In the account of Pentecost in Acts 2:1-21, Jesus’ followers were waiting together in Jerusalem as he had commanded them, praying in an upper room, when “They were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other languages as the Spirit enabled them to speak” (Acts 2:4). Boiling out of that room and into the streets, they met Jewish pilgrims from all over the Roman world, who had come to Jerusalem for Pentecost. These visitors discovered, to their astonishment, that they could understand Jesus’ Galilean followers perfectly:

Look, aren’t all the people who are speaking Galileans, every one of them? How then can each of us hear them speaking in our native language? Parthians, Medes, and Elamites; as well as residents of Mesopotamia, Judea, and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the regions of Libya bordering Cyrene; and visitors from Rome (both Jews and converts to Judaism), Cretans and Arabs—we hear them declaring the mighty works of God in our own languages! (Acts 2:7-11).

As many readers of this passage have realized, Luke’s account of Pentecost alludes to the Babel story in Genesis 11:1-9. Traditional readings of the Tower of Babel story see it as a warning against unchecked ambition, or hubris. The sin of Babel is the tower, with which they sought to reach the heavens on their own. It is to halt this prideful ambition that God curses them by confusing their languages, stopping the construction and forcing them to divide into language groups and scatter. We sometimes refer to the profusion of the world’s languages and the scattering of humanity as the “curse of Babel,” and so to the Spirit’s gift of tongues at Pentecost as undoing that curse.

But as Theodore Hiebert has observed (“The Tower of Babel and the Origin of the World’s Cultures,” Journal of Biblical Literature 126 [2007]: 29-58), that traditional reading misses the reason the text of Genesis itself gives for building the city and the tower:

But as Theodore Hiebert has observed (“The Tower of Babel and the Origin of the World’s Cultures,” Journal of Biblical Literature 126 [2007]: 29-58), that traditional reading misses the reason the text of Genesis itself gives for building the city and the tower:

Come, let’s build for ourselves a city and a tower with its top in the sky, and let’s make a name for ourselves so that we won’t be dispersed over all the earth (Gen 11:4)

Sure enough, when God decides to act (Gen 11:5-7), God says nothing about the tower, or hubris—or indeed, about punishment. God acts because the people are about to succeed in their goal of remaining “one people” with “one language,” so that “all that they plan to do will be possible for them.” This is neither a story condemning the sin of unchecked ambition, nor an account of divine punishment for that sin. It is about God stepping in to ensure difference and diversity, just as humans are about to succeed in enforcing sameness.

Why does God do this? Perhaps because, as Argentinian Methodist theologian José Míguez Bonino wrote,

Why does God do this? Perhaps because, as Argentinian Methodist theologian José Míguez Bonino wrote,

God’s intention is a diverse humanity that can find its unity not in the domination of one city, one tower, or one language but in the ‘blessing for all the families of the earth’ (Genesis 12:3)” (“Genesis 11:1-9: A Latin American Perspective,” in Return to Babel: Global Perspectives on the Bible, ed. Priscilla Pope-Levison and John R. Levison [Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1999], 15-16).

Racial and cultural diversity is not a problem to be overcome. It is a gift of God, to be celebrated and embraced. By squelching difference, the people of Babel were standing in the way of the diversity of expression that is God’s intent for human beings.

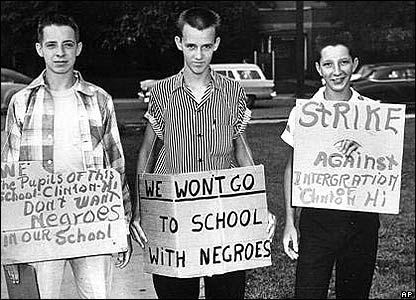

In 1956, Rev. W. A. Criswell, pastor of First Baptist Church in Dallas, Texas—at that time the largest Baptist church in the world—was invited to address the General Assembly of the South Carolina legislature on the subject of racial segregation. In his cringingly self-revealing remarks, Criswell condemned

scantling good-for-nothing fellows who are trying to upset all the things that we love as good old Southern people and good old Southern Baptists. . . . Don’t force me by law, by statute, by Supreme Court decision. . . to cross over in those intimate things where I don’t want to go. . . Let me have my church. Let me have my school. Let me have my friends (cited in Robert P. Jones, The End of White Christian America [New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016], 167).

Rev. Criswell could just as well have spoken for the First Church of Babel. The denizens of that place built their city and their tower to ensure that they would stay together homogeneously: “so that we won’t be dispersed over all the earth” (Genesis 11:4). But being “dispersed over all the earth” was exactly what God intended for humanity! The old priestly traditions in Genesis state this plainly. The priestly accounts of creation and flood alike declare that humanity was to “fill the earth” (Genesis 1:28; 9:1). As the Table of Nations in Genesis 10 concretely describes, this meant not only being geographically scattered, but ethnically and culturally diverse. The real curse of Babel is not being scattered abroad. It is staying where we are comfortable and unchallenged, in “my church,” “my school,” with “my friends.” Babel itself, in its safe, comfortable, stultifying sameness, is the curse.

Please notice that Luke does not say that the people all started speaking the same language—that their cultural and ethnic distinctiveness was denied or undone. The Spirit does not return them to “one language and the same words” (Gen 11:1). Instead, each group hears God’s praise in its own language.

In Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED Talk, “The Danger of a Single Story,” she relates her first encounter with her first college roommate, in America:

She asked where I had learned to speak English so well, and was confused when I said that Nigeria happened to have English as its official language. She asked if she could listen to what she called my ‘tribal music,’ and was consequently very disappointed when I produced my tape of Mariah Carey. . . . My roommate had a single story of Africa: a single story of catastrophe. In this single story, there was no possibility of Africans being similar to her in any way, no possibility of feelings more complex than pity, no possibility of a connection as human equals.

We should not be surprised that the members of the Pentecost crowd all hear the Gospel in their own languages. The entire Bible warns us against, and models for us how to escape, the danger of the single story. Scripture rarely gives us a single story about anything! At the beginning of our Bible, we find two different accounts of the creation of the world: one in Genesis 1:1—2:4a, and another in Genesis 2:4b-25. Our New Testament opens with four gospels, presenting four quite different accounts of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection.

Scripture itself calls for us to listen with open ears and open hearts for the truth told, not as a single story, but as a chorus of voices. Sometimes those voices are in harmony, sometimes they are in dissonance, but always they are lifted in praise to the God who remembers all our stories, the comedies and tragedies alike, and catches them up together in love, forgiveness, and grace. Friends, may we honor the Spirit’s gift of Pentecost by welcoming one another, and listening to one another, in all our diversity.