The threefold battle cry of the Protestant Reformation was Sola gratia, sola fide, sola Scriptura: “Grace alone, faith alone, Scripture alone.” Against the claims of medieval Catholicism– that salvation came through the traditions of the Church, with its saints and sacraments and papal indulgences–Reformers such as Martin Luther asserted that we are saved by God’s grace alone, received through faith alone, and that all that is necessary for salvation is revealed through Scripture alone.

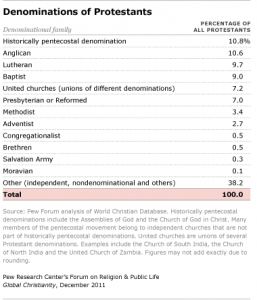

This emphasis on the primacy of Scripture rather than tradition has remained perhaps the central tenet of Protestantism. Yet curiously, adherence to “Scripture alone” has not unified the church. Rather, Protestant churches have continued to fission and fracture into a multitude of Christian expressions down to the present day, when nearly 40% of Protestant Christians worldwide identify as “independent, nondenominational or part of a denominational family that is very small or otherwise difficult to classify.”

The reason for this diversity, of course, is that the “one book” (or more accurately, the many books) of Scripture is interpreted in many different ways, by different Christians in their myriad contexts.

For example: John Wesley, leader of the Wesleyan revivals in eighteenth century England, famously referred to himself as homo unius libri, “a man of one book.”

I want to know one thing,—the way to heaven; how to land safe on that happy shore. God himself has condescended to teach me the way. For this very end He came from heaven. He hath written it down in a book. O give me that book! At any price, give me the book of God! I have it: here is knowledge enough for me. Let me be homo unius libri.

Yet, in the preface to his Sermons (where he identifies himself as homo unius libri), Wesley acknowledges that the meaning of Scripture is not always simple and straightforward:

Is there a doubt concerning the meaning of what I read? Does anything appear dark or intricate? I lift up my heart to the Father of Lights:—“Lord, is it not Thy word, ‘if any man lack wisdom, let him ask of God?’ Thou givest liberally, and upbraidest not. Thou hast said, ‘if any be willing to do Thy will, he shall know.’ I am willing to do, let me know Thy will.” I then search after and consider parallel passages of Scripture, “comparing spiritual things with spiritual.” I meditate thereon with all the attention and earnestness of which my mind is capable. If any doubt still remains, I consult those who are experienced in the things of God: and then the writings whereby, being dead, they yet speak. And what I thus learn, that I teach.

The interpretation of Scripture requires prayerful reflection and spiritual discernment–that is, a personal experience of devotion to God through Christ and of yieldedness to the Holy Spirit. Understanding the Bible requires study–that is, the exercise of reason!–and so the careful consultation of other books. Faithful interpretation of Scripture calls us to enter into conversation with other believers past and present: in short, with the tradition. All claims to the contrary, then, sola Scriptura strictly understood is an unobtainable–indeed, an undesirable–goal.

Often, Christians who insist upon the Bible’s absolute and infallible authority refer to 2 Timothy 3:16-17. In the CEB, this passage reads:

Every scripture is inspired by God and is useful for teaching, for showing mistakes, for correcting, and for training character, so that the person who belongs to God can be equipped to do everything that is good (compare KJV and NRSV of these verses).

The highlighted phrase is a single word in Greek: theopneustos. The NIV famously renders this as “All Scripture is God-breathed“–which is, literally, what theopneustos (combining the Greek words for “God” and “breath”) would seem to mean. This reading of theopneustos is followed in the ESV, and in Eugene Petersen’s popular paraphrase The Message. Christians who insist upon the Bible’s inerrancy–that is, its absolute and infallible authority–often cite this passage. Surely, if the Bible is God-breathed, that must mean that its words are God’s very words, as perfect and infallible as God is, and carrying God’s own authority.

