In Genesis 1:1–2:4a, creation is imagined as taking place in the span of a single week, with the seventh day, the Sabbath, as a day of rest. Humans are created at the end of the sixth day, making us the last creatures that God makes. In this first creation account, we are the climax of creation.

The text sets the creation of human beings apart from the rest of creation in several ways. First, Gen 1:26 says, “Then God said, “Let us make humanity.” What do we do with the plural here? To whom is God speaking? Christian readers have sometimes found in this verse a reflection of the Trinity, so that the Father here addresses the Son and the Holy Spirit.

But the ancient priests of Israel would not have thought about God in those terms. Parallels with other stories of creation in the ancient Near East reveal that the best way to understand this text in its historical context is as referring to a council of heavenly beings.

In the Enuma elish, creation is an act of committee. The gods elected Marduk as their king and champion, to defeat the chaos monster Tiamat. But once she was dead, the other gods joined with Marduk in the creation of the world.

Ea, the god of wisdom, counseled Marduk on a special aspect of this work: the creation of people. According to the Babylonian creation story, “savage-man” was fashioned as a slave race, to serve the gods.

While the view of human being and of God is very different in Genesis 1 than in the Enuma elish, the simplest way to understand the plural in Genesis 1:26 is that here too the Creator is addressing a council of heavenly beings. Still, faith in the incomparable God once again causes Israel to take a different stance than its neighbors. In Genesis, the council is decidedly in the background: God neither asks the council’s permission, nor seeks its aid. Indeed, God has not said “let us” before; only the creation of human being involves the council at all. Perhaps the council is mentioned here primarily to set human beings apart from the rest of creation.

Rather than the traditional KJV reading, “Let us make man,” the CEB has ““Let us make humanity” (Gen 1:26). This is not political correctness: it is a matter of accurate translation. In Hebrew, the word for “man” is ish. But that is not the word that is used here. In Genesis 1:26, God decides to create ‘adam, which means “humanity.”

Human being, already distinguished by the mention of the divine council, is further distinguished by something not mentioned. There are “kinds” of everything else in creation: plants, birds, fish, and animals (Gen 1:11-12, 21, 24-25). However, there are no “kinds” of people.

This is not because the ancient Israelites were ignorant of other races and cultures: Palestine was a crossroads of ancient civilizations. The Israelites were fully aware of Africans and Asians, people of varying ethnicities, speaking a host of languages. Yet Israel does not distinguish among these races and nations, as though some are more human than others. Instead, there is just ‘adam: one single human family. It is a remarkable confession, rejecting every form of racism and jingoistic nationalism.

It is particularly important that we translate ‘adam correctly, because Genesis 1:27 goes on very plainly to state:

God created humanity in God’s own image,

in the divine image God created them,

male and female God created them.

Masculinity and femininity, maleness and femaleness, are each reflections of God-likeness in this verse. There is no hierarchy of the sexes here; no basis for placing women under men.

To be sure Israel’s traditions were not always equal to this insight. Yet here it is, at the very beginning of the Bible! Sexism, like racism, is denied any place in the priestly view of God’s ordered world. Further, to say that maleness and femaleness are both representations of “God-likeness” is also to say that God is neither male nor female—or more accurately, that both masculinity and femininity reflect aspects of God. While the dominant images of God in the male-centered culture of ancient Israel were masculine, one of the dominant features of Israel’s theology from early on was an absolute refusal to make an image of God: the point being that no image can adequately express God’s being. Further, there are texts which depict God in feminine terms–specifically, as midwife (Ps 22:9-10) and as mother (Hos 11:1-4). The God of Scripture is not a big man in the sky!

Returning to Genesis 1:26, the most distinctive aspect of human being in this account is our God-likeness:

Then God said, “Let us make humanity in our image to resemble us” (Gen 1:26).

The more familiar language of the King James reads, “in our image, after our likeness.” What might it mean that we are made in the likeness (Hebrew demut) and image (Hebrew tselem) of God?

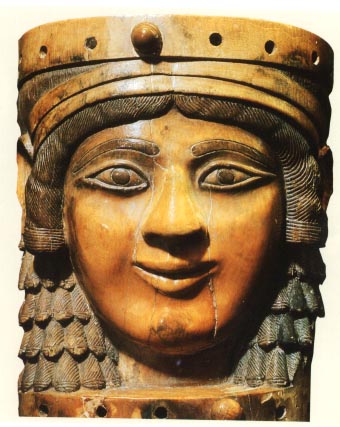

Insight may come from a mid-ninth century B. C. memorial inscription found on a statue at Tell Fekheriyeh, in which these words also appear.

This old Aramaic text describes the statue as the “likeness” and “image” of Hadad-yis’i, governor of Guzan in the Assyrian empire. This could simply mean that the statue looks like him (as the CEB “to resemble us” in Gen 1:26 suggests). But since this is a funerary inscription, it more likely means that this image represents Hadad-yis’i: it calls the governor to mind, even though he is no longer physically present.

The Hebrew words demut, (“likeness”) and tselem (“image, statue”) found in Genesis 1 could also relate to the idea of representation. Just as his memorial statue preserves the memory of Hadad-yis’i, calling him to our minds even today, millennia after his death, so looking into the face of another human being calls God to mind.

By saying that humans bear God’s image, the priests are saying something about God, as well as something about humanity. Our passage understands God in personal terms. This is another a remarkable step out of the mythic background of the ancient Near East. The gods of the nations were embodiments of natural forces or powers. Baal was the thunderstorm,

Asherah was motherhood,

and Ishtar was raw sensuality.

