We Methodists love to recall that on this day 281 years ago–May 24, 1738–John Wesley went “very unwillingly” to a prayer meeting at Aldersgate Street in London. There “about a quarter before 9, while one was reading from Luther’s preface to the Letter to the Romans, I felt my heart strangely warmed.” In that moment, Wesley wrote, he felt the assurance that Christ “had taken away my sins, even mine.” It is good, and right, that we celebrate this day.

But in 1766, 28 years after Aldersgate, Wesley wrote in a letter to his brother Charles,

“[I do not love God. I never did]. Therefore [I never] believed, in the Christian sense of the word. Therefore [I am only an] honest heathen, a proselyte of the Temple.”

The parts in brackets were written in the Wesleys’ private shorthand–as though, even in a private letter to his brother, John was deeply ashamed of this confession! But we need to remember this too, friends. Wesley’s Aldersgate certainty was not always before him. He continued, long after, to wrestle with his faith and with his God.

Later, in the very same letter in which he sorrowfully acknowledges, “[I never] believed, in the Christian sense of the word,” Wesley writes, “I find rather an increase than a decrease of zeal for the whole work of God and every part of it,” and urges his brother Charles, “O insist everywhere on full redemption, receivable by faith alone; consequently, to be looked for now.” The point, friends, is that faith and doubt lived together in John Wesley’s heart–in short, that he was one of us! Wesley certainly did not regard his own experience or ideas as changeless norms.

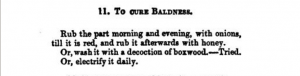

This is important, for a vital conversation in our movement right now concerns what it means to be “Wesleyan.” One understanding of that term is that to be Wesleyan is to think what Wesley thought: to regard his sermons and commentaries and other writings as the compendium of what we too are to think and believe. Most, of course, will recognize that not all of Wesley’s words are equal: few, for example, will think that we should embrace his medical advice:

However, we may think that Wesley’s biblical interpretations ought to be embraced by anyone who calls herself a Wesleyan: so, a Wesleyan reading of Scripture would be one that agrees with Wesley’s positions in his sermons and commentaries.

Certainly, John Wesley greatly valued the Scriptures:

Indeed, Wesley famously referred to himself as homo unius libri, or “a man of one book”–that is, the Bible:

I want to know one thing,—the way to heaven; how to land safe on that happy shore. God himself has condescended to teach me the way. For this very end He came from heaven. He hath written it down in a book. O give me that book! At any price, give me the book of God! I have it: here is knowledge enough for me. Let me be homo unius libri.

However, in the preface to his Sermons (where he identifies himself as homo unius libri), Wesley also acknowledges that the meaning of Scripture is not always simple and straightforward:

Is there a doubt concerning the meaning of what I read? Does anything appear dark or intricate? I lift up my heart to the Father of Lights:—“Lord, is it not Thy word, ‘if any man lack wisdom, let him ask of God?’ Thou givest liberally, and upbraidest not. Thou hast said, ‘if any be willing to do Thy will, he shall know.’ I am willing to do, let me know Thy will.” I then search after and consider parallel passages of Scripture, “comparing spiritual things with spiritual.” I meditate thereon with all the attention and earnestness of which my mind is capable. If any doubt still remains, I consult those who are experienced in the things of God: and then the writings whereby, being dead, they yet speak. And what I thus learn, that I teach.

Friends, I propose that here in this preface Wesley lays out a Wesleyan method for the interpretation of Scripture: a way to read the Bible with Wesley, reading as he read, if not necessarily drawing the same conclusions he did. It is an approach to the Bible that recognizes the depth of Scripture: not only that the meaning of a passage may not be immediately apparent, but also that the meaning of Scripture is not exhausted by any single interpretation.

Not surprisingly, Wesley’s method reflects what Methodist scholar Albert Outler famously called the Wesleyan Quadrilateral. Scripture itself comes first in that tally, of course. But a Wesleyan reading of Scripture requires prayerful reflection and spiritual discernment–that is, a personal experience of devotion to God through Christ and of yieldedness to the Holy Spirit. Indeed, the Bible is not itself an end, in this Wesleyan reading, but a means to an end–that is, an encounter with the living God of Scripture through Jesus Christ.

