately again, and she gave birth to a son. She named him Seth.” However, in the Aramaic Targum, Adam is a name from Gen 2:7 on, while in the Greek Septuagint and the Vulgate, Adam is a proper name beginning with Gen 2:19, as the KJV reflects. So, what is the significance of this variation? Just when does ha’adam become Adam?

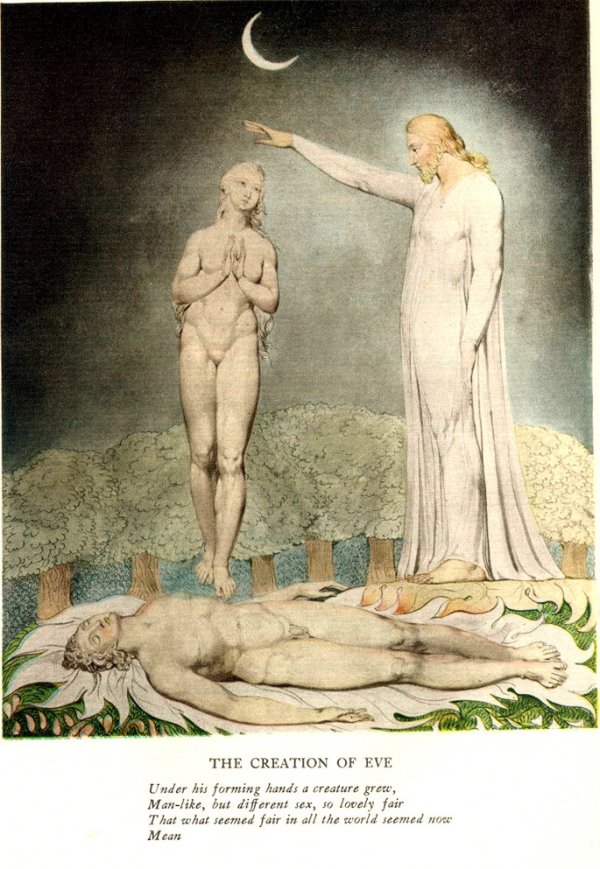

The creation of the Human is the first explicitly described creative act of God in this second creation account. Having first moistened the ground, “the Lord God formed man from the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and the man became a living being” (Gen 2:7 NRSVue).

There are several key terms to unpack in this verse. The verb translated “formed” in the NRSV is the Hebrew yatsar, the term for what potters do (for example, Isa 64:8 [7]; Jer 18:11). The Lord God is working in the wet soil, fashioning the human the way a potter fashions a pot on the wheel, or a sculptor fashions a statue from a bit of clay. In this story we are formed, intimately and intricately fashioned by the Lord God’s own fingers. However, the Lord God fashions ha’adam, the Human, not from potter’s clay, but from “the dust of the ground” (aphar min-ha’adamah).

“Dust” (Hebrew ‘aphar) suggests a dryness and sterility in curious contrast to the description of the now-moistened ground. In the Hebrew Bible, the word ‘aphar can connote human fragility and mortality (for example, Pss 119:25; 7:5; Dan 12:2), particularly in the phrase ‘aphar we’epher, “dust and ashes” (Gen 18:27; Job 30:19; 42:6). Likely, that usage derives from Gen 3:19:

By the sweat of your face

you shall eat bread

until you return to the ground,

for out of it you were taken;

you are dust,

and to dust you shall return (NRSVue).

But in Gen 2:7, the dust is specifically “the dust of the ground” (aphar min-ha’adamah), or better “the soil;” the Hebrew word ‘adamah is used in particular for arable land. Here, then, ‘aphar would appear to refer to the loose dirt at the surface of the ground that is plowed and planted—that is, the topsoil (see the CEB of this verse: “the LORD God formed the human from the topsoil of the fertile land”). It is this rich dirt, moistened with the water from beneath the earth, that is molded into ha’adam, the first human.

The Hebrew text deliberately puns on the words ‘adamah and ‘adam. Adam, we might say, is the mud man, fashioned from the soil. To capture that pun in English, we may think of ha’adam as the human made from the humus, or the earthling made from the earth.

The Human lives in the beautiful garden of Eden, with access to all the fruit ha’adam can eat, surrounded by beauty, and with fulfilling work to fill the Human’s days. Yet, there is something missing, and God Godself recognizes the problem: “Then the LORD God said, “It’s not good that the human is alone. I will make him a helper that is perfect for him” (Gen 2:18).