This is the position of Josh McDowell, whose book God-Breathed sets out “to present a compelling case that God’s Word can be trusted to be undeniably reliable.” As McDowell states,

Each book, each page and each paragraph of Scripture was written through the lens of its human spokesmen, yet it still communicates the exact message God wants us to receive. . . . His words were supernaturally guided through his selected human instruments so that his truth would be vivid and relevant to our lives. With God as the author and men as the writers, the sixty-six books of the Bible can rightly be called the Word of God.

But the derivation of a word is not necessarily a reliable guide to its meaning. Consider that the “literal” meaning of the word “sarcophagus” is “flesh-eater”! A surer guide to what theopneustos means would be how the word is actually used elsewhere. Unfortunately, this word is uncommon: it appears nowhere else in the New Testament; nor is it used in the Greek translation of Jewish Scripture, the Septuagint.

Outside of the Bible, the term is no less obscure. In the Sentences of Pseudo-Phocylides, a first-century Jewish philosopher, theopneustos is used to distinguish wisdom from God from human wisdom (Sentences 129); note, though, as P. W. van der Horst observes, “This line, in clumsy [Greek], is probably inauthentic. It is lacking in some important textual witnesses” (The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, Vol. 2, ed. James H. Charlesworth [Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1985], 579). In a compendium of the teachings of the philosophers ascribed to the first-century historian Plutarch, but likely written much later than his time, theopneustos is used to distinguish “dreams which are caused by divine instinct” from “dreams which have their origin . . . from the soul’s forming within itself the images of those things which are convenient for it” (Placita Philosophorum 5. 2. 3). Perhaps characterizing the Bible as theopneustos sets it apart as sacred writing, different from other, ordinary books.

Another way into this question is to ask what we usually mean when we speak of inspiration (a word which is also related to breath). Methodist theologian William Abraham considers what it means when we say that a teacher is inspiring, or that a teacher’s students have been inspired:

. . . there is no question of students being passive while they are being inspired. On the contrary: their natural abilities will be used to the full extent, and as a result they will show great differences in style, content and vocabulary. Their native intelligence and talent will be greatly enhanced and enriched but in no way obliterated or passed over. . . . there need be no surprise if, from the point of view of the teacher, they make mistakes (William J. Abraham, The Divine Inspiration of Holy Scripture [Oxford: Oxford University, 1981], 63-64).

As a Bible teacher, this illustration resonates strongly with me. I do indeed hope that I inspire my students. But by that, I certainly do not mean that I expect them to repeat my own words by rote, or even that I expect them to think just as I do. I do hope that they will love the Bible as I do, and that through their study they will be led into a deeper and deeper relationship with the God of Scripture.

Applying this analogy of classroom inspiration to Scripture, Abraham writes:

We must allow a genuine freedom to God as he inspires his chosen witnesses, knowing that what he does will be adequate for his saving and sanctifying purposes for our lives. In so doing we escape the tension and artificiality of those theories that have staked everything on the perfectionist and utopian hopes that stem from a theology of Scripture that substitutes divine speaking [i.e., “the Bible is the literal word of God”] for divine inspiration without biblical or rational warrant (Abraham, Inspiration, 69-70).

While Abraham’s statement that the Bible is “adequate” to God’s saving purposes may seem to us far too weak, it is not much different than the claim that the writer of 2 Timothy makes. Scripture is “useful”–not infallible, not inerrant, not even authoritative, but “useful”:

for teaching, for showing mistakes, for correcting, and for training character, so that the person who belongs to God can be equipped to do everything that is good

As Daniel Migliore observes, “Scripture is indispensable in bringing us into a new relationship with the living God through Christ by the power of the Holy Spirit.” However, “Christians do not believe in the Bible; they believe in the living God attested by the Bible” (Daniel L. Migliore, Faith Seeking Understanding: An Introduction to Christian Theology, Second Edition [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004], 50).

The Bible is not an end–it is a means to an end. These ancient words express the faith of women and men who were enlivened and transformed by God’s presence; hearing their words, we are brought into an encounter with the same God, and equipped for service in God’s world.