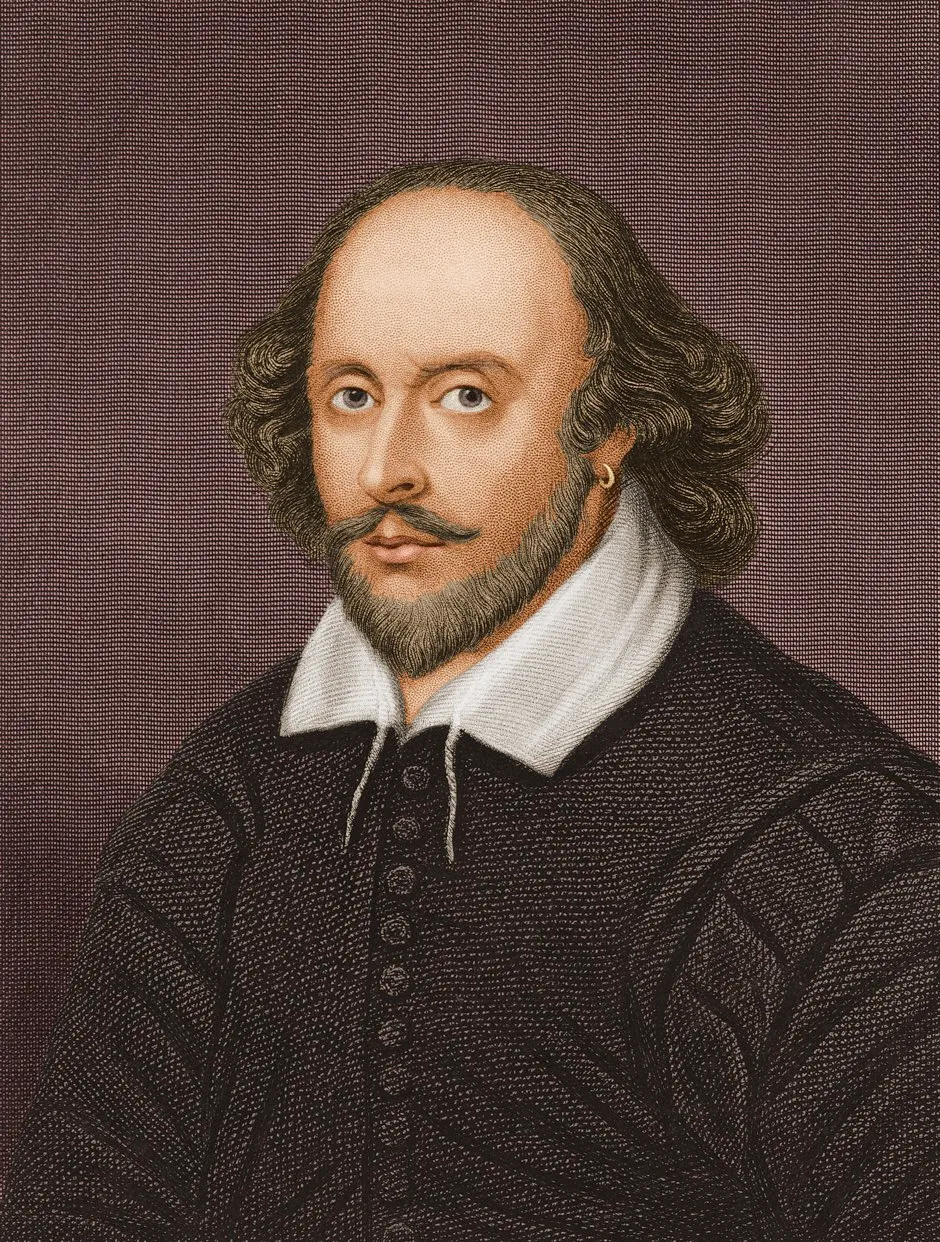

Shakespeare’s Sonnet 130 is an extraordinarily odd love poem! Indeed, until the last two lines, we may well think that he is insulting rather than praising his (unnamed) mistress. With those final lines declaring his love, and his beloved’s rarity, Shakespeare’s point becomes clear. He is lampooning the hackneyed conventions of romantic poetry in his day, declaring them incapable of expressing true love, rather than idealized infatuation. Metaphors, taken literally, become nonsense: hence, “false compare.”

