:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-1127577455-af4de78e939a40d9b37032ef9e24fd8a.jpg)

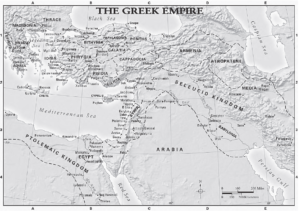

By 332 BCE, Alexander the Great had conquered most of the ancient Near East. His kingdom stretched from north Africa to India. But Alexander died, suddenly and unexpectedly, scarcely ten years later, leaving behind no heir. So Alexander’s four leading generals divided the empire among them. Cassander, who claimed Macedonia, and Lysimachus, who claimed Thrace (that is, Greece and Asia Minor), play no role in Israel’s story. However, the heirs of Ptolemy, who ruled in Egypt, and Seleucus, who ruled in Syria, figure prominently.

Through the following generations, the descendants of these two Greek generals, called the Ptolemies and the Seleucids, squabbled for control of Palestine. As long as the Ptolemies of Egypt were in control, the Jews of Palestine were left alone. However, in 200 BCE Antiochus III, the reigning Seleucid, conquered Palestine. At first, little changed. But when Antiochus IV Epiphanes came to power in 175 BCE, he began to intervene drastically in Jewish life (1 Maccabees 1:20-64; compare Daniel 7:25; 11:29-39).

Antiochus IV appointed a high priest of his own choosing (ominously named Jason–clearly not a Hebrew name!) in Jerusalem, and gave his support to those in the Jerusalem aristocracy who favored the new Greek ways. This may have been part of Antiochus’ campaign to unify his kingdom under Greek culture and religion. Or, he may have sought to control the temple in order to get his hands on the Jerusalem temple treasury. But when pious Jews resisted, he used cruder methods. In 167 BCE, an altar to Zeus, chief god of the Greeks, was set up in the Jerusalem temple. On this altar was sacrificed an animal sacred to Zeus: the pig.

Similar altars, and similar sacrifices, were ordered established throughout the land. It became illegal to circumcise male children, to observe the Sabbath or any of the other festivals, to teach or even to read the Law, and those who resisted were horrifically persecuted.

The traditional Hanukkah song “Hayo Hayah” recalls the story:

Let us remember reign of terror, reign of terror

King who murdered, pain forever, pain forever

Who then? Antiochus, Antiochus.

The blood he spilled, Jerusalem, Jerusalem

So many killed, gone all of them, gone all of them

Who then? Antiochus, Antiochus.

Our hearts he broke, he burned the torah, burned the torah

Ash and smoke, the crushed menorah, crushed menorah

Who then? Antiochus, Antiochus.

Arise our hero, Judah save us, Judah save us

Prize so dear, the vict’ry gave us, freedom gave us

Who then? Maccabeus, Maccabeus.

Oh sing our songs and praise the torah, praise the torah

Right the wrongs and light menorah, light menorah

When then? Chanukah, Chanukah.

Jerusalem was liberated in 164 BCE by an army of Jewish guerrillas led by Judah Maccabee (likely, “Judah the Hammer”!), or Judas Maccabeus (1 Maccabees 4:36-61). Following the liberation of Jerusalem, he summoned faithful priests to reconsecrate the temple and its altar, defiled by the idolatrous rites that had been performed there under Antiochus’ rule. But, according to the tradition, they hit a snag. Talmud says:

For when the Greeks entered the Temple, they defiled all the oils therein, and when the Hasmonean dynasty prevailed against and defeated them, they made search and found only one cruse of oil which lay with the seal of the High Priest, but which contained sufficient for one day’s lighting only; yet a miracle was wrought therein and they lit [the lamp] therewith for eight days. The following year these [days] were appointed a Festival with [the recital of] Hallel and thanksgiving [b. Shabbat 21b].

The dreidel game traditionally played during Hanukkah becomes another way of recalling the miracle of the lamps:

Each side of the dreidel bears a letter of the Hebrew alphabet: נ (nun), ג (gimel), ה (hei), ש (shin). These letters are translated in Yiddish to a mnemonic for the rules of a gambling game played with a dreidel: nun stands for the word נישט (nisht, “not”, meaning “nothing”), gimel for גאַנץ (gants, “entire, whole”), hei for האַלב (halb, “half”), and shin for שטעלן אַרײַן (shtel arayn, “put in”). However, according to folk etymology, they represent the Hebrew phrase נֵס גָּדוֹל הָיָה שָׁם (nes gadól hayá sham, “a great miracle happened there”).

