Recently, I was captivated by a quote from A. J. Jacobs, the author of The Year of Living Biblically (2007), regarding his most recent book, The Puzzler (2022):

I’m an advocate of what I call the Puzzle Mindset. Instead of seeing the world as a series of hard-to-win battles, I try to view it as a puzzle–to see the world through the eyes of an engineer, not a warrior. Even using the word puzzle can help. When I hear about the climate crisis, I want to curl up in a fetal position. But if I think about the climate puzzle, I feel motivated to find solutions.

As a Bible Guy, I tend to think biblically–in terms of texts and images from Scripture. So Jacobs’ challenge “to see the world through the eyes of an engineer, not a warrior” got me thinking about martial metaphors in Scripture. The earliest passages in the Bible celebrate God as the Divine Warrior: the Song of Deborah in Judges 5; the song of David in 2 Samuel 22//Psalm 18; the psalm in Habakkuk 3; Psalm 68; and in particular, the oldest passage in Scripture, Exodus 15:1-18, the Song of the Sea.

I will sing to the Lord, for an overflowing victory!

Horse and rider he threw into the sea!

The Lord is a warrior;

the Lord is his name.

Pharaoh’s chariots and his army he hurled into the sea;

his elite captains were sunk in the Reed Sea.

The deep sea covered them;

they sank into the deep waters like a stone (Exod 15:1, 3-5).

Unfortunately, because we so readily think of our world as “a series of hard-to-win battles,” and so of life as combat, we are likely to forget that this ancient biblical metaphor is a metaphor, and to embrace it uncritically. A personal example of this tendency takes me back eight years, to the time soon after my ankle replacement surgery.

I remember waking up on one morning to the realization that my leg was itching under the cast, where I couldn’t reach. It was driving me crazy. I twisted my leg inside the cast, got up, stomped around on the walker–and then realized that I would be trapped in that cast for another three weeks.

I sat in my recliner with the offending limb stuck up in the air, trying to read, trying to pray–trying desperately to think about something, anything, other than my leg–to no avail. I imagined that ants were crawling around on my leg under the cast. I began to have trouble breathing. My heart was racing. I was disoriented. I thought, “I am having a panic attack. This must be what a panic attack feels like.”

Then I thought about my son Sean. Sean has wrestled since childhood with Tourette Syndrome and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Along the way, he has learned not only to cope, but to thrive. So I asked him if he could teach me how to fight my obsession with my leg’s discomfort.

Sean’s answer astonished me. He said he had learned that you can’t fight obsessive thoughts: “They just come.” What you can do is rob those thoughts of the emotions and anxiety associated with them. To do that, Sean taught me, you first relax your body and your mind. Then, you let the forbidden thought come: you deliberately think about what you do not want to think about. As you do so, you keep breathing slowly; you deliberately relax, and so replace the anxiety with calm. Sean suggested that I think, “My leg is uncomfortable, but that really doesn’t matter!”

That night, when my leg itched, I didn’t try to fight it. I breathed slowly, in and out, praying the Jesus Prayer in time with my breathing: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, be merciful to me, a sinner.” I thanked God for my healing. I thought about the hundreds of other people who had had this same surgery, and had come through this period of recovery just fine. I told myself, “My leg is uncomfortable, but that really doesn’t matter.” And I fell asleep–the most restful sleep I had had since coming home from the hospital.

Over the next three weeks, I continued to practice my prayer and meditation, and bit by bit, my leg stopped bothering me. It didn’t become magically more comfortable, or less prone to itching, but I stopped worrying about it. I “won” the fight when I stopped fighting!

Please do not misunderstand me. I do not question society’s need for warriors. Undoubtedly, there are times when resistance to political and social evil requires a militant response: as is the case today in Ukraine. But under the dominant influence of the martial metaphor, resistance to any evil becomes a war: the War on Drugs, the War on Crime, the War on Terror. Theologian Walter Wink called this seductive notion the “myth of redemptive violence”:

Violence is the ethos of our times. It is the spirituality of the modern world. It has been afforded the status of a religion, demanding from its devotees absolute obedience to death. . . Violence is so successful as a myth precisely because it does not appear mythic in the least. Violence simply appears to be the nature of things. It is what works. It is inevitable, the last and, often, the first resort in conflicts (Walter Wink, Engaging the Powers: Discernment and Resistance in a World of Domination [Minneapolis: Fortress, 1992], 23).

In a seventeen-minute video appeal to his fellow Evangelicals, Phil Vischer, creator of the wonderful Veggie Tales series, briefly summarizes the horrific history of race in America–faulting, in particular, the martial metaphor. The War on Crime and the War on Drugs, he argues, led us to militarize our police, and to criminalize and incarcerate an entire generation of Black and Brown Americans.

