Wednesday, March 15

“So the Lord scattered them abroad from there over the face of all the earth, and they left off building the city. Therefore it was called Babel, because there the Lord confused the language of all the earth; and from there the Lord scattered them abroad over the face of all the earth” (Genesis 11:8-9).

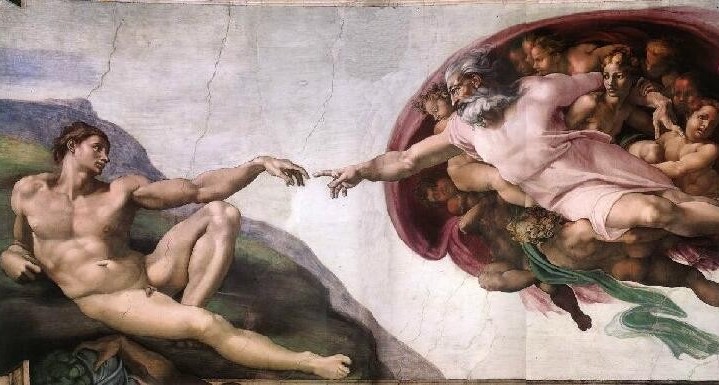

The people of Babel wanted to stay all together, and all the same. But God willed differently. The Babel story itself gives no indication of whether or not the people realized that their desires ran counter to God’s. But the old priestly traditions in Genesis state this plainly. The priestly accounts of creation and flood alike declare that humanity was to “fill the earth” (Genesis 1:28; 9:1). As the Table of Nations in Genesis 10 concretely describes, this meant not only being geographically scattered, but ethnically and culturally diverse.

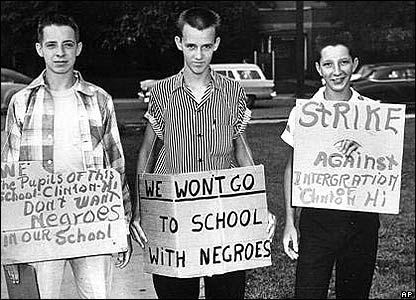

By staying together and squelching difference, the people of Babel—whether knowingly or not—were standing in the way of the diversity of expression that is God’s intent for human beings. So too our own attempts to impose homogeneity on our communities run counter to God’s will. Racial and cultural diversity is not a problem to be overcome. It is a gift of God, to be celebrated and embraced.

Prayer: Forgive us, O God, when in our longing for comfort and familiarity we stand in the way of your plan and purpose for us. Teach us to reach outside our safe enclaves and welcome all your children as our sisters and brothers. In the name of Jesus, whose reign embraces all, Amen.