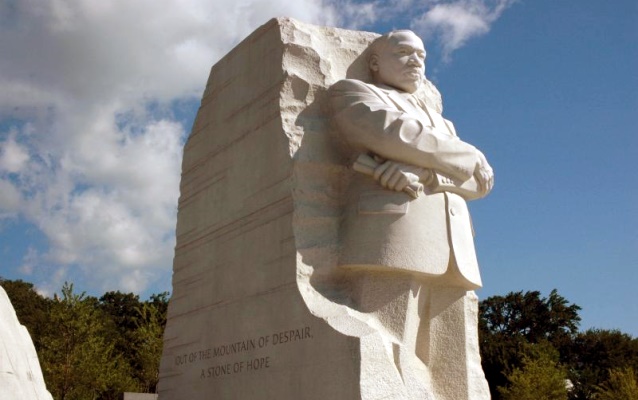

In most of the nation, today is Martin Luther King, Jr. Day: a day rightly dedicated to celebrating the legacy of our greatest civil rights leader. It is also right that a monument to Dr. King, dedicated on October 16, 2011, stands in Washington, D.C. among the memorials to other American heroes in that city of monuments. But honoring the hero may mean losing the man. Perhaps it was inevitable that honor and recognition would mute King’s radical call to justice, particularly to racial justice; that as King’s national stature grew, his historical message would be blunted, even obscured.

So, as Newsweek magazine reported yesterday, “Vice President Mike Pence compared Donald Trump to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. . . . claiming both leaders have inspired Americans to change through the legislative process.”

“Honestly, you know, the hearts and minds of the American people today are thinking a lot about it being the weekend we are remembering the life and the work of Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. One of my favorite quotes from Dr. King was, ‘Now is the time to make real the the promises of democracy,’” he said, quoting a passage from Dr. King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

Pence continued on to argue that like MLK, Trump has also “inspired us to change.” “You think of how he changed America, he inspired us to change through the legislative process, to become a more perfect union,” he said. “That’s exactly what President Trump is calling on the Congress to do, come to the table in a spirit of good faith.”

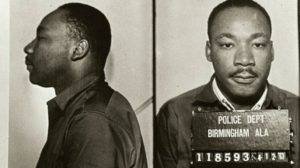

When white Americans have grown so comfortable with Martin Luther King, Jr. as to believe it appropriate to identify him with the very epitome of white privilege, in service of so racist a project as the border wall, it is clearly long past time for us to remember that Dr. King stood for, marched for, was jailed for, and died for, justice and equality. He was, by his own free admission, an extremist! In his “Letter From a Birmingham Jail,” he wrote:

I have tried to say that this normal and healthy discontent can be channeled into the creative outlet of nonviolent direct action. And now this approach is being termed extremist. But though I was initially disappointed at being categorized as an extremist, as I continued to think about the matter I gradually gained a measure of satisfaction from the label. Was not Jesus an extremist for love: “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you.” Was not Amos an extremist for justice: “Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like an ever flowing stream.” Was not Paul an extremist for the Christian gospel: “I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.” Was not Martin Luther an extremist: “Here I stand; I cannot do otherwise, so help me God.” And John Bunyan: “I will stay in jail to the end of my days before I make a butchery of my conscience.” And Abraham Lincoln: “This nation cannot survive half slave and half free.” And Thomas Jefferson: “We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal . . .” So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice? In that dramatic scene on Calvary’s hill three men were crucified. We must never forget that all three were crucified for the same crime–the crime of extremism. Two were extremists for immorality, and thus fell below their environment. The other, Jesus Christ, was an extremist for love, truth and goodness, and thereby rose above his environment. Perhaps the South, the nation and the world are in dire need of creative extremists.

Dr. King was in jail, in Birmingham, for leading sit-ins, marches, and protests of racial discrimination in that city. While in jail, he learned of an open letter published in Birmingham area papers, called “A Call for Unity”—signed by eight prominent white Alabama clergymen (including, to my shame, two Methodist bishops). The letter bemoans a “series of demonstrations by some of our Negro citizens, directed and led in part by outsiders,” and says, “We… strongly urge our own Negro community to withdraw support from these demonstrations, and to unite locally in working peacefully for a better Birmingham. When rights are consistently denied, a cause should be pressed in the courts and in negotiations among local leaders, and not in the streets.”

