Saturday, March 11

No text is given for today’s devotional, because today we reflect, not on what Genesis 1:1—2:4a says, but on something that it doesn’t say! Until the creation of human being, all living things in this account come in “kinds.” On Day Three, when God invites the earth to “put forth vegetation” (Genesis 1:11), the earth produces “plants yielding seed of every kind, and trees of every kind bearing fruit with the seed in it” (Genesis 1:12). Similarly, on Day Five, God creates “every living creature that moves, of every kind, with which the waters swarm, and every winged bird of every kind” (Gen 1:21). On Day Six, God again invites the earth, “bring forth living creatures of every kind: cattle and creeping things and wild animals of the earth of every kind” (Gen 1:24).

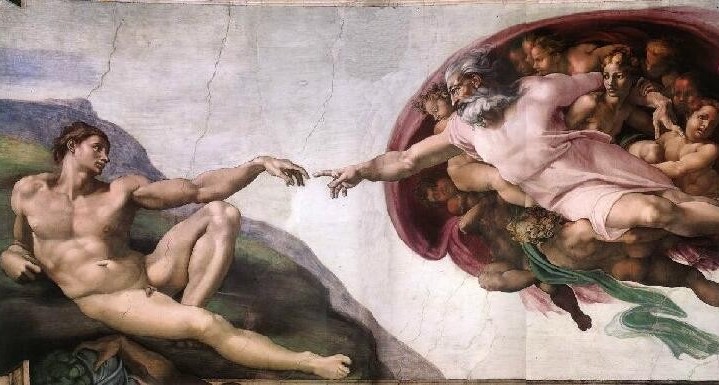

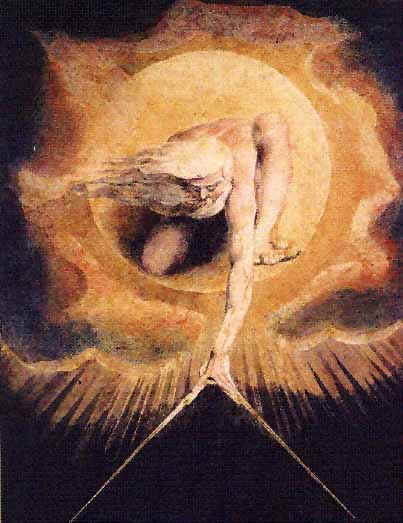

When we arrive at the creation of humanity at the end of Day Six, however, nothing is said of there being any “kinds” of people (see Phyllis A. Bird, “ ‘Male and Female He Created Them’: Gen 1:27b in the Context of the Priestly Account of Creation,” Harvard Theological Review 74 [1981]: 146). This is certainly not because the ancient Israelites were ignorant of other races and cultures: Palestine was a crossroads of ancient civilizations. The Israelites were fully aware of Africans and Asians, people of varying ethnicities, speaking a host of languages, coming from a variety of cultures. Yet Israel does not distinguish among these races and nations, as though some are more human than others. Certainly, this text does not identify the Israelites as human, and their neighbors as something less. Instead, as George Kelsey (African American theologian and mentor to Martin Luther King, Jr.) understood, there is just ‘adam: one single human family (George D. Kelsey, Racism and the Christian Understanding of Man [New York: Scribner, 1965]).

This is a remarkable confession, rejecting every form of racism and jingoistic nationalism. Again, as Scripture sadly but faithfully bears witness, Israel was not always faithful to this insight. But as we will see throughout these Lenten reflections, it is an insight that recurs again and again—and one that the church in our day must reclaim.

Prayer: Holy God, Genesis identifies no “kinds” of people, but we have been swift to make up that lack, hastening to identify all sorts of folk as outsiders, strangers, aliens, who are not welcome in our communities. Help us to see and repent of this sin, Abba. Teach us to love whom you love, as you love, for this is our prayer in the name of your son Jesus, who “came to what was his own, and his own people did not accept him” (John 1:11), Amen.

AFTERWORD: In his theology and ethics, George D. Kelsey “pointed to the Genesis creation narrative and its assertion of a singular and common ancestry of all humanity” (Torin Alexander, “World/Creation in African American Theology,” in The Oxford Handbook of African American Theology, ed. Katie G. Cannon and Anthony B. Pinn [New York: Oxford University, 2014], 186.)