March 17 is the feast of Saint Pádraig–better known as Patrick, patron saint of Ireland. The saint was likely born in the late fourth century; according to Saint Fiacc’s “Hymn of Saint Patrick,” he was the son of a Briton named Calpurnius. Patrick was just sixteen when he was kidnapped from the family estate, along with many others, by Irish raiders. He would be a slave in Ireland for six years.

Once he was free, Patrick studied for the priesthood under Saint Germanus of Auxerre, in the southern part of Gaul. Saint Germanus took his pupil to Britain to save that country from Pelagianism: together they travelled through Britain convincing people to turn to God from heresy, and throwing out false priests (some say that this is the source of the legend that Patrick drove the “snakes” out of Ireland!).

Despite his experience of hardship and abuse as a slave, Patrick longed to return to Ireland. He told his teacher that he had often heard the voice of the Irish children calling to him, “Come, Holy Patrick, and make us saved.” But Patrick had to wait until he was sixty years old before Pope Celestine at last consecrated him as Bishop to Ireland. At the moment of Patrick’s consecration, legend says, the Pope also heard the voices of the Irish children!

That year, Easter coincided with the “feast of Tara,” or Beltane–still celebrated today by kindling bonfires. No fire was supposed to be lit that night until the Druid’s fire had been kindled. But Saint Patrick lit the Easter fire first. Laoghaire, high king of Ireland, warned that if that fire were not stamped out, it would never afterward be extinguished in Erin.

King Laoghaire invited the Bishop and his companions to his castle at Tara the next day–after posting soldiers along the road, to assassinate them! But, according to The Tripartite Life, on his way from Slane to Tara that Easter Sunday, Patrick was reciting his Breastplate prayer (a masterpiece of Celtic spirituality, which has, not at all surprisingly, been set to music many, many times; the links in this blog will take you to a few of these). As the saint prayed,

A cloak of darkness went over them so that not a man of them appeared. Howbeit, the enemy who were waiting to ambush them, saw eight deer going past them…. That was Saint Patrick with his eight…

Therefore, “St. Patrick’s Breastplate” is also called the “Deer’s Cry.”

As the legend of the Deer’s Cry demonstrates, Celtic spirituality is linked closely to nature. St. Patrick’s teaching embraced God’s presence manifest in God’s creation. Even the tradition that Patrick used the shamrock to teach the Trinity connects God’s revelation to the natural world. This is particularly evident, however, in the Breastplate prayer:

I arise today

Through the strength of heaven:

Light of sun,

Radiance of moon,

Splendor of fire,

Speed of lightning,

Swiftness of wind,

Depth of sea,

Stability of earth,

Firmness of rock.

In the Book of the Twelve, God’s presence manifest through the natural world is presumed in the book of Haggai. Haggai’s prophecy began “in the second year of King Darius, in the sixth month on the first day of the month” (Hag 1:1)–that is, August 29, 520 BC, about seventeen years after the fall of Babylon, and the end of the Babylonian exile. Together with his fellow prophet Zechariah, Haggai called for the community in Jerusalem to rebuild the temple, which had been in ruins since the Babylonians destroyed the city in 587 BC.

Haggai 1:3-11 joins fertility and abundance to God’s presence, enshrined and celebrated in the right temple with the right liturgy. Patrick celebrates this theme positively, through a joyful nature spirituality wherein a simple herb expresses the mystery of God’s nature, the vibrancy and constancy of wind and water and stone and tree witness to God’s presence and power, and the line between the human world and the animal world, between people and deer, can blur and vanish.

But in Haggai, this theme is expressed negatively. The failure of the community to rebuild God’s temple has meant disaster–not only for the human community, but also for the land itself. Just as for Patrick the presence of God, honored and celebrated in true worship, brings life and blessing to the land, for Haggai the absence of God’s temple has brought death, infertility, and drought:

Therefore, the skies above you have withheld the dew,

and the earth has withheld its produce because of you.

I have called for drought on the earth,

on the mountains, on the grain,

on the wine, on the olive oil,

on that which comes forth from the fertile ground,

on humanity, on beasts,

and upon everything that handles produce (Hag 1:10-11).

Haggai challenges his community,

Is it time for you to dwell in your own paneled houses

while this house lies in ruins?

So now, this is what the Lord of heavenly forces says:

Take your ways to heart.

You have sown much, but it has brought little.

You eat, but there’s not enough to satisfy.

You drink, but not enough to get drunk.

There is clothing, but not enough to keep warm.

Anyone earning wages puts those wages into a bag with holes (Hag 1:4-6).

As Stephen Cook observes, Haggai makes a clear connection between the temple lying “in ruins” (1:4; Hebrew khareb) and the “drought [Hebrew khoreb] on the earth” (1:11; see Stephen Cook, “Haggai,” “Zechariah,” and “Malachi” in The New Interpreter’s Bible One-Volume Commentary [ed. Beverly Roberts Gaventa and David Petersen; Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 2010], 529–539.).

For Haggai, since God’s presence in the temple was the source of life and fertility in all the land, the refusal of the people to rebuild the temple had resulted in God’s absence, and so in infertility and drought. In the great baseball film “Field of Dreams,” a Voice prompts Ray Kinsella to carve a baseball field out of his Iowa cornfields, saying, “If you build it, he will come.” Just so, Haggai urges his community to action:

Go up to the highlands and bring back wood.

Rebuild the temple so that I may enjoy it

and that I may be honored, says the LORD (Hag 1:8).

“If you build it,” Haggai assures his people, “he will come.”

