Earlier this month, the Wesleyan Covenant Association (WCA) had its organizing meeting in Chicago. Prior to the meeting, an article in the online Religion News Service opened with this paragraph:

Earlier this month, the Wesleyan Covenant Association (WCA) had its organizing meeting in Chicago. Prior to the meeting, an article in the online Religion News Service opened with this paragraph:

Undoing the election of the first openly lesbian bishop in the United Methodist Church will be a primary goal when 1,500 Methodist evangelicals gather this week in Chicago to found a new renewal group, according to organizers.

The article quoted Rev. Jeff Greenway, a leading figure in the movement:

“There are statements we’re making in regard to the acts of covenant-breaking that have accelerated the frequency and seriousness of the situation we’re in,” Greenway said. Such acts include “not only the election of Bishop Oliveto, but also the approval of four openly gay clergy in the New York Annual Conference” and similar steps taken elsewhere, he said.

The WCA will insist “that the commission proposes a plan that calls for accountability and integrity to our covenant and restores the good order of the church’s polity,” Greenway said.

I have many friends, colleagues and students, who were in attendance in Chicago; they, and others, have said that this meeting was not about human sexuality, but about Christian fellowship and sharing the Gospel. Many of those friends and I do disagree, on this issue and on others–but we are still brothers and sisters in Christ! Certainly, Christians who love the Lord and the Bible may, nonetheless, differ in their interpretation and application of Scripture.

But official statements of the WCA go further than acknowledging differences. A FAQ on their website (now unavailable) read:

Pastors and congregations have expressed an interