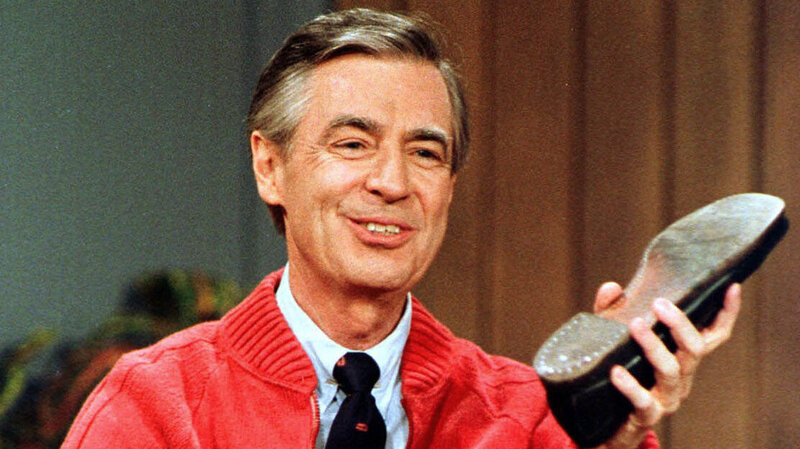

Every year on or around my birthday, October 3, I try to find as many opportunities as I can to share this bit of wonderful nonsense from Theodore Geisel–better known as Dr. Suess. Under the silliness, it carries a deep affirmation of self-worth, which reminds me of the fundamental philosophy of Pittsburgh Theological Seminary’s best-known alumnus, Mr. Fred Rogers. Every day on his television program, Mr. Rogers told every little child watching, “You are special, just for being you.”

This past week, in the seminary chapel and again in the chapel of the Allegheny jail, I shared Dr. Suess’ birthday poem at the opening of a sermon on Lamentations 3:19-26:

The memory of my suffering and homelessness is bitterness and poison.

I can’t help but remember and am depressed.

I call all this to mind—therefore, I will wait.

Certainly the faithful love of the Lord hasn’t ended; certainly God’s compassion isn’t through!

They are renewed every morning. Great is your faithfulness.

I think: The Lord is my portion! Therefore, I’ll wait for him.

The Lord is good to those who hope in him, to the person who seeks him.

It’s good to wait in silence for the Lord’s deliverance.

The hope in Dr. Suess’ poem seems to echo the hope in this passage of Scripture–but does it? After all, Lamentations (found just after Jeremiah in our Old Testament) is a grim collection of five poems mourning the fall of Judah, and the destruction of Jerusalem. There is only one hopeful word in this book, and this is it! Therefore, some would say that to preach on this passage is dishonest, as it is not representative of the book as a whole. In fact, since this passage is swallowed up by poems of despair surrounding it, the point could be that these words were ineffectual–that they provided no lasting healing or hope.

Certainly, Mr. Rogers took some flack for his message of self-affirmation. One television panel claimed that this message was “ruining kids”:

Certainly, Mr. Rogers took some flack for his message of self-affirmation. One television panel claimed that this message was “ruining kids”:

Well here’s the problem [that] gets lost in that whole self business, and the idea that being hard and having high issues for yourself, discounted. Mr. Rogers’ message was, “You’re special because you’re you.” He didn’t say, “If you want to be special, you’re going to have to work hard,” and now all these kids are growing up and they’re realizing, “Hey wait a minute, Mr. Rogers lied to me, I’m not special”

The panel decried the damage Mr. Rogers may have done to this whole crop of kids who now feel entitled just for being them. And what he says that instead of telling them, “You’re special, you’re great,” why didn’t he just say, “You know what, there’s a lot of improvement, keep working on yourself.”

The television panel’s critique may seem to some more reflective of Christian faith (and certainly more true to the overall tone of Lamentations) than Mr. Rogers’ or Dr. Suess’ message of affirmation. After all, Calvinism (if not Calvin) emphasizes our total depravity (the “T” in “TULIP“): that we have nothing in ourselves that is lovely or worthy, apart from God’s gracious election. I grew up in the sawdust-trail revivalist tradition of Christianity, in which the point of preaching often seems to be bringing its hearers to such a state of fear and guilt and self-loathing that they will run to the altar to be saved from judgment, hell, sin, and themselves: repentance as the child of despair.

But this is not the only way that Christian tradition has spoken about humanity, or about our relationship with God. In his Ladder of Divine Ascent, 5, Christian mystic St. John Climacus writes, “Repentance is the daughter of hope and the denial of despair.” Repentance is not born out of despair, but is the child of hope, and indeed the denial of despair!

Metropolitan Kallistos Ware (The Inner Kingdom [St. Vladimir Press, 2000], 45) unpacks St. John’s teaching on repentance:

It is not self-hatred but the affirmation of my true self as made in God’s image. To repent is to look, not downward at my own shortcomings, but upward at God’s love; not backward with self-reproach, but forward with trustfulness. It is to see, not what I have failed to be, but what by the grace of God I can yet become.

I think that it is no accident that those words of hope in Lamentations have been placed in the center of the book, in the middle of its longest poem. The point is that, yes, things are bad–as bad as they could possible be. But what saves us from despair is knowing that we are loved, and that God is faithful: “Certainly the faithful love of the Lord hasn’t ended; certainly God’s compassion isn’t through!

They are renewed every morning. Great is your faithfulness.” The point is not optimism, but rather hope. Optimism says, nothing bad will happen. However, hope affirms that no matter what happens, all will be well. It was that hope that caused Jews being marched to the gas chambers in the Nazi holocaust to recite, from the creed of Moses Maimonides, “I believe, I believe, with a perfect faith, I believe that Messiah will come, and though he tarry, I will expect him daily.”

Friends, I believe that it is consistent with the heart of the Gospel to claim our created goodness, and our standing as people God loves, and for whom Christ died. Looking upward to God’s love, forward with trust, we may go forth by God’s grace, transformed by Christ and empowered by the Spirit, to be the people we were created to be.

I can shout with Dr. Suess, and invite you to shout with me: “I am what I am! That’s a great thing to be. If I say so myself, HAPPY BIRTHDAY TO ME!”

AFTERWORD:

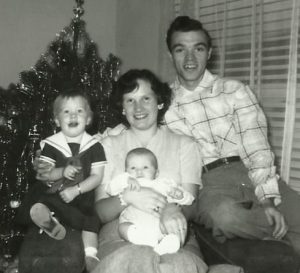

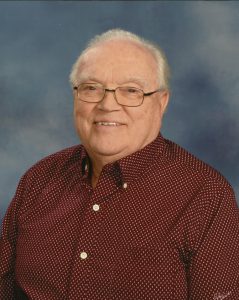

October is also the birth month of my father, Bernard Tuell. We are heading back home this weekend to celebrate his 85th with family and friends at our home church, Big Tygart UMC. God bless you and happy birthday, Daddy!