This approach to Scripture was upheld by another British Christian, long after Wesley: the famous Christian writer and thinker C.S. Lewis. In a letter to a Mrs. Johnson, on November 8th, 1952, Lewis wrote:

It is Christ Himself, not the Bible, who is the true Word of God. The Bible, read in the right spirit and with the guidance of good teachers will bring us to Him. When it becomes really necessary (i.e. for our spiritual life, not for controversy or curiosity) to know whether a particular passage is rightly translated or is Myth (but of course Myth specially chosen by God from among countless Myths to carry a spiritual truth) or history, we shall no doubt be guided to the right answer. But we must not use the Bible (our ancestors too often did) as a sort of Encyclopedia out of which texts (isolated from their context and read without attention to the whole nature and purport of the books in which they occur) can be taken for use as weapons.

If the Bible is indeed a means rather than an end, then reading and applying Scripture must mean more than looking up “what the Bible says” about any particular issue–let alone what Wesley says!–and then stating that as our position. Understanding the Bible also requires study–that is, the exercise of reason! As John Wesley wrote, “I meditate thereon with all the attention and earnestness of which my mind is capable.”

Bible study means immersion in the Scriptures–searching out, as Wesley says, “parallel passages of Scripture, ‘comparing spiritual things with spiritual.'[1 Cor 2:13]” We need to read the Bible in big hunks, always attentive to the way that Scripture continually alludes to itself. Here, the UM Publishing House’s excellent resource, the Disciple Bible Study series, is a great help. Serious Bible study will also require the careful consultation of other books: commentaries, Bible dictionaries, the best of current scholarship.

Wesley writes, “If any doubt still remains, I consult those who are experienced in the things of God: and then the writings whereby, being dead, they yet speak.” Faithful interpretation of Scripture calls us to enter into conversation with other believers, past and present: in short, with the tradition. But it is clear from the method laid out here, as well as from Wesley’s entire ministry, that he did not regard slavish adherence to tradition as a goal.

The end of Bible study, for Wesley, is application through teaching and preaching: “And what I thus learn, that I teach.” But Wesley also remained aware of the need for openness to others. In his Sermon 39, on the “Catholic Spirit,” John Wesley unpacked 2 Kings 10:15:

And when [Jehu] was departed thence, he lighted on Jehonadab the son of Rechab coming to meet him: and he saluted him, and said to him, ‘Is thine heart right, as my heart is with thy heart?’ And Jehonadab answered, ‘It is.’ ‘If it be, give me thine hand.’ And he gave him his hand; and he took him up to him into the chariot [KJV].

Wesley declared this as his own view with regard to sisters and brothers who were not Methodist: “Is thine heart right, as my heart is with thy heart? If it be, give me thine hand.”

I do not mean, “Be of my opinion.” You need not: I do not expect or desire it. Neither do I mean, “I will be of your opinion.” I cannot, it does not depend on my choice: I can no more think, than I can see or hear, as I will. Keep you your opinion; I mine; and that as steadily as ever. You need not even endeavour to come over to me, or bring me over to you. I do not desire you to dispute those points, or to hear or speak one word concerning them. Let all opinions alone on one side and the other: only “give me thine hand.”

Wesley argued that every Christian must hold her or his convictions firmly:

A man of a truly catholic spirit has not now his religion to seek… he is always ready to hear and weigh whatsoever can be offered against his principles; but as this does not show any wavering in his own mind, so neither does it occasion any.

That said, however, Wesley was also fully aware that “humanum est errare et nescire: ‘To be ignorant of many things, and to mistake in some, is the necessary condition of humanity’” (Wesley’s own translation of an inscription on the tomb of John Sheffield, Duke of Buckingham, in Westminster Abbey)—that is, “He knows, in the general, that he himself is mistaken; although in what particulars he mistakes, he does not, perhaps he cannot, know.” This realization necessitates, in any reasonable person, a generosity of spirit:

Every wise man, therefore, will allow others the same liberty of thinking which he desires they should allow him; and will no more insist on their embracing his opinions, than he would have them to insist on his embracing theirs. He bears with those who differ from him, and only asks him with whom he desires to unite in love that single question, “Is thy heart right, as my heart is with thy heart”?

It is my prayer that the people called Methodists in our own day may learn that same generosity of spirit, as we wrestle together with God’s Word in Scripture.