Much of this history is also related, if symbolically, in the book of Daniel–although with a decidedly different ending! The conquests of Alexander, his death, and the division of his kingdom are recounted in Daniel 8. That Greek empire appears to be the focus of the night vision of Daniel 7. Four chimerical beasts representing conquering kingdoms rise out of the sea— an ancient symbol of chaos (see Isa 27:1; 51:9-10). The first three at least resemble actual animals: a lion, a bear, a leopard. But the fourth is unlike anything on earth: “terrifying and hideous, with extraordinary power,” it has ten horns and iron teeth (Dan 7:7).

In Zechariah 1:18-21 (2:1-4 in Hebrew), four horns represent the four powers “that scattered Judah, Israel, and Jerusalem” (1:19 [2:2]; likely Egypt, Assyria, Babylon, and Persia). So too in Daniel 7:1– 8, four is the number of Israel’s oppressors, although a different four: evidently Babylon, Media, Persia, with the fourth and last being Greece. This reinterpretation of images is common in apocalypses like Daniel.

Readers in later contexts have reinterpreted this vision in other ways; indeed, the first- century CE Jewish apocalypse 4 Ezra reads, “The eagle [a common symbol of Rome] you saw rising from the sea is the fourth kingdom. It appeared in a vision to your brother Daniel,but it wasn’t interpreted for him as I now interpret it for you or have shown it to you” (2 Esd 12:11– 12). 4 Ezra and the book of Revelation (Rev 17:9) alike understood Daniel’s fourth beast to be, not Greece, but Rome!

Among the ten horns of this fourth beast, which in the original context likely represented the kings of Alexander’s Greek empire, is a little horn “that bragged and bragged” (Dan 7:8; the Aramaic is milallil rabrĕbān, or “talking big”)–Antiochus IV Epiphanes (see also Dan 8:9-14; 23– 25). This one, Daniel is told, “shall speak words against the Most High, shall wear out the holy ones of the Most High, and shall attempt to change the ritual calendar and the law” (Dan 7:25 NRSVue)— all of which Antiochus did. But not much time remained to this arrogant ruler: only “a time, two times, and half a time,” or three and a half years (Dan 7:25; also variously described in Dan 8:14; 9:27; 12:7, 11-12).

Setting aside the animal imagery of Daniel 7–8, Daniel 10:1–11:39 speaks more straightforwardly about Antiochus’ final days. Antiochus’ terrible sacrilege–the sacrifice of an unclean animal to an alien god–is the “desolating monstrosity” of Daniel 11:31 (in the KJV, “the abomination that maketh desolate;” for later interpretations of this Danielic image, see Matt 24:15; Mark 13:14). Daniel 11:40-43 predicts steadily greater victories for Antiochus–until suddenly “reports from the east and north will alarm him, and in a great rage he will set off to devastate and destroy many” (Dan 11:44). Then, preparing to return to Syria, Antiochus will camp in Palestine, where the archangel Michael will fall upon him with the heavenly armies and destroy him, ushering in the resurrection of the dead and the end of the world (Dan 12:1-3).

Antiochus actually died in the course of his campaign against Persia, in 164 BCE. Daniel does not describe this, nor does it mention the Maccabean revolt: likely because the book was completed sometime between 167 (the date of the “desolating monstrosity”) and 164 BCE. Although Antiochus’ oppressive rule ended in the mid-second century BCE, the world did not. As we have seen, later Jewish and Christian readers identified Daniel’s fourth kingdom with Rome (2 Esdras 12:10-12; Rev 17:9): but the world did not end with the fall of Rome, either.

Indeed, the many predictions in the New Testament that the end of the world would come soon (for example, Mark 13:30; 1 Cor 7:29-31; Rev 22:12, 20) clearly were not realized. Within the New Testament itself, this delay is seen as a sign of God’s grace. The epistle reading for this Sunday, the second Sunday in Advent, declares “The Lord isn’t slow to keep his promise, as some think of slowness, but he is patient toward you, not wanting anyone to perish but all to change their hearts and lives” (2 Peter 3:9).

It is finally Jesus himself who puts to rest the pretense that, if we are only clever enough, we can read our future in the pages of Scripture: “But nobody knows when that day or hour will come, not the angels in heaven and not the Son. Only the Father knows” (Mark 13:32). We are called, not to be clever, but to be ready!

In all the generations since, the promise of God’s deliverance has been continually re-read, and applied to new situations, in the confidence that God’s faithfulness will prevail over every oppressor. No matter how powerless we may feel, it is in that same confidence that we can read these passages today, sharing the confidence of John the Baptist:

“One stronger than I am is coming after me. I’m not even worthy to bend over and loosen the strap of his sandals. I baptize you with water, but he will baptize you with the Holy Spirit.”(Mark 1:7-8)

Trusting in his wisdom and might, baptized with God’s spirit, we can face the trials of our time, and of any time! Chanukkah sameach–a joyous Hanukkah and a blessed Advent to us all!