But in Genesis 1:26, the priests of Israel say that God’s likeness is seen in humanity, and implicitly (since that likeness is shown in “male and female”), in relationships.

But in Genesis 1:26, the priests of Israel say that God’s likeness is seen in humanity, and implicitly (since that likeness is shown in “male and female”), in relationships.

The rest of the Bible, it could be said, pursues the question, “How can we be in relationship with God?” Right at the start, we have a clue in our very humanity. Our own longing for relationship, for connection with one another, tells us something of God’s love for us.

Genesis 1:26 goes on to define what being created in the image of God means in greater detail:

Then God said, “Let us make humanity in our image to resemble us so that they may take charge of the fish of the sea, the birds in the sky, the livestock, all the earth, and all the crawling things on earth.”

Presumably, the image and likeness of God in human being is related to “taking charge” (Hebrew radah) over the rest of creation. In sharp contrast to the Enuma elish, in which humans are a slave race, in Genesis 1 we are honored as the lords and ladies of creation! Under God’s divine lordship as the ruler of the cosmos, we are appointed as regents, governing in God’s stead. Humans stand in for God in material reality, concretely representing God’s rule.

Our passage goes on to affirm,

God blessed them and said to them, “Be fertile and multiply; fill the earth and master it. Take charge of the fish of the sea, the birds in the sky, and everything crawling on the ground.” (Gen 1:28).

Unfortunately, in the history of our faith, believers often have understood mastering the earth to mean abusing the earth: we are free to use the world, and even to use it up, as we see fit.

But it is apparent that this is not the intention of Genesis 1. Consider God’s continual assessment of the world God is making: “God saw how good it was” (Gen 1:4, 10, 12, 18, 21, 25). Finally, when the work of creation was done, “God saw everything he had made: it was supremely good.” (Gen 1:31).

The goodness of creation does not depend on its utility for human beings: God calls the world good before we show up at the end of Day Six! The creation is good because God calls it good, quite apart from whether or not we can use it. As in Psalm 104, where God’s presence is affirmed in all the world, even down in the depths with Leviathan where no human can live, Genesis 1:1—2:4a affirms God’s valuation of the world in and for itself. If we exercise our dominion properly, we too will recognize the wonder, beauty and inherent goodness of the world that God has made, and exercise our responsibility as proper stewards of the earth.

The absence of conflict and the emphasis upon order in Genesis 1 leads to a rather intriguing conclusion. In Genesis 1:29-30, God says,

“I now give to you [that is, humanity] the plants on the earth that yield seeds and all the trees whose fruit produces its seeds within it. These will be your food. To all wildlife, to all the birds in the sky, and to everything crawling on the ground—to everything that breathes—I give all the green grasses for food.”

According to this text, God’s original will was for all creatures, humans and animals alike, to be vegetarian! Permission to eat meat is not given, in the priests’ understanding, until after the great flood (see Gen 9:1-7). As the priests imagine it, God’s dream is that the world be, like Hicks’ “Peaceable Kingdom,” a place of peace and beauty, where nothing has to die for something else to live.

This harmonious order extends past the actual work of creation. In Genesis 2:1-2, we read,

Thus the heavens and the earth were finished, and all their multitude. And on the seventh day God finished the work that God had done, and God rested on the seventh day from all the work that God had done. (NRSV)

What a marvelous image! God rests, trusting the world that God has made enough to let it go. God not only rests, but sanctifies the day of rest: “God blessed the seventh day and made it holy, because on it God rested from all the work of creation.” (Gen 2:3). Through Sabbath rest, human beings are given another way to be like God.

As we have seen, the six days of creation stand in parallel to one another: the light on day one to the lights on day four; the sky dome separating the waters on day two to the birds in the air and the fish in the water on day five; the creation of dry land and plants on day three to the creation of animals and humans, to live on the land and eat the plants, on day six. The seventh day alone stands apart, without parallel, as the climax of creation. In this priestly depiction of reality, Sabbath is part of the structure of the universe. The sacredness of the seventh day is woven into the warp and woof of creation.

The structure of reality in Genesis 1:1—2:4a is very like architecture, with the six days arranged in parallel, like the columns of a building:

Day 1: Light Day 4: Lights

Day 2: Sky dome Day 5: Birds and fish

Day 3: Dry land Day 6: Land animals

Plants Humanity

Day 7: Sabbath

In ancient Palestine and Syria, temples were built on a long room design: an entrance with a vestibule opened into a long main room with pillars. At the back of the temple would often be a separate room, the Most Holy Place. In Phoenician and Canaanite temples, that room held the image of the god. In the temple of Israel in Jerusalem, the inner room held God’s footstool, the Ark of the Covenant, above which God was invisibly enthroned.

The Most Holy Place, where the Ark was kept, became the place of the LORD’s special, particular presence. If the six days of creation correspond to the main room, then Sabbath, the day apart without parallel, would be the Most Holy Place, where the Divine can be encountered. Keep in mind, though, that in the priestly worldview God’s image is found in human beings. It is when we look in the eyes of another human being that we come closest to understanding who God is.

In Genesis 1:1—2:4a, the priests describe the world as a carefully and intricately ordered place: a temple built in time. The symmetry and elegance of this world invite us to contemplate the wisdom and majesty of its creator, who imposes order upon chaos. Does the world make sense? The priests of ancient Israel affirm that it does. Our God gives meaning to our world, and to our lives.