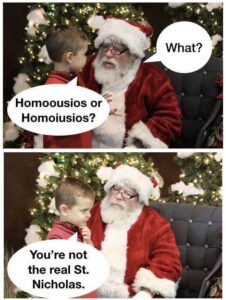

Every year (despite the unfortunate typo: that should be homoiousias), I repost this chestnut from “Orthodox Christian Memes.” And every year, someone doesn’t get it. So, on this the feast day of St. Nicholas of Myra (in the Western Church; in Eastern Churches, it is December 19), what’s the joke–and why does it matter?

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, St. Nicholas was

Bishop of Myra in Lycia; died 6 December, 345 or 352. Though he is one of the most popular saints in the Greek as well as the Latin Church, there is scarcely anything historically certain about him except that he was Bishop of Myra in the fourth century.

Some of the main points in his legend are as follows: He was born at Parara, a city of Lycia in Asia Minor; in his youth he made a pilgrimage to Egypt and Palestine; shortly after his return he became Bishop of Myra; cast into prison during the persecution of Diocletian [284 to 305 CE], he was released after the accession of Constantine [306 to 337 CE], and was present at the Council of Nicaea.

Legend also connects St. Nicholas to gift-giving at Christmas, and specifically to hanging stockings–hence, the association of Christmas and St. Nicholas, aka Santa Claus. But, what about the meme with which we began?

Part of St. Nicholas’ legend is that, at the Council of Nicaea, he punched out Arius for denying the full divinity of Christ! At issue were the Greek terms homoiousias and homoousias. According to Arius and his followers, Jesus was a creation of God–the highest creature to be sure, indeed the first-born of all creation, but still distinct from the one God. Jesus and God are therefore homoiousias: of like substance, or essence. To be fair, this kind of language is used in Scripture. Colossians 1:15 describes Jesus as “the image of the invisible God, the one who is first [Greek prototokos, “firstborn“] over all creation.” The Christ hymn in Philippians 2:6-11 says that

Though he was in the form of God,

he did not consider being equal with God something to exploit.

But he emptied himself

by taking the form of a slave

and by becoming like human beings (Phil 2:6-7).

The Council, however, wound up affirming–with Nicholas, and against Arius–that Jesus and God were homoousias: that is, of the same substance, or of one substance. The Nicene Creed accordingly confesses,

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ,

the only Son of God,

eternally begotten of the Father,

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made,

of one Being [Greek homoousion] with the Father.

Through him all things were made.

As old friend, ministry colleague, and shameless punster Frank Norris observes, there is way more than an iota of difference between homoousias and homoiousias! Jesus and God are one!

So, why did the Council at Nicaea make this confession? Theologian George Lindbeck has argued that Trinitarian theology grows out of the struggle of early Christians to speak plainly about their experience of God. Early on, the first Christians needed to affirm, on the one hand, the continuity of their faith with the faith of ancient Israel: the God they loved and worshipped was Abraham’s God. But at the same time, they needed to speak of Jesus in the most exalted language possible (what Lindbeck terms “Christological maximalism”), as they had come to know God, intimately and personally, through him. Hence, the New Testament calls Jesus God’s Son (The Nature of Doctrine [Nashville: Westminster John Knox, 1984], 94).

As St. Nicholas insisted, and as the Council at Nicaea affirmed, it is true that Jesus is divine; yet it is also true that God is one. That may seem nonsensical–but the Trinity is not a logic problem for us to solve! We come to the paradoxical language of Trinity because we are driven to it by the shape of our experience of God. The doctrine of the Trinity emerges out of our struggle to talk meaningfully about who God is, and what God is up to in our world.

Full-blown Trinitarian language is wanting in the texts of Scripture, but the Gospel of John comes very close. John 1:1 affirms,

In the beginning was the Word

and the Word was with God

and the Word was God.

Indeed, in John 10:30, Jesus proclaims, “I and the Father are one.” In John 16:14-15, Jesus speaks of the Spirit who “will take what is mine and proclaim it to you” (16:14), yet also says “Everything that the Father has is mine” (16:15). Jesus, the Spirit, and the Father are distinct, yet intimately related.

1 John 4:8 gives us another way to visualize the Divine life: “God is love.” The greatest power in the universe is self-giving, sacrificial love! God in Godself is at once the Lover, and the Beloved, and the Love that binds them as one. God in Godself is relationship, and community!