Dr. King wrote his famous letter in response to these white Christian leaders, who evidently preferred “a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.” Prophetically, King wrote of the church in his own day–and sadly, in ours:

There was a time when the church was very powerful–in the time when the early Christians rejoiced at being deemed worthy to suffer for what they believed. In those days the church was not merely a thermometer that recorded the ideas and principles of popular opinion; it was a thermostat that transformed the mores of society. Whenever the early Christians entered a town, the people in power became disturbed and immediately sought to convict the Christians for being “disturbers of the peace” and “outside agitators.”‘ But the Christians pressed on, in the conviction that they were “a colony of heaven,” called to obey God rather than man. Small in number, they were big in commitment. They were too God-intoxicated to be “astronomically intimidated.” By their effort and example they brought an end to such ancient evils as infanticide and gladiatorial contests. Things are different now. So often the contemporary church is a weak, ineffectual voice with an uncertain sound. So often it is an archdefender of the status quo. Far from being disturbed by the presence of the church, the power structure of the average community is consoled by the church’s silent–and often even vocal–sanction of things as they are.

But the judgment of God is upon the church as never before. If today’s church does not recapture the sacrificial spirit of the early church, it will lose its authenticity, forfeit the loyalty of millions, and be dismissed as an irrelevant social club with no meaning for the twentieth century. Every day I meet young people whose disappointment with the church has turned into outright disgust.

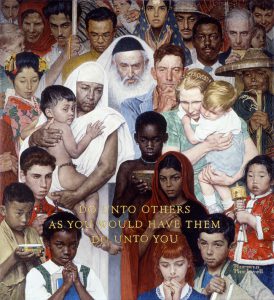

A truly Christian view of racial justice must begin as Christian Scripture begins: with a radical affirmation of human unity, dignity, and equality. As Dr. George D. Kelsey, mentor to Martin Luther King, Jr. at Morehouse College, understood (George D. Kelsey, Racism and the Christian Understanding of Man [New York: Scribner, 1965]), the biblical confession that we are all descended from Adam and Eve means that there is one single human family. Throughout his theology and ethics, Dr. Kelsey “pointed to the Genesis creation narrative and its assertion of a singular and common ancestry of all humanity” (Torin Alexander, “World/Creation in African American Theology,” in The Oxford Handbook of African American Theology, ed. Katie G. Cannon and Anthony B. Pinn [New York: Oxford University, 2014], 186.)

Close reading of Genesis 1 underlines that insight. On Day Three, when God invites the earth to “put forth vegetation” (Genesis 1:11), the earth produces “plants yielding seed of every kind, and trees of every kind bearing fruit with the seed in it” (Genesis 1:12). Similarly, on Day Five, God creates “every living creature that moves, of every kind, with which the waters swarm, and every winged bird of every kind” (Gen 1:21). On Day Six, God again invites the earth, “bring forth living creatures of every kind: cattle and creeping things and wild animals of the earth of every kind” (Gen 1:24). Every form of life God makes comes in kinds–except one.

When we arrive at the creation of humanity at the end of Day Six, nothing is said of there being any “kinds” of people (see Phyllis A. Bird, “‘Male and Female He Created Them’: Gen 1:27b in the Context of the Priestly Account of Creation,” Harvard Theological Review 74 [1981]: 146). This is certainly not because the ancient Israelites were ignorant of other races and cultures: Palestine was a crossroads of ancient civilizations. The Israelites were fully aware of Africans and Asians, people of varying ethnicities, speaking a host of languages, coming from a variety of cultures. Yet Israel does not distinguish among these races and nations, as though some are more human than others. Certainly, Genesis does not identify the Israelites as human, and their neighbors as something less. This is a remarkable confession, rejecting every form of racism and jingoistic nationalism–including our own.

As Scripture sadly but faithfully bears witness, Israel was not always faithful to this insight. But it is an insight that recurs again and again—and one that the church in our day must reclaim. For while Genesis identifies no “kinds” of people, we have been swift to make up that lack, hastening to identify all sorts of folk as outsiders, strangers, aliens, who are not welcome in our communities. Especially on this day in honor of that “creative extremist,” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., may God help us to see and repent of this sin, and to love all whom God loves, as we have ourselves been loved.