Since the assassination attempt against candidate Donald Trump which left one innocent rally attender dead and wounded two others, calls for national unity have come from across the political spectrum. Unfortunately, on closer examination, many of these are really calls for uniformity: if you would just think and act like us, then our national divisions would be healed!

Since the assassination attempt against candidate Donald Trump which left one innocent rally attender dead and wounded two others, calls for national unity have come from across the political spectrum. Unfortunately, on closer examination, many of these are really calls for uniformity: if you would just think and act like us, then our national divisions would be healed!

Biblical ideas of unity, on the other hand, always involve unity in diversity. Typical is Paul’s image of the church as the body of Christ:

If the whole body were an eye, what would happen to the hearing? And if the whole body were an ear, what would happen to the sense of smell? But as it is, God has placed each one of the parts in the body just like he wanted. If all were one and the same body part, what would happen to the body? But as it is, there are many parts but one body. So the eye can’t say to the hand, “I don’t need you,” or in turn, the head can’t say to the feet, “I don’t need you” (1 Corinthians 12:17-21).

But the best indication of God’s rejection of uniformity is Genesis 11:1-9. True, traditional readings of the Tower of Babel story see it rather as a warning against unchecked ambition. By this reading, the sin of Babel is the tower, with which they sought to reach the heavens on their own. It was to halt this prideful ambition that God cursed them by confusing their languages, stopping the construction and forcing them to divide into language groups and scatter.

But as Theodore Hiebert has observed, that traditional reading misses the reason the text itself gives for their building: not so as to reach the heavens, but because “otherwise we shall be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth” (Genesis 11:4; Theodore Hiebert, “The Tower of Babel and the Origin of the World’s Cultures,” Journal of Biblical Literature 126 [2007]: 29-58). Sure enough, when God decides to act, God says nothing about the tower, or pride—or indeed, about punishment. God acts because the people are about to succeed in their goal of remaining “one people” with “one language,” so that “nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them.” Having circumvented God’s will in this, what else might they do?

This is neither a story condemning the sin of unchecked ambition, nor an account of divine punishment for that sin. It is about God stepping in to ensure difference and diversity, just as humans are about to succeed in enforcing sameness.

Why does God do this? Perhaps because, as Argentinian Methodist theologian José Míguez Bonino wrote,

God’s intention is a diverse humanity that can find its unity not in the domination of one city, one tower, or one language but in the “blessing for all the families of the earth” (Genesis 12:3)” (José Míguez Bonino, “Genesis 11:1-9: A Latin American Perspective,” in Return to Babel: Global Perspectives on the Bible, ed. Priscilla Pope-Levison and John R. Levison [Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1999], 15-16).

God loves diversity.

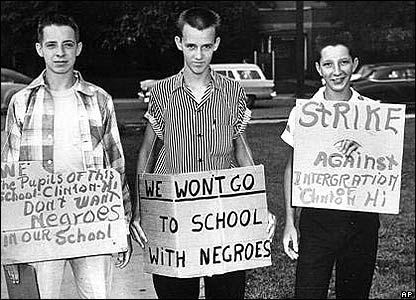

In 1956, Rev. W. A. Criswell, pastor of First Baptist Church in Dallas, Texas—at that time the largest Baptist church in the world—was invited to address the General Assembly of the South Carolina legislature on the subject of racial segregation. In his cringingly self-revealing remarks, Criswell condemned “scantling good-for-nothing fellows who are trying to upset all the things that we love as good old Southern people and good old Southern Baptists.”

Don’t force me by law, by statute, by Supreme Court decision. . . to cross over in those intimate things where I don’t want to go. . . Let me have my church. Let me have my school. Let me have my friends (Cited in Robert P. Jones, The End of White Christian America [New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016], 167).

Rev. Criswell could just as well have spoken for the First Church of Babel. The denizens of that place built their city and their tower to ensure that they would stay together in homogeneous uniformity: “otherwise we shall be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth” (Genesis 11:4).

We sometimes refer to the confusion of the world’s languages and the scattering of humanity as the “curse of Babel”—but being “scattered abroad” was exactly what God intended for humanity! The real curse of Babel is staying where we are comfortable and unchallenged, in “my church,” “my school,” with “my friends.” Babel itself, in its safe, comfortable, stultifying sameness, is the curse.