We may see connections between Haggai’s temple theology and the modern “prosperity gospel,” which promises health, wealth, and success to those who believe the right things, and pray in the right way. But this so-called “gospel” is actually an outrageous misappropriation of Haggai’s theology. Haggai does not tell his community what they must do in order to prosper. Indeed, he lays the blame for their currently unfulfilled lives on their pursuit of prosperity. Haggai 1:4 asks, “Is it time for you to dwell in your own paneled houses while this house lies in ruins?” The reference to paneling (Hebrew saphun) calls to mind the opulence of the royal palaces of Solomon (1 Kings 7:7) and Jehoiakim (Jeremiah 22:14). Haggai’s community, with their “paneled houses,” had aspired to that former wealth and prosperity, and in so doing had placed themselves first, and God last.

But this way of living had not brought them the satisfaction and fulfillment they sought; in fact, it had desolated both them and their land. Only by obeying God’s command through the prophet to rebuild the temple, and so placing God first, could Haggai’s community not only find the fulfillment that had eluded them, but also heal their land.

This St. Patrick’s Day, may we listen to the message of the saint–a message proclaimed long before him by prophets like Haggai. May we seek God first, and so find fulfillment for ourselves and for God’s world.

Oh, and–Erin go bragh!

AFTERWORD

Here is the complete traditional text of the “Breastplate of St. Patrick.” Beannachtai Na Feile Padraig Oraibh–May the blessing of St. Patrick’s Day be upon you!

I arise today

Through a mighty strength, the invocation of the Trinity,

Through the belief in the threeness,

Through confession of the oneness

Of the Creator of Creation.

I arise today

Through the strength of Christ’s birth with his baptism,

Through the strength of his crucifixion with his burial,

Through the strength of his resurrection with his ascension,

Through the strength of his descent for the judgment of Doom.

I arise today

Through the strength of the love of Cherubim,

In obedience of angels,

In the service of archangels,

In hope of resurrection to meet with reward,

In prayers of patriarchs,

In predictions of prophets,

In preaching of apostles,

In faith of confessors,

In innocence of holy virgins,

In deeds of righteous men.

I arise today

Through the strength of heaven:

Light of sun,

Radiance of moon,

Splendor of fire,

Speed of lightning,

Swiftness of wind,

Depth of sea,

Stability of earth,

Firmness of rock.

I arise today

Through God’s strength to pilot me:

God’s might to uphold me,

God’s wisdom to guide me,

God’s eye to look before me,

God’s ear to hear me,

God’s word to speak for me,

God’s hand to guard me,

God’s way to lie before me,

God’s shield to protect me,

God’s host to save me

From snares of devils,

From temptations of vices,

From everyone who shall wish me ill,

Afar and anear,

Alone and in multitude.

I summon today all these powers between me and those evils,

Against every cruel merciless power that may oppose my body and soul,

Against incantations of false prophets,

Against black laws of pagandom

Against false laws of heretics,

Against craft of idolatry,

Against spells of witches and smiths and wizards,

Against every knowledge that corrupts man’s body and soul.

Christ to shield me today

Against poison, against burning,

Against drowning, against wounding,

So that there may come to me abundance of reward.

Christ with me, Christ before me, Christ behind me,

Christ in me, Christ beneath me, Christ above me,

Christ on my right, Christ on my left,

Christ when I lie down, Christ when I sit down, Christ when I arise,

Christ in the heart of every man who thinks of me,

Christ in the mouth of everyone who speaks of me,

Christ in every eye that sees me,

Christ in every ear that hears me.

I arise today

Through a mighty strength, the invocation of the Trinity,

Through belief in the threeness,

Through confession of the oneness,

Of the Creator of Creation.

Not long ago, Newsweek magazine published a cover

Not long ago, Newsweek magazine published a cover

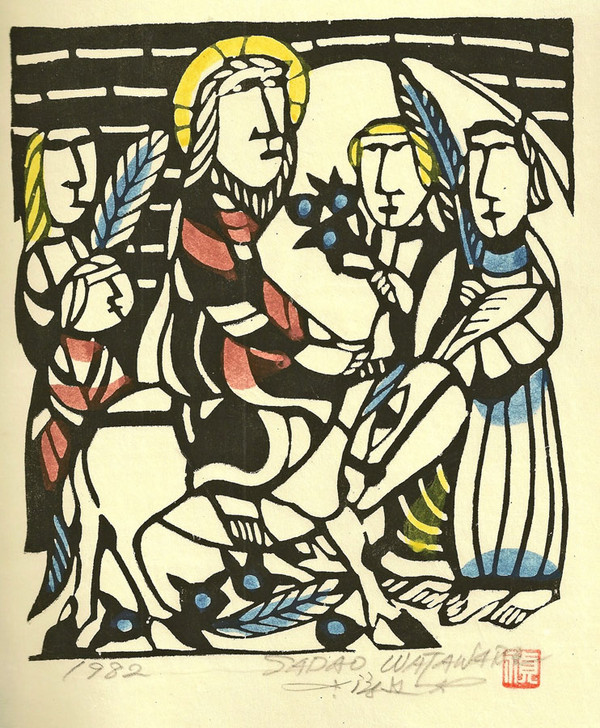

In Western Christianity, January 6 is the Feast of the Epiphany–a celebration of the light of God shining into the world with the birth of Christ. In particular, this day is associated with

In Western Christianity, January 6 is the Feast of the Epiphany–a celebration of the light of God shining into the world with the birth of Christ. In particular, this day is associated with

The website “

The website “