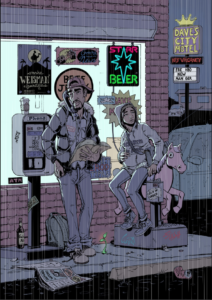

My old friend from grad school days, fellow United Methodist minister Frank Norris, posted this panel by Everett Patterson on Facebook. It is called “José y Maria.” Frank invites us to look for the many allusions to Christian art and Scripture in this image.

I have seen this piece many times, and posted it before myself, but this time, for the first time, I noticed the graffiti on the phone: “Zeke 3415-16.”

Ezekiel 34:15-16 reads, I myself will feed my flock and make them lie down. This is what the LORD God says. I will seek out the lost, bring back the strays, bind up the wounded, and strengthen the weak. But the fat and the strong I will destroy, because I will tend my sheep with justice.

The Hebrew Bible amply attests to the use of the shepherd metaphor for Israel’s rulers (for example, 2 Sam 5:2; Jer 3:15; Ezek 34:1-10; Mic 5:1-5a; Zech 10:2-3). By analogy, the LORD as king of the universe is also called a shepherd (see Ps 23; Ezek 34:11-16), an idea that lies back of the New Testament image of Jesus as the Good Shepherd in John 10 and (more disturbingly) Matthew 25:31-46, which begins,

“Now when the Human One comes in his majesty and all his angels are with him, he will sit on his majestic throne. All the nations will be gathered in front of him. He will separate them from each other, just as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats. He will put the sheep on his right side. But the goats he will put on his left.

The specific source back of Matthew’s judgment scene is also the setting of that bit of graffiti in Patterson’s panel, Ezekiel 34:11-24.

This prophetic text from the Babylonian exile is reminiscent of the far better-known Psalm 23. Here as there, the LORD causes the flock to lie down in good pasture, beside streams of waters. But the mention of the settlements in the land (“inhabited places” in the CEB; 34:13) breaks up this pastoral imagery to remind the reader that this is about Israel after all, not about sheep: God will bring the exiles home, and repopulate desolated Judah.

The last verse of this section begins as a summary of 34:11-16, reiterating God’s determination to seek out and care for the scattered sheep. But then, abruptly, the image shifts: “I will seek out the lost, bring back the strays, bind up the wounded, and strengthen the weak. But the fat and the strong I will destroy” (34:16). This statement, like the mention of settlements in 34:13, explodes the metaphor: it makes no sense for any shepherd to destroy the strong and healthy sheep!

No wonder the Greek Septuagint (LXX), the Syriac, and the Latin Vulgate all read “I will watch over” instead, assuming an original Hebrew ‘eshmor instead of ‘ashmid (“I will destroy”). The two words are nearly identical in Hebrew, where vowels are not written, and the consonants d and r look a great deal alike. It is easy to understand a scribe mistaking one for the other. The reading followed by the LXX certainly seems a better fit with the context of 34:11-16, which stresses God’s care for the flock, in striking contrast to the cruelty of the false shepherds: that is, Israel’s kings. Numerous commentators on Ezekiel (for example, Walther Zimmerli, Ezekiel 2, 208; Daniel Block, Ezekiel 25—48, 287; Leslie Allen, Ezekiel 20—48, 157) therefore follow the LXX here.

On the other hand, not only the CEB, but also NIV, NRSV, and even the KJV all stay with the Hebrew Bible here, which reads ‘ashmid (“I will destroy”)– and they are right to do so. The next phrase in Ezekiel 34:16 makes the prophet’s meaning clear: “But the fat and the strong I will destroy, because I will tend my sheep with justice.” God’s justice was seen in 34:1-10 with the punishment of the false shepherds, Israel’s past kings. But while the shepherds had certainly been guilty, the sheep are not therefore innocent! Throughout this book, Ezekiel rejects the exilic community’s claim that they are innocent victims (see, for example, 18:1-4).

In the next section, 34:17-24, God’s justice is visited on the sheep, just as it had been visited on the shepherds. Once more good theology trumps good animal husbandry, as God sides with the weak and injured over against the fat and strong (Christian readers may be reminded of the shepherd who leaves the ninety-nine unguarded in the fold to seek out the one lost lamb; Matt 18:10-14//Luke 15:3-7)! The startling introduction of this idea in 34:16 is in keeping with Ezekiel’s style elsewhere: this prophet loves to shock his audience.

