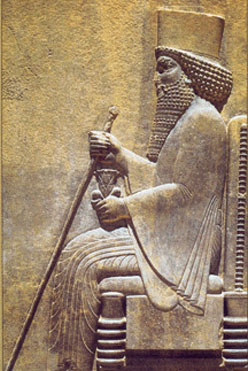

Tomorrow is Mother’s Day. For me, it is a day of joyous celebration–an opportunity to honor my own mother, Mary, for the love and blessing she has poured into my life (that’s my father Bernard on the right),

as well as my wife Wendy, mother to our three wonderful sons. Thank you, thank you, thank you–I do not know who I would be today without your love and wisdom.

But sadly, Scripture is not kind to women. To take an example particularly relevant to Mother’s Day, childbirth was regarded by the priests as a defiling act, for mother and child alike (see Leviticus 12:2-8). This is not surprising: in the priests’ world view, the life of any being was contained in the blood, so that blood belonged exclusively to God. Childbirth being a bloody process, it is little wonder that the priests regarded it as defiling. Still, the period of uncleanness is not the same with every birth, but depends upon the sex of the child: 7 days of impurity for a male child, 2 weeks of uncleanness if the baby is female!

Broadly speaking, in the patriarchal (that is, male-centered) societies out of which both our Old and New Testaments emerged, a woman was regarded as the property of a man: first her father, later her husband. In the priestly version of the Ten Commandments, Exodus 20:17 states, “Do not desire your neighbor’s house. Do not desire and try to take your neighbor’s wife, male or female servant, ox, donkey, or anything else that belongs to your neighbor.” Here, the wife, like the household servants, domestic animals, and everything else included in a man’s “house,” is regarded as property.

In the New Testament, then, it is no surprise to find passages restricting women’s role in the church. 1 Timothy 2:8-15 denies women the right to preach or lead, an argument made on the basis of the creation story: “Adam wasn’t deceived, but rather his wife became the one who stepped over the line because she was completely deceived” (1 Tim 2:14; a rather biased reading of Genesis 3, where the man and the woman alike are held accountable).

Still, this is just what we would expect to find in a text that comes, as the Bible does, out of a patriarchal culture. In biblical studies, what we do not find can prove as interesting and significant as what we do; surprises and exceptions take on a particular significance.

First of all, let’s consider the very beginning of the Bible. While the traditional reading of Genesis 1:26 has God say, “Let us make man” (see the King James Version), the Common English Bible has “Let us make humanity” (Gen 1:26). This is not, as some might think, political correctness. It is a matter of accurate translation. In Hebrew, the word for “man” is ‘ish. But the word used here is ‘adam, which means “humanity.” Human being is set apart from everything else in creation by something not mentioned. There are “kinds” of plants, birds, fish, and animals (see Genesis 1:11-12, 21, 24-25). However, there are no “kinds” of people. This is not because the ancient Israelites were ignorant of other races and cultures: Palestine was a crossroads of ancient civilizations, African and Asian; Jews regularly encountered people of varying ethnicities, speaking a host of languages. Yet Israel does not distinguish among these races and nations. Instead, there is just ‘adam: one single human family. It is a remarkable confession, rejecting every form of racism and jingoistic nationalism.

It is particularly important that we translate ‘adam correctly, because Genesis 1:27 goes on very plainly to state:

“God created humanity in God’s own image,

in the divine image God created them,

male and female God created them.”

Both masculinity and femininity, both maleness and femaleness, are reflections of God in this text. There is no basis here for placing women under men. To be sure, Israel’s traditions were not always equal to this insight! Yet here it is, at the very beginning of the Bible. Sexism, like racism, is denied any place in God’s rightly ordered world.

Another surprise comes in the second version of the Ten Commandments, in the book of Deuteronomy (which in Greek means “second law”). Deuteronomy 5:21 reads:

“Do not desire and try to take your neighbor’s wife.

Do not crave your neighbor’s house, field, male or female servant, ox, donkey, or anything else that belongs to your neighbor.”

Both the break in the middle of this verse, and the different words used with regard to the neighbor’s wife and the neighbor’s property, are features of the Hebrew text of Deuteronomony. While in the Exodus 20 version, women are included in the neighbors “house” as property, the Ten Commandments in Deuteronomy make a clear distinction between the wife and the house: women are not property, here!