Tara O’Neill Hayes, the Director of Human Welfare Policy at the American Action Forum, has the sobering statistics:

There are currently an estimated 2.2 million people incarcerated in the United States. The incarceration rate is now more than 4.3 times what it was nearly 50 years ago. This increase has led to the United States having the highest incarceration rate of any country in the world, 37 percent greater than that of Cuba and 69 percent greater than Russia. This high incarceration rate is not because crime has increased; in fact, crime rates have declined since the 1990s. Rather, the arrest rate increased dramatically, while sentences—particularly for drug crimes—have gotten longer. These policy changes have disproportionately affected low-income and minority populations, who now make up roughly three-fifths and two-thirds of the prison population, respectively.

President Biden’s recent clemency actions, pardoning three people and commuting the sentences of 75, were a small start on responding to this injustice: “White House officials say the president thinks too many people — many of them Black and brown — are serving unduly long sentences for drug crimes.”

In the wake of the very public, brutal murder of African American George Floyd by a white police officer, worldwide protests called for justice and reform–including calls, specifically, to “Defund the Police.” But a far better call would be to ditch the martial metaphor, and demilitarize the police–as they did in Camden, New Jersey.

In 2013, Camden had one of the highest murder rates in the country. In response to that sobering statistic, the city “dismantled the entire police department, starting a community policing approach.”

The department un-hired, then hired back most veteran officers and then 150 new officers — 50% of officers are now minorities. . . . The new force has more officers on the streets out of their cars, having conversations and mostly listening. They go through de-escalation training. . . they are trained to use their words, and guns are a last resort.

Retired Police Chief Scott Thompson, who helped start the new program, describes the difference like this: “from day one. . . our officers would be guardians and not warriors.” It worked. After the police in Camden ditched the martial metaphor, choosing (and training themselves) to be “guardians and not warriors,” shootings and murders went down by 50% in two years. Metaphors matter!

So, what about those biblical texts depicting God as a warrior? It is important that we hear these ancient songs, not from the perspective of a strong, secure, and self-confident Israel, but of an Israel in its infancy—a people fragile and vulnerable, who had until very recently been no people, hanging onto survival by their fingernails. Otherwise, we may use the image of God as a warrior standing against Israel’s oppressors to justify our own violence.

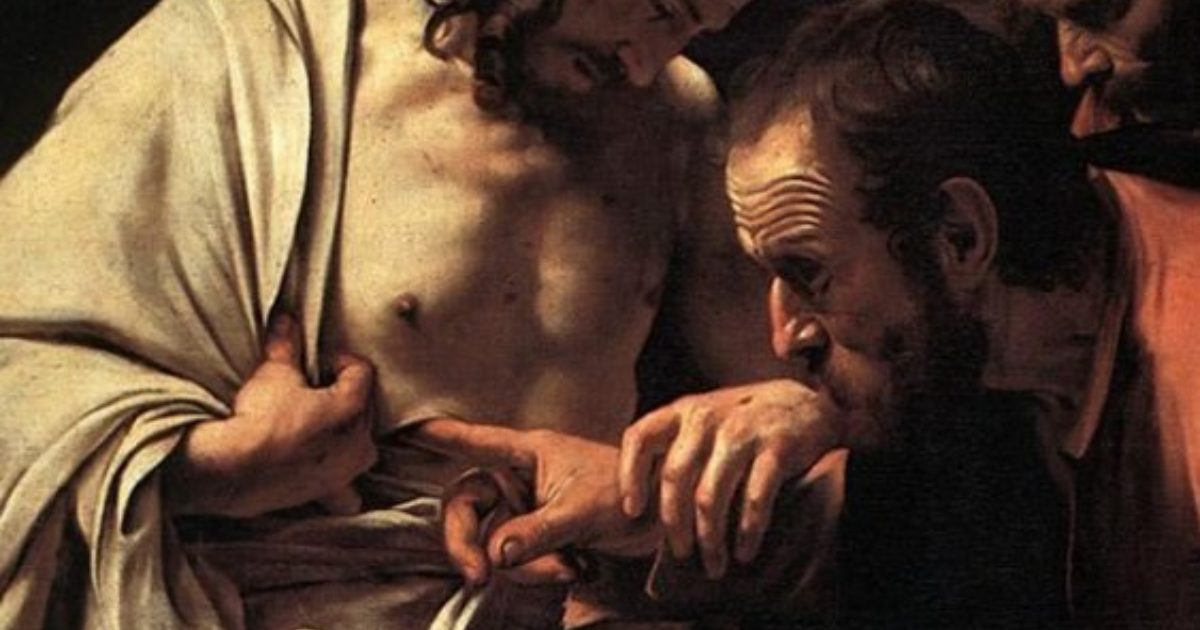

![Title: Prophet Miriam [Click for larger image view]](http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/cdri/jpeg/miriam33172410852_bcf5c473db_k.jpg)

Certainly Jewish tradition did not read the Song of the Sea as a call to arms! According to the Talmud (the authoritative collection of the teachings of the rabbis), when the Israelites began to celebrate the defeat of the Egyptians, God asked, “How can you sing as the works of my hand are drowning in the sea?” (b. Megillah 10b).

Without doubt, the imagery of warfare and struggle is part of the biblical witness. But Scripture also, in many places, subverts the martial metaphor, transforming it unexpectedly into imagery of peace.

Following the flood in Genesis, the LORD declares, “I have placed my bow [Hebrew qeshet] in the clouds; it will be the symbol of the covenant between me and the earth” (Gen 9:13). Elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible, qeshet refers to a weapon, whether in the hands of a hunter (for example, Genesis 27:3) or a warrior (for example, Zechariah 9:10). The rainbow is the LORD’s war bow (Habakkuk 3:9; Psalm 18:14), which God now sets aside, placing it in the clouds.

Remember, God had just finished destroying the world with a flood! Now, as life begins again on the renewed earth, the unavoidable question for the reader has got to be, what if this happens again? God promises that it never will:

I will set up my covenant with you so that never again will all life be cut off by floodwaters. There will never again be a flood to destroy the earth (Gen 9:11).

To underscore and seal that promise, God disarms Godself.

This is far from the only Bible passage subverting the martial metaphor! Not too long ago, on Palm Sunday, we recalled Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem (Matt 11:16-19, 25-30). In their accounts, both Matthew and John (Matt 21:5 and John 12:15) quote Zechariah 9:9 :

Rejoice greatly, Daughter Zion.

Sing aloud, Daughter Jerusalem.

Look, your king will come to you.

He is righteous and victorious.

He is humble and riding on an ass,

on a colt, the offspring of a donkey.

By riding an ass rather than a war horse or chariot, the king in Zechariah’s passage shows humility, and declares that he comes in peace. But there was a long tradition of kingly processions involving the king riding an ass (Carol and Eric Meyers, Zechariah 9-14; AB 25c [Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1993], 129). Why should this one be any different than all those others? Zechariah declares that this time, it is more than theater! The LORD’s Messiah truly is humble, and not only comes in peace, but comes to bring peace:

He will cut off the chariot from Ephraim

and the warhorse from Jerusalem.

The bow used in battle will be cut off;

he will speak peace to the nations.

His rule will stretch from sea to sea,

and from the river to the ends of the earth (Zech 9:10).

By entering Jerusalem in this way, Jesus declares what sort of Messiah he intends to be.

So, what about Revelation, where a blood-soaked Jesus returns to earth at the head of a heavenly army (Rev 19:11-16)? Doesn’t this vindicate the martial metaphor? Of course, that may be just fine with us! In the end, God is finally going to trot out the big guns, and act in a way we can understand.

If we read the book of Revelation closely, however, we are in for a surprise. The familiar biblical imagery of divine warfare (see especially Isa 63:1-3 for the blood-soaked garments and the winepress of divine wrath) is transformed when we realize that the robes of the rider on the white horse are already red with blood as he descends from heaven–so the blood cannot be from his slaughtered enemies! Indeed, the only weapon he bears is his word: the sword which comes from his mouth (Rev 19:15; see also Rev 1:16; 2:16; Heb 4:12; Eph 6:17), as is appropriate for the one called The Word of God (Rev 19:13). Whose blood, then, stains his robes? It must be his own.

In Revelation 5, John finds himself in the heavenly throne room. In God’s hand is a scroll, sealed with seven seals. John desperately wants to know what secrets the scroll contains,

But no one in heaven or on earth or under the earth could open the scroll or look inside it. So I began to weep and weep, because no one was found worthy to open the scroll or to look inside it. Then one of the elders said to me, “Don’t weep. Look! The Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, has emerged victorious so that he can open the scroll and its seven seals” (Rev 5:3-5).

John turns, fully expecting to see a Lion. But instead,

I saw a Lamb, standing as if it had been slain. It had seven horns and seven eyes, which are God’s seven spirits, sent out into the whole earth. He came forward and took the scroll from the right hand of the one seated on the throne (Rev 5:6-7).

Anything further removed from the lion John had expected to see is difficult to imagine. The lion is regal, the lamb is ordinary. The lion is powerful, the lamb is powerless. The lion is a predator, the lamb is prey. Further, it is a slaughtered lamb, which emphasizes even more its absolute powerlessness, as well as calling up another set of images associated with the lamb: the lamb as sacrifice.

Yet the lamb, although bearing the marks of slaughter, is standing–and so obviously alive, not dead! Clearly, as John the Baptist had declared in John 1:36, Jesus is the Lamb of God. In the remainder of Revelation, Jesus is never again called a Lion; but he is called the Lamb 30 times (e.g., Rev 5:12-13; 7:9-10; 12:11; 17:14; 21:22-23),

We often say that God is love (1 John 4:7-8), which surely means, if it means anything at all, that love is the strongest power in the universe: stronger than violence or coercion or control. So we should not find at all strange the marvelous assertion at the close of Scripture that the kingly power of the Lion is now invested, and manifested, in the suffering, sacrificial love of the Lamb. God, in the end, has no need of the martial metaphor. Perhaps we too should give it a rest.