The Hebrew phrase rendered “helper that is perfect for him” is ‘ezer kenegedo. The word ‘ezer simply means “helper,’ which could perhaps be understood to mean something like “assistant.” But in the Hebrew Bible, ‘ezer is most commonly used for God (half of its citations: see Exod 18:4; Deut 33:7, 29; Pss 20:2[3]; 70:5[6]; 121:1-2; 124:8; 146:5), so subordination is unlikely to be the point. The fascinating expression kenegedo means “corresponding to him; in relationship to him.”

The KJV famously renders ‘ezer kenegedo as “an help meet”—that is, fitting, or appropriate—“for him,” which unfortunately spawned the term “helpmeet,” or “helpmate,” for a housewife duly submissive to her husband. The NRSV rendering “a helper as his partner” appropriately recognizes that the LORD God does not aim to find a subordinate, someone less than or under ha’adam. The Human is alone, and the quest is to find a being corresponding to ha’adam, with whom the Human can be in relationship.

The LORD realizes that a being truly corresponding to ha’adam must be fashioned from ha’adam’s very being; out of ha’adam’s own stuff:

The LORD realizes that a being truly corresponding to ha’adam must be fashioned from ha’adam’s very being; out of ha’adam’s own stuff:

So the Lord God caused a deep sleep to fall upon the man [ha’adam], and he slept; then he took one of his ribs [‘akhad mitsal’ohaw] and closed up its place with flesh. And the rib [tsela’] that the Lord God had taken from the man [ha’adam] he made into a woman [‘ishah] and brought her to the man [ha’adam] (Gen 2:21-22 NRSVue).

While most translations render the word tsela’ as “rib,” in the Hebrew Bible this word always means “side” (for example, the side of the Ark in Exod 25:12; the side of the Tabernacle in Exod 26:20; a hillside in 2 Sam 16:13; one of two double doors in 1 Kgs 6:34). Accordingly, in Bereshit Rabbah 8.1, R. Samuel bar Nahman says, “When the Holy One, blessed be he, created the first man, he created him with two faces, then sawed him into two [!] and made a back on one side and a back on the other.” When some objected that God had taken only a rib from ha’adam, “He said to them, ‘It was one of his sides, as you find written in Scripture, ‘And for the second side [tsela’] of the tabernacle’ (Ex. 26:20)’” (translated by Jacob Neusner). Rather than the Woman being made from a relatively insignificant portion of the Man, as is often held, Gen 2:20-21 describes major surgery: the Lord God uses one entire side of the original Human to fashion an ‘ezer kenegedo, basically splitting ha’adam in two!

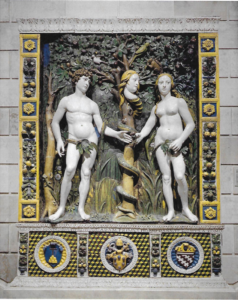

That mutuality is the point of this narrative is underlined by what ha’adam says upon meeting the Woman:

“This one finally is bone from my bones

and flesh from my flesh.

She will be called a woman

because from a man she was taken” (Gen 2:23).

Here at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh! At last I have somebody to talk to. At last I have someone who is like me and yet unlike me, with whom I can be in a relationship of equals.

In the PBS series Genesis: A Living Conversation, scholar and preacher Renita Weems says, “What do I think when I hear the phrase — ‘bone of my bone, and flesh of my flesh?’ This is the first love song a man ever sang to a woman.”

Here for the first time in this narrative (although most English translations obscure this), we find not ha’adam, the Human, but ‘ish, Man. Once more the Bible makes a point with a pun: just as ‘adam was taken from the ‘adamah, so ‘ishah has been taken from ‘ish. We should note that there is actually no etymological relationship between the words ‘ishah and ‘ish; they come from different roots in Hebrew. But just as the Human is inexorably bound up with the earth, so for this writer Man and Woman are inexorably bound up with one another.

The Greek and Latin versions, followed by the KJV, introduce the personal name Adam at the point in the narrative where the Woman’s origin story begins. The generic Human becomes a very specific person, with a name, once relationship with another created person comes into play. That’ll preach, friends.

Not only do Christians and Jews read and number the commandments differently, but different traditions within Christianity do as well. Roman Catholic and Lutheran churches, following the version of the Decalogue in Deuteronomy 5, appropriately regard coveting a neighbor’s wife and coveting a neighbor’s property as two different commandments: the ninth and the tenth, respectively. They avoid having eleven commandments by, with Jewish tradition, reading the prohibition of idols (

Not only do Christians and Jews read and number the commandments differently, but different traditions within Christianity do as well. Roman Catholic and Lutheran churches, following the version of the Decalogue in Deuteronomy 5, appropriately regard coveting a neighbor’s wife and coveting a neighbor’s property as two different commandments: the ninth and the tenth, respectively. They avoid having eleven commandments by, with Jewish tradition, reading the prohibition of idols (