The Old Testament is filled with surprising stories about strong women taking the lead. Miriam, Moses’ sister, was a prophet (see Micah 6:4, which describes Miriam alongside Moses and Aaron as leading the Israelites to freedom). The prophet Deborah (Judges 4-5) unites the tribes of Israel against their enemies. Ruth, a poor Moabite widow, takes the first step in proclaiming her love to Boaz, and becomes the ancestress of King David. Esther risks her position and her life to stand up for her persecuted people.

In the Gospels, Jesus continually demonstrates concern for women (see the discussion of Jesus’ position on divorce in my earlier blog, “HWJR?”). John’s gospel describes the remarkable story of the Samaritan woman who meets Jesus at the well, talks with him, and becomes the first missionary! Jesus’ movement was supported by women (Luke 8:2-3). At the end, even when his disciples had forsaken him, the women remained, at the cross and at the tomb, so that it was women who were the first eyewitnesses to the resurrection.

In the letters of Paul, everywhere that the apostle offers personal greetings, he mentions women, by name. Romans 16 provides several fascinating examples: Paul greets Phoebe, who he calls a deacon (the CEB reads “servant,” but notice that this is the same Greek title given in Acts to male leaders like Philip and Stephen), Prisca and Aquila (a husband and wife ministry team; here as elsewhere, Paul breaks convention by mentioning the wife, Prisca, first), Mary, and most remarkably, Andronicus and Junia, another husband and wife team who are “prominent among the apostles”–Paul refers to Junia here as an apostle!

In 1 Corinthians 11:2-16, Paul insists that Corinthian women follow custom by wearing a head covering while prophesying: emphasizing a distinction between women and men. Still, this passage presupposes that women were speaking in the churches–Paul just wants them to do so respectfully!

Most remarkable of all is Paul’s bold proclamation in Galatians 3:28: “There is neither Jew nor Greek; there is neither slave nor free; nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” Since, for Paul, all of us have access to God through Jesus and Jesus alone, every earthly hierarchy has been overthrown. All of us approach God on an equal footing, women and men alike.

Viewed in the context of the whole of Scripture, then, we can understand the attitudes expressed in 1 Timothy 2:8-15 without feeling bound by them. In my tradition, for nearly as long as the Methodist movement has been in existence, women have been preaching. In 1787, John Wesley himself gave permission for Sarah Mallet to preach, holding her to standards no different than those expected of all Methodist lay preachers. However, it was a move severely criticized.

Many regarded women preachers as little more than a novelty; Samuel Johnson, upon hearing of women preaching in the Quaker movement, said, “Sir, a woman’s preaching is like a dog’s walking on his hind legs. It is not done well; but you are surprised to find it done at all.”

The powerful preaching of women evangelists such as Jarena Lee

and Phoebe Palmer

gave the lie to such condescending nonsense. But still, though women were recognized as evangelists or local pastors, they were mostly barred from ordination in the various denominations that would form the United Methodist Church (the former United Brethren being an occasional exception). Not until 1956, the year I was born, were women ordained in the former Methodist Church, a right expressly continued in 1968 when the Methodist and Evangelical United Brethren churches joined to form the United Methodist Church.

Tragically, still today, women in ministry face resistance and rejection. Rather like the eleven in Luke 24:11, who considered the women’s testimony about Jesus’ resurrection “nonsense,” too many of us refuse to hear the good news when proclaimed by a woman. But by refusing to hear God’s word proclaimed in a female voice, we close ourselves off from God. May the Lord open our minds and hearts and ears, to receive with joy the witness to our Lord’s death and resurrection that faithful women continue to bring.

AFTERWORD:

I apologize for the missed post last week–a cold and flu intervened. I will endeavor to post weekly. Thank you for staying with me through this brief hiatus.

With the publication of a fragmentary text from Cave 4 at Qumran (called 4QSam a), we now know that this story was part of the text of Samuel: a paragraph that fell out of the text in the course of its copying and recopying over generations. The NRSV of

With the publication of a fragmentary text from Cave 4 at Qumran (called 4QSam a), we now know that this story was part of the text of Samuel: a paragraph that fell out of the text in the course of its copying and recopying over generations. The NRSV of