The people of Babel wanted to stay all together, and all the same. But God willed differently. The Babel story itself gives no indication of whether or not the people realized that their desires ran counter to God’s. But the old priestly traditions in Genesis state this plainly. The priestly accounts of creation and flood alike declare that humanity was to “fill the earth” (Genesis 1:28; 9:1). As the Table of Nations in Genesis 10 concretely describes, this meant not only being geographically scattered, but ethnically and culturally diverse.

By staying together and squelching difference, the people of Babel—whether knowingly or not—were standing in the way of the diversity of expression that is God’s intent for human beings. So too our own attempts to impose homogeneity on our communities run counter to God’s will.

Jacqueline Lapsley recalls being with Theodore Hiebert at a conference of Reformed theologians and Bible scholars in South Africa. There, he advanced the reading of the tower of Babel story we have advocated in this post: that this story demonstrates God’s love of cultural diversity. But when they heard this, South African scholars present were horrified! It seems that this very text, and a reading very like Hiebert’s, had been “one of the central biblical foundations for apartheid. On the pro-apartheid reading, Gen 11 teaches that God does not want different cultural and linguistic groups to live together” (Jacqueline Lapsley, “‘Am I Able to Say Just Anything?’: Learning Faithful Exegesis from Balaam,” Interpretation 60 [2006]: 23).

Does this invalidate Hiebert’s reading of this passage? I don’t believe it does—although it certainly points up a problem with how we do biblical interpretation (also called “exegesis,” from Greek words meaning “draw out”)!

Lapsley warns against readings of Scripture that “serve our own selfish interests,” or that fail to consider “God’s larger story.” In the end, she proposes,

Exegesis requires certain learned skills—how to attend to the historical, social, and literary facets of the text—but it also requires a disciplined imagination and something even more important—faith that God’s word has power to speak to and for us, and especially faith that it speaks to and for those who are far removed from the prosperity we enjoy (Lapsley, “Learning Faithful Exegesis,” 30).

Reading Scripture prayerfully, guided by God’s Spirit, with disciplined imaginations, we can make wise choices about how to apply the Bible to our own contexts. When we do this, we can readily see that affirming the God-given goodness of our differences leads, not to apartheid, but to learning to live together in love.

The account of Pentecost in Acts 2 clearly draws on the Babel story. Jesus’ followers were waiting together in Jerusalem as he had commanded them, praying in an upper room, when “All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other languages, as the Spirit gave them ability” (Acts 2:4). Boiling out of that room and into the streets, they met Jewish pilgrims from all over the Roman world, who had come to Jerusalem for Pentecost. These visitors discovered, to their astonishment, that they could understand Jesus’ Galilean followers perfectly: “‘in our own languages we hear them speaking about God’s deeds of power’” (Acts 2:11).

Please notice that this passage does not say that the people all started speaking the same language—that their cultural and ethnic distinctiveness was denied or undone. The Spirit does not return them to “one language and the same words” (Gen 11:1). Instead, each group hears God’s praise in its own language.

In Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED Talk, “The Danger of a Single Story,” she relates her first encounter with her first college roommate, in America:

She asked where I had learned to speak English so well, and was confused when I said that Nigeria happened to have English as its official language. She asked if she could listen to what she called my ‘tribal music,’ and was consequently very disappointed when I produced my tape of Mariah Carey. . . . My roommate had a single story of Africa: a single story of catastrophe. In this single story, there was no possibility of Africans being similar to her in any way, no possibility of feelings more complex than pity, no possibility of a connection as human equals.

We should not be surprised that the members of the Pentecost crowd all hear the Gospel in their own languages. The entire Bible models for us how to escape the danger of the single story. Scripture rarely gives us a single story about anything! At the beginning of our Bible, we find two different accounts of the creation of the world (one in Genesis 1:1—2:4a, and another in Genesis 2:4b-25). Our New Testament opens with four gospels, presenting four quite different accounts of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection. Scripture itself calls for us to listen with open ears and open hearts for the truth told, not as a single story, but as a chorus of voices. Sometimes those voices are in harmony, sometimes they are in dissonance, but always they are lifted in praise to the God who remembers all our stories, the comedies and tragedies alike, and catches them up together in love, forgiveness, and grace. Racial, cultural, and gender diversity is not a problem to be overcome, but a gift of God, to be celebrated and embraced.