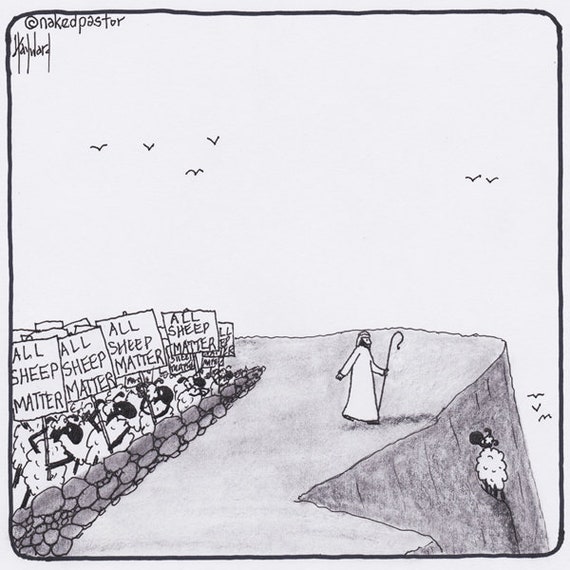

God’s judgment upon the flock falls into two parts, the accusation (34:17-19), and the pronouncement of judgment (34:20-24). The accusation opens, “As for you, my flock, the Lord God proclaims: I will judge between the rams and the bucks among the sheep and the goats” (34:17)–words that directly call to mind the judgment scene in Matthew 25 (compare 25:32).

In Matthew as in Ezekiel, the basis of the judgment is regard for the least (Matt 25:40, 45). So, in Ezekiel, the strong sheep are taken to task for selfishly and greedily trampling the pasture and muddying the water so that others cannot eat or drink (34:18-19). The point is expanded in 34:21: the strong are condemned for thrusting the weak aside.

In our own day, the gap between rich and poor is wider than it has ever been, as the lion’s share of the world’s resources is claimed by a diminishing minority of its people. The trampling of our earth and fouling of our water, through irresponsible use of this world’s resources, now threatens the entire planet through climate change, even as it robs opportunity from the most vulnerable. Ezekiel plainly states God’s place in this: on the side of the poor, and on the side of the abused land. God declares, “I will rescue my flock so that they will never again be prey” (34:22).

If you are wondering what any of this has to do with the season of Advent, or with the birth of our Lord, may I remind you that the alternate Psalm for this coming Sunday is Luke’s Song of Mary (Luke 1:46-55), often called the Magnificat after its opening in Latin, Magnificat anima mea Dominum (in the KJV, “My soul doth magnify the Lord;” the Presbyterian hymnal has a lovely and vigorous setting of this passage!). Here is the whole song:

If you are wondering what any of this has to do with the season of Advent, or with the birth of our Lord, may I remind you that the alternate Psalm for this coming Sunday is Luke’s Song of Mary (Luke 1:46-55), often called the Magnificat after its opening in Latin, Magnificat anima mea Dominum (in the KJV, “My soul doth magnify the Lord;” the Presbyterian hymnal has a lovely and vigorous setting of this passage!). Here is the whole song:

With all my heart I glorify the Lord!

In the depths of who I am I rejoice in God my savior.

He has looked with favor on the low status of his servant.

Look! From now on, everyone will consider me highly favored

because the mighty one has done great things for me.

Holy is his name.

He shows mercy to everyone,

from one generation to the next,

who honors him as God.

He has shown strength with his arm.

He has scattered those with arrogant thoughts and proud inclinations.

He has pulled the powerful down from their thrones

and lifted up the lowly.

He has filled the hungry with good things

and sent the rich away empty-handed.

He has come to the aid of his servant Israel,

remembering his mercy,

just as he promised to our ancestors,

to Abraham and to Abraham’s descendants forever.

In many Christian traditions, Advent is a penitential season (Orthodox call it “Little Lent”!). Certainly, it is right that, in preparation for Christ’s coming, we search our own hearts and lives. Mary’s song, like Ezekiel’s, reminds us that God takes sides in our world, and challenges us to ask what side we are on.

AFTERWORD:

Having grown up in a non-liturgical church (I don’t believe I knew about the seasons of the church year, apart from Easter and Christmas, until college), I always wondered why, in some traditions, the candle for the third Sunday of Advent is pink, not purple.

In the Roman Catholic liturgical calendar, the third Sunday in Advent is Gaudete Sunday, so called for the first word in the Latin introit for this day, “Gaudete in Domino semper“–from Philippians 4:4-5 (KJV): “Rejoice in the Lord always: and again I say, Rejoice.”

The website “About Catholicism” explains the rose-colored candle, and vestments, for this day:

Like Lent, Advent is a penitential season, so the priest normally wears purple vestments. But on Gaudete Sunday, having passed the midpoint of Advent, the Church lightens the mood a little, and the priest may wear rose vestments. The change in color provides us with encouragement to continue our spiritual preparation—especially prayer and fasting—for Christmas.

Gaudete Sunday means that the time of waiting and preparation is nearly over–that Christmas, and more importantly, Christ, is on the way! The message of the rose-colored candle, then, is hope. Hold on.