The early Christians were not the first to realize this. The sages of ancient Israel looked for a way of talking about God as, on the one hand, separate from the world and its objects, and on the other, as intimately involved and engaged with the world. Particularly in Proverbs 8, they described divine Wisdom itself as a person: a woman, as the Hebrew word for Wisdom (khokmah) is feminine.

Lady Wisdom says, “The LORD created me [Hebrew qanani; perhaps better “acquired me,” that is, as a wife] at the beginning of his way, before his deeds long in the past” (Proverbs 8:22). Through Wisdom, God creates a world reflecting God’s own character and identity: a community, a web of interrelationships, every part working together and responding to every other part, on every level.

I was formed in ancient times,

at the beginning, before the earth was.

When there were no watery depths, I was brought forth,

when there were no springs flowing with water.

Before the mountains were settled,

before the hills, I was brought forth;

before God made the earth and the fields

or the first of the dry land.

I was there when he established the heavens,

when he marked out the horizon on the deep sea,

when he thickened the clouds above,

when he secured the fountains of the deep,

when he set a limit for the sea,

so the water couldn’t go beyond his command,

when he marked out the earth’s foundations.

I was beside him as a master of crafts.

I was having fun,

smiling before him all the time,

frolicking with his inhabited earth

and delighting in the human race (Prov 8:23-31).

Christian readers will be reminded, again, of John 1:1-3:

In the beginning was the Word

and the Word was with God

and the Word was God.

The Word was with God in the beginning.

Everything came into being through the Word,

and without the Word

nothing came into being.

Here, Christ is the Word of God who is God, through whom the world was made. This is a Wisdom Christology: a way of talking about Christ drawn from the language of Proverbs 8!

The first chapter of John goes on to give us John’s version of the Christmas story:

The true light that shines on all people

was coming into the world.

The light was in the world,

and the world came into being through the light,

but the world didn’t recognize the light.

The light came to his own people,

and his own people didn’t welcome him.

But those who did welcome him,

those who believed in his name,

he authorized to become God’s children,

born not from blood

nor from human desire or passion,

but born from God.

The Word became flesh

and made his home among us.

We have seen his glory,

glory like that of a father’s only son,

full of grace and truth (John 1:9-14).

It is, granted, an unusual Christmas story—without a shepherd, wise man, or manger in sight! That is because, rather than telling a story about Christ’s birth, John considers the meaning of his birth: the mystery of the Incarnation.

Both Matthew and Luke begin their gospels by setting Jesus’ life and ministry in history: he was born in Palestine, in Bethlehem, in the reigns of Caesar Augustus and Herod. But John’s gospel opens in eternity: En arche he logos—“In the beginning was the Word” (John 1:1). Any reader of Scripture will think immediately of the very first chapter of Scripture, where God speaks the universe into being, creating by means of God’s word: “Then God said, ‘Let there be light;’ and there was light” (Gen 1:3; cf. 1:6, 9,11,14, 20, 24). But for John’s Greek-speaking audience, there would have been another resonance to this language. Logos of course means “word,” but Greek Stoic philosophers also used Logos as their name for the ordering principle behind all reality.

Astonishingly, John 1:14 asserts “And the Word became flesh and lived among us.” In Greek, “flesh” is sarx: a satisfactorily ugly word for the stuff of which people are made. The logos, God’s creative Word, the very structure of the universe, has become sarx. That is, quite literally, what “incarnation” means. To understand the Latin root of the word, you don’t need to know Latin—you just need to be a fan of Mexican food. “Chili con carne” is, of course, chili with meat. The incarnation is the “in-meat-ment” of the Divine!

What a bizarre thing to say! In fact, we Christians are the only ones who make such a claim about God. Many find it inconceivable, if not offensive, to imagine the unimaginable God in such a way—eternity somehow collapsed into time, omnipresence folded into such a small and scandalously specific place as a baby, in a manger, in Bethlehem. And they are right—it is offensive, inconceivable, a paradox, a mystery—but it is also the claim at the center of our Christian faith.

St. Nicholas was right, friends. Jesus IS God. In him, God has shown us a human face, has spoken to us with a human voice, has touched us with human hands. In the person of Jesus, God has come to us as one of us.