The Hebrew Bible text for Sunday in the Revised Common Lectionary is Amos 7:7-17, which begins with a vision report:

This is what the Lord showed me: The Lord was standing by a wall, with a plumb line in his hand. The Lord said to me, “Amos, what do you see?”

“A plumb line,” I said.

Then the Lord said,

“See, I am setting a plumb line

in the middle of my people Israel.

I will never again forgive them.

The shrines of Isaac will be made desolate,

and the holy places of Israel will be laid waste,

and I will rise against the house of Jeroboam with the sword” (Amos 7:7-9).

This famous prophetic image is beautifully reflected in a prayer for the day from the Lectionary’s editors:

Steadfast God, your prophets set the plumb line

of your righteousness and truth

in the midst of your people.

Grant us the courage to judge ourselves against it.

Straighten all that is crooked or warped within us

until our hearts and souls stretch upright,

blameless and holy,

to meet the glory of Christ. Amen.

The trouble is, this translation of our passage is suspect. The word rendered “plumb line” in the Common English Bible is ‘anak, which actually means “tin.” In Amos’ vision, the LORD is standing al-khomath ‘anak (“beside a wall of tin”), holding ‘anak (“a piece of tin”) in God’s hand.

The ancient versions attempt in various ways to come to terms with this Hebrew original. The Greek Septuagint reads teichous adamantinou (an impenetrable, that is metal-sheathed, wall), and in the LORD’s hand is a piece of metal (adamas). The Latin Vulgate, understanding the piece of metal in God’s hand to be a trowel (trullu cementarii), has the LORD standing on a plastered wall (murum litum). The Aramaic Targum, as it generally does, eschews metaphor for what its translators thought the metaphor actually intended–here, the wall is a place of judgment (Aramaic din), and a judgment against Israel is in the LORD’s hand.

The reading “plumb line” is relatively recent, going back only to the medieval Jewish interpreter Ibn Ezra (1089-1164). However, it was popularized by Martin Luther in his 1534 translation of the Bible into German (which uses the German Bleischnur, meaning “plumb line,” here) and today is found in nearly every English translation (see some examples here). Even the Jewish Publication Society’s Tanak (an abbreviation for Torah [Law], Nebi’im [Prophets], and Kethubim [Writings], the three parts of the Hebrew Bible) has “plumb line,” although footnotes in the NJPS translation suggest that the LORD holds a pickaxe, and that the wall is “destined for a pickaxe”! In the end, the footnotes say, the meaning of the Hebrew is uncertain.

However, as we have seen, the Hebrew is not at all uncertain: in Amos’ vision, the LORD stands by a wall of tin–or perhaps, a wall sheathed in tin–holding a piece of tin. God says that God is placing tin “in the middle of my people Israel; I will never again forgive them” (7:8). What the text says is plain. The question is, what does this mean?

Both Ibn Ezra and Luther apparently understood the metal in this vision to be the weight on a plumb line, and the wall to have been built using a plumb line. The point of the vision therefore is that God is holding Israel to account, testing that they are true to the LORD as a mason uses a plumb to test whether a wall is truly vertical. However, plumb bobs were made of stone or lead, not tin (note that the German Bleischnur used by Luther literally means “lead line”). The ancient versions all seem, similarly, to interpret based on the metal. But comparison with Amos’ other visions suggests another possibility.

In Amos 8:1-2, the prophet is shown a basket of summer fruit (Hebrew qayits) and told, “The end [qets] has come upon my people Israel; I will never again forgive them” (compare 7:8, where that same expression is found). His vision is not about qayits (“summer fruit”) at all, but about the word “qayits”—a punning reference to Israel’s end (qets). So too, Jeremiah sees the branch of an almond tree (Hebrew shaqed), and is told, “I am watching [shoqed] over my word to perform it” (Jer 1:11-12). So what if Amos 7:7-9 is also a pun? What if the point of Amos’ vision is not ‘anak (“tin”), but something that sounds like ‘anak?

As S. Dean McBride, Jr. notes, the second person singular pronoun (“you”) in Hebrew has a complex history. The free-standing form of the pronoun is ‘atta (contracted from an original ‘anta) or ‘at; however, the pronoun may be appended to a noun as ka or ak (meaning “your”). The first-person pronoun may offer a clue to this complexity. While later Hebrew texts prefer the shortened form ‘ani, the older form ‘anoki is also common. Some Semiticists propose that the older form of the second person pronoun may have similarly been something like ‘anak. McBride proposes that Amos’ vision of ‘anak, “tin,” in 7:7-9 is a pun on an archaic ‘anak[?], “you” (like qayits/qets in 8:1).

If this is so, then God is telling Amos, “I am placing YOU in the middle of my people Israel” (7:8)–making this vision Amos’ call to prophesy.