Rather like Sonnet 130, the Song of Songs (often called the Song of Solomon) seems to us a very odd love song–but in this case, it is the metaphors themselves that are obscure. For example: in our time, and in our Western culture, it seems very strange to compare a woman’s eyes to doves, or her hair to a flock of goats (Song 4:1)! Yet make no mistake: the Song of Songs is intensely erotic love poetry–just the erotic poetry of a different time and culture than ours. But even so, its passion and intimacy come through across the years.

Certainly, the Song is a very dear text to me personally, and to my beloved wife Wendy. At our wedding, our old friend Mike McKay read Song 2:10-13 from the RSV, which is still a favorite passage:

My beloved speaks and says to me:

“Arise, my love, my fair one,

and come away;

for lo, the winter is past,

the rain is over and gone.

The flowers appear on the earth,

the time of singing has come,

and the voice of the turtledove

is heard in our land.

The fig tree puts forth its figs,

and the vines are in blossom;

they give forth fragrance.

Arise, my love, my fair one,

and come away.

Inside my wedding ring, Wendy had engraved Song of Songs 5:16: “This is my beloved and this is my friend.”

As we might expect, its frank content makes the Song controversial even now (another old friend, my seminary roommate Matt Blanzy, proposed that the Song was included in the Bible so that the book would sell!). Indeed, when the canon of the Hebrew Scriptures was coming together in the first century, many questioned whether the Song should be included. Did this book indeed “defile the hands”–that is, is it a sacred text, not to be touched or handled casually? But Rabbi Akiba said, “Let no one in Israel claim that the Song of Songs does not defile the hands!”

For the whole world is not as worthy as the day on which the Song of Songs was given to Israel; for all the writings are holy but the Song of Songs is the holy of holies (Mishnah Yadayim 3.5).

The reason for this very high view of the Song was the way that this poetry was read–not as a celebration of human love, but as an allegory for divine love:

The loving relationship of Songs of Songs was reinterpreted as a metaphor for the ardent love between God and Israel, on display most dramatically during the holiday that recalls the Exodus from Egypt. Some Jews also read Song of Songs every Friday night, as a kind of renewal of the vows between God and Israel. As Rabbi Akiva passionately argued, it has become a permanent part of the Jewish canon.

Similarly, early Christians read the Song as an allegory for the love between Christ and his bride, the church (see Ephesians 5:22-33; Revelation 19:6-9; 21:9-27). Accordingly, Bernard of Clairvaux wrote 82 sermons on the Song!

Without doubt, this is a potent image, capturing something of the intensity and passion of our worship and devotion to the Lord, and of the deep, committed love of Jesus for us, love which led him to the cross. Note, though, that in the Song, the relationship between the Lover and the Beloved is not only mutual, but equal. This is clearly not true to our relationship with the Divine, where the initiative and authority are all God’s. However, we also must not conclude from the marriage metaphor that God is male.

Nor should we misread Scripture and claim for human husbands something like Divine authority over human wives! While some readers have understood Ephesians 5:22-33 to stipulate the proper roles of husband and wife (“Wives, submit yourselves unto your own husbands. . . Husbands, love your wives,” Eph 5:22, 25 KJV), the author of Ephesians, following prophetic precedent (for example, Hosea 2:16-18; Jeremiah 2:1-2), is using marriage as a metaphor for the relationship between the community of faith and its Lord. This writer’s citation of Genesis 2:24 (see Ephesians 5:31) is explicitly metaphorical, as the old NRSV made quite evident: “This is a great mystery, and I am applying it to Christ and the church” (compare Eph 5:32 NRSVue).

Shakespeare’s poetic critique of “false compare” should remind all of us, but particularly theologians and students of Scripture, not to confuse a metaphor with the reality to which it points. We are compelled to metaphor, for God is God, and not an object in the world. But whatever image of God we have in our heads, God is not that.

Our language is limited, particularly when we strive to speak of God. Can we pay close attention to what we say, understanding the power of words to wound and to heal? Can we strive in our talk about God to be faithful to the God revealed to us in Christ Jesus, who calls us, not to dominate one another, but to lives of love and service?