Two households, both alike in dignity, in fair Verona where we lay our scene. . .

In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.

Beginnings matter. Certainly Shakespeare, and Melville, and Tolkien (not to mention Snoopy) knew this well! The opening lines of a work can pull us in and compel us to keep reading, or leave us cold, and turn us away.

All the more interesting, then, that the Psalm for this past Sunday was the first Psalm. Indeed, in Codex Leningradensis, one of the oldest and certainly most complete texts of the Hebrew Bible we have, this psalm is unnumbered, set apart as the heading to the numbered psalms that follow. Many interpreters have proposed that Psalm 1 was composed for this very place and purpose: to open the book of Psalms.

So, how does the Psalter begin?

Happy are those

who do not follow the advice of the wicked,

or take the path that sinners tread,

or sit in the seat of scoffers;

but their delight is in the law of the Lord,

and on his law they meditate day and night (Ps 1:1-2).

As James Luther Mays observed, “The Book of Psalms begins with a beatitude. Not a prayer or a hymn, but a statement about human existence” (Psalms, Interpretation [Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1994], p. 40).

![]()

St. Athanasius famously observed that while the rest of Scripture speaks to us, the Psalms speak for us. He wrote:

Within [the Psalter] are represented and portrayed in all their great variety the movements of the human soul. . . . In the Psalter you learn about yourself (from “To Marcellinus on the Interpretation of the Psalms”).

So, what do we learn from this Psalm about ourselves, as we are and as we might become? On its face, Psalm 1 contrasts two groups: the wicked (Hebrew resha’im) and the righteous (tsadiqim). But the Psalm is actually not interested in the wicked, who are defined only negatively: by their opposition to the righteous, who do not follow their way, or sit in their councils (1:1), just as the wicked themselves “will not stand in the judgment, nor sinners in the congregation of the righteous” (1:5).

The righteous, by contrast, are positively defined by their immersion in Torah (the Hebrew word translated “law” in Psalm 1:1-2), which in Jewish tradition can refer to the first five books of the Bible, also called the Five Books of Moses. Psalm 1 affirms that God’s Torah is the source and ground of blessing. This emphasis on Torah reflects the structure of the Psalter, which is divided by four doxologies (Pss 41:13; 72:18-19; 89:52; and 106:48) into five books, reminiscent of the Torah.

Jerome Creach proposes that in Psalm 1, Torah refers not only to the written Torah of Moses, but also to the Psalter itself: “The Psalms are a part of the pluriform expression of divine instruction by which the righteous find a secure destiny, hope for their living” (Jerome Creach, The Destiny of the Righteous in the Psalms [St. Louis: Chalice, 2008], p. 139).

Certainly, the language of Psalm 1 does not permit a legalistic understanding either of righteousness or of Torah. In Deuteronomy 15:5, by comparison, Israel is enjoined to “obey [Hebrew shama’ beqol; literally, “hear the voice of”] the LORD your God by diligently observing [Hebrew shamar] this entire commandment [Hebrew mitswah] that I command you today” (cf. also Lev 26:14). None of this legal vocabulary appears in Psalm 1.

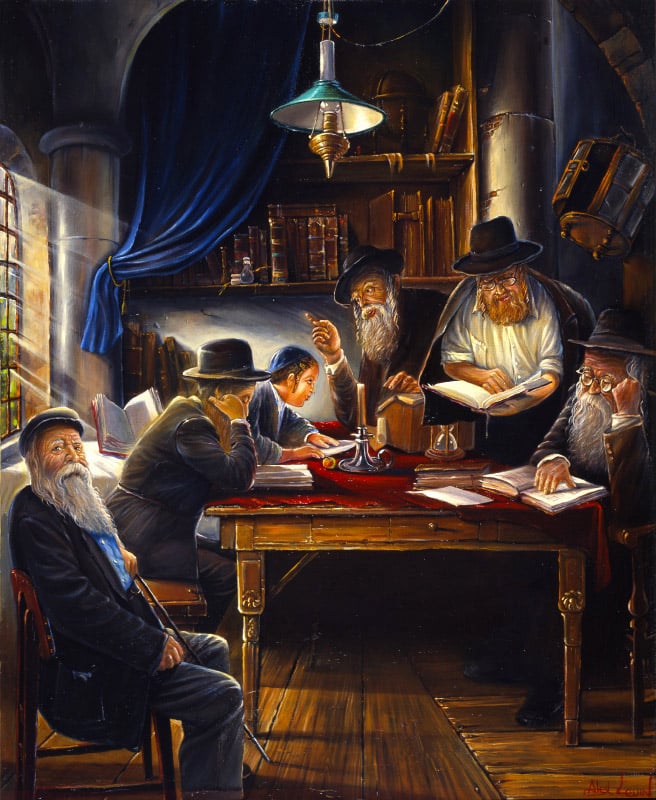

Instead, the righteous are here said to “delight” in the LORD’s Torah (Hebrew chapets, perhaps better rendered “desire”). They “meditate” upon God’s Torah day and night (Ps 1:2). Here, the verb hagah actually means “murmur,” implying constant, repetitive study and recitation–something particularly appropriate to my own setting here at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary.

Despite the traditional translation of the Hebrew word torah as “law,” the word actually means “teaching.” Here in Psalm 1, certainly, Torah is not about legalism, but about living, fully and well! Focus on divine instruction yields for the righteous happiness (Ps 1:1) and stability:

They are like trees

planted by streams of water,

which yield their fruit in its season,

and their leaves do not wither.

In all that they do, they prosper (Ps 1:3).

This arboreal imagery emphasizes both the stability and fruitfulness of the righteous. To shun this divine instruction is to be “like chaff that the wind drives away” (1:4): empty husks, dry, lifeless, fruitless, and rootless.

In contrast, the righteous are defined concretely, by their relentless pursuit of Torah. Therefore, “the LORD watches over the way of the righteous” (Ps 1:6). The verb translated “watches over” in the NRSV of Psalm 1:6 is yada’, that is, “know.” In Hebrew, “knowing” has to do not simply with intellectual grasp, but with relationship. Those who desire to know God, who seek out and meditate upon God’s instruction, are in turn known by God.

In the first Psalm, the destiny of the righteous is to know, and be known, by God—to enter into a relationship with the Divine; to become like trees in God’s garden, drawing life from God and bearing fruit for God. As I and my students begin this new year in this place of study, I pray that we will immerse ourselves in the pursuit of God’s Torah–God’s instruction, God’s way of life. Scripture assures us that such seekers will not seek in vain; as Jesus promises in the Sermon on the Mount, “Ask, and it will be given you; search, and you will find; knock, and the door will be opened for you” (Matt 7:7).