The narrative in Amos 7:10-17 shows us Amos snatched from his home in the village of Tekoa, in the southern kingdom of Judah, and placed by God in Bethel, one of the great cities of the northern kingdom of Israel. There, Amos’ message of justice places him in opposition to both the high priest Amaziah and the northern political leader, Jeroboam II–which is not comfortable for the high priest or the king. However, it is not comfortable for Amos, either! He protests to Amaziah (and to us!) that this life was not his choice:

I am not a prophet, nor am I a prophet’s son; but I am a shepherd, and a trimmer of sycamore trees. But the Lord took me from shepherding the flock, and the Lord said to me, ‘Go, prophesy to my people Israel.’ (Amos 7:14-15)

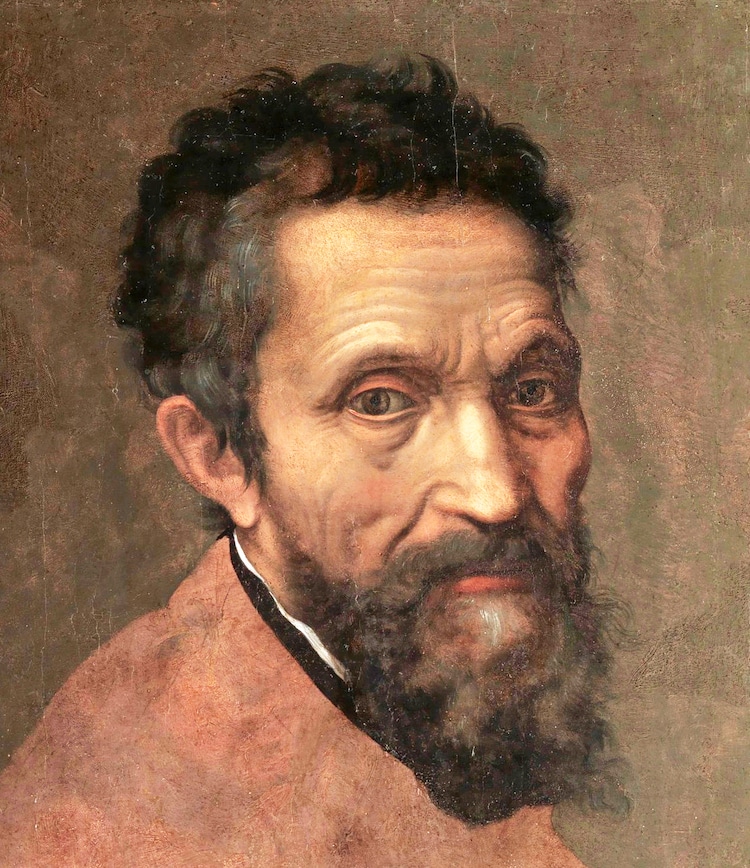

I am reminded of Michelangelo, who always regarded himself as a sculptor rather than a painter. So, throughout the years he spent painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling at the Pope’s command, Michelangelo stubbornly signed his letters “Michelangelo, Sculptor.”

Similarly, Amos saw himself as a shepherd, not a prophet. Had he had his own way, he would never have left home! But there is no doubt in Amos’ mind that he is in the right place, whether it is the place he would have chosen or not. He is where he is because God has put him there: “the LORD took me from shepherding the flock” (7:15). Amos was not comfortable. Nor strictly speaking, was he successful: his passionate summons to God’s way of justice (Amos 5:21-24) went unheeded, and as he had warned, the northern kingdom fell to the Assyrians. But Amos was faithful–and that is what mattered.

Just as God spoke to Amos, so God says to us, in our day, “I am placing you in the midst of my people.” If we believed that following Christ’s call would save us from conflict and discomfort, we were laboring under a major misapprehension! It is not hard to see how we could have gotten there: knowing that God is love, we concluded thereby that God is nice, and wants us to have a nice life: peaceful and conflict-free. But it was not so for Amos, or for John, or for Jesus, and it will not be so for us! God is love–but love wills the good, not the nice; justice, not expedience. Elsewhere in his prophecy, Amos makes this plain: “Woe to them that are at ease in Zion!” (Amos 6:1, KJV).

We too, I am persuaded, have been placed in the midst of God’s people in our day, and so in the midst of conflict and controversy. God has called and empowered us, friends, for just such a time as this. As Charles Wesley’s powerful hymn reminds us,

To serve the present age,

My calling to fulfill:

Oh, may it all my pow’rs engage

To do my Master’s will!

Wesley is starkly–indeed, terrifyingly!–forthright regarding the stakes of our faithfulness to that call:

Help me to watch and pray,

And on Thyself rely,

Assured, if I my trust betray,

I shall forever die.

God grant that we, like Amos, will be faithful to our call.

Fascinating. And, at least in my mind, it fits well with the Good Samaritan story from Luke also in the RCL. I may have to do some revising before Sunday…