This Sunday marks the end of this Christian year; next Sunday, with Advent, a new year will begin. The last Sunday of the Christian year is called the Reign of Christ, or the feast of Christ the King. Appropriately, the Gospel for this Sunday, John 18:33-37, relates Jesus’ trial before Pilate: has Jesus claimed to be a king, in opposition to Caesar?

Pilate went back into the palace. He summoned Jesus and asked, “Are you the king of the Jews?”

Jesus answered, “Do you say this on your own or have others spoken to you about me?”

Pilate responded, “I’m not a Jew, am I? Your nation and its chief priests handed you over to me. What have you done?”

Jesus replied, “My kingdom doesn’t originate from this world. If it did, my guards would fight so that I wouldn’t have been arrested by the Jewish leaders. My kingdom isn’t from here.”

“So you are a king?” Pilate said.

Jesus answered, “You say that I am a king. I was born and came into the world for this reason: to testify to the truth. Whoever accepts the truth listens to my voice.”

We need to be clear on two points. First, Jesus was a political prisoner, executed by the Roman state on the charge of insurrection. When Christians reflect on the cross, we tend to forget, or perhaps even to ignore, this obvious truth. Rome didn’t crucify thieves, or bandits, or rapists, or even murderers. It crucified slaves, and those who rebelled against Roman authority.

The words Pilate posted above Jesus’ head on the cross were not a title, but an accusation–the accusation that brought him to the cross: “Jesus the Nazarene, the king of the Jews.”

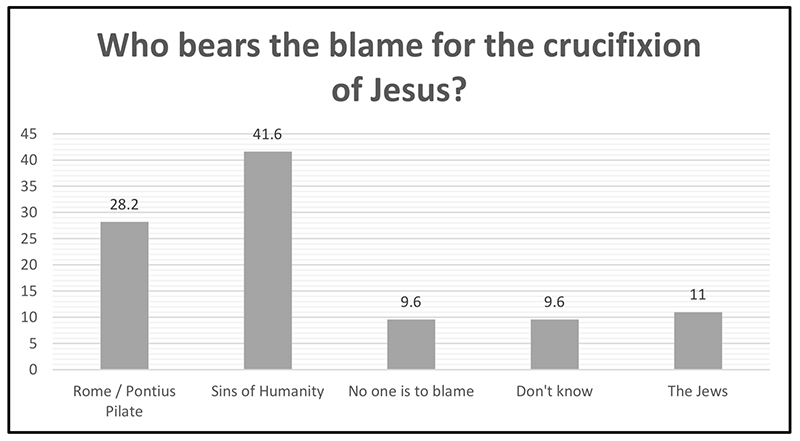

Thankfully, a survey of Roman Catholic Christians conducted by St. Joseph’s Institute for Jewish-Catholic Relations in July 2022 with SurveyUSA determined that “Catholics were significantly more likely to affirm Catholic teaching regarding the crucifixion of Jesus Christ.”

Nearly 70% of respondents blamed “the sins of humanity” (41.6%) or Roman soldiers and Pontius Pilate (28.2%).

Who killed Jesus? If our question is historical, then as 28.2% of those surveyed thankfully realized, Jesus was condemned and executed by Roman authority. If our question is theological, as 41.6% of those surveyed understood it, then we killed Jesus: Jesus died for your sins and mine. In her powerful devotional book God Is No Fool (Nashville: Abingdon, 1969), Lois A. Cheney writes:

Would we crucify Jesus today? It’s not a rhetorical question for the mind to play with.

I believe,

We are born with a body, a mind, a soul, and a handful of nails.

I believe,

When a man dies, no one has ever found any nails left,

clutched in his hand

or stuffed in his pockets (Cheney, 40-41).

The scholars at St. Joseph’s “seemed unsettled that roughly 30% of U.S. Catholics didn’t know (9.6%)” who was accountable for the death of Jesus, “thought no one is to blame (9.6%) or openly blamed Jewish people (11%).”

The Jews did not kill Jesus–Rome did. But given the sad resurgence of antisemitism in contemporary American life, I wonder what a similar survey of Protestant Christians would reveal?

The second point on which we must be very clear is that Jesus firmly rejects earthly, political kingship: “My kingdom doesn’t originate from this world. If it did, my guards would fight so that I wouldn’t have been arrested by the Jewish leaders. My kingdom isn’t from here” (John 8:36).

This was not the first time that Jesus rejected an earthly kingdom. At the very beginning of his ministry, when Jesus was tested in the wilderness:

This was not the first time that Jesus rejected an earthly kingdom. At the very beginning of his ministry, when Jesus was tested in the wilderness:

Then the devil brought him to a very high mountain and showed him all the kingdoms of the world and their glory. He said, “I’ll give you all these if you bow down and worship me.”

Jesus responded, “Go away, Satan, because it’s written, You will worship the Lord your God and serve only him” [see Deuteronomy 6:13]. The devil left him, and angels came and took care of him (Matthew 4:8-11).

This point is vital, friends, as some American Christians seem to have the idea that it is their task to restore Christian political power, and indeed to impose Christian rule. President-elect Donald Trump promised in his campaign to “champion his followers’ brand of Christianity across American life and government. . . his support for ‘my beautiful Christians,’ as he calls them, leans heavily into their fears about losing power in a secularizing and pluralist country.”

Accordingly, Mr. Trump “is promising to elevate not only [conservative Christian] policy priorities but also their ideological influence. He says he will affirm that God made only two genders, male and female. He will create a federal task force to fight anti-Christian bias. And he will give enhanced access to conservative Christian leaders. . . ‘It will be directly into the Oval Office — and me,’ Mr. Trump told pastors in Georgia. ‘We have to save religion in this country.’”

We need to call this so-called “Christian nationalism” what it is, friends: it in fact is not Christian at all, but a heresy. Amanda Tyler, the executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty (BJC), identifies the tenets of this American heresy:

Grace and peace to you from the one who is and was and is coming, and from the seven spirits that are before God’s throne,and from Jesus Christ—the faithful witness, the firstborn from among the dead, and the ruler of the kings of the earth. To the one who loves us and freed us from our sins by his blood,who made us a kingdom, priests to his God and Father—to him be glory and power forever and always. Amen

Look, he is coming with the clouds! Every eye will see him, including those who pierced him, and all the tribes of the earth will mourn because of him. This is so. Amen.

John’s reference to Jesus as the “pierced” one alludes to an enigmatic text from Zechariah:

And I will pour out a spirit of compassion and supplication on the house of David and the inhabitants of Jerusalem, so that, when they look on the one whom they have pierced, they shall mourn for him, as one mourns for an only child, and weep bitterly over him, as one weeps over a firstborn (Zech 12:10, NRSVue).

But who is this pierced one? Our Hebrew Bible reads ‘elay ‘eth ‘asher-daqaru: “to me whom they have pierced.” The third person forms used later in the verse (“mourn for him . . . weep over him”) suggest that perhaps ‘elay should read ‘elaw (“to him”)—a common scribal error. Accordingly, the NRSVue has “the one whom they have pierced” (although noting the Hebrew reading in a footnote). The Greek text of John 19:37, which also quotes this verse, reads hopsontai eis hon exekentesan, “they shall look at him whom they have pierced,” which seems to be the form of the saying assumed by most early Christian writers.

However, the Greek Septuagint keeps the first person reference in Zechariah 12:10, translating the phrase as epiblepsontai pros me anth’ on katorchesanto (“they shall look to me because they mocked”[?]; the Greek texts of Aquila, Symmachus, and Theodotian have exekentesan, “they pierced,” instead of katorchesanto, “they mocked”). The early Christian teacher Theodoret of Cyrus accordingly read, “They will look on me, on the one they have pierced” (Commentary on the Twelve Prophets). The Latin Vulgate also uses the first person (aspicient ad me quem confixerunt; “they shall look upon me whom they have pierced”), as does the old King James Version: “they shall look upon me whom they have pierced.”

If the Hebrew text of Zechariah 12:10 is correct here, as seems likely from the textual evidence, the simplest and best reading is, “when they look on me whom they have pierced.” Incredible as it seems, this passage refers to an assault by Jerusalem’s leaders upon God. The one “whom they have pierced” is the LORD.

God responds to this rejection, this wounding, with an outpouring of God’s Spirit (as in Joel 2:28-29 [in Hebrew, 3:1-2]). But here, God pours out “a spirit of compassion and supplication on the house of David and the inhabitants of Jerusalem” (12:10). This spirit sufficiently softens their hearts so that “when they look on the one whom they have pierced, they shall mourn for him, as one mourns for an only child, and weep bitterly over him, as one weeps over a firstborn.”

Returning to Sunday’s epistle reading, Revelation 1:7 also alludes to Zechariah 12:12: “The land will mourn, each of the clans by itself.” But here, John follows the Septuagint reading kai kopsetai he ge kata phulas (“the earth shall mourn by tribe”). So John declares that every tribe on earth will see the exalted, returning Christ–and everyone will be brought by this revelation to mourning and repentance.

What kind of king is Jesus? He is not a cruel despot, like Pilate or Caesar–or indeed, like any of the kings of the earth over whom he reigns. He is the pierced one, who knows our suffering from the inside, who by his blood has freed us from the power of our own sin. He comes, not to avenge, but to bring us all to a full recognition of our own violence and hatred, that we may move through confession to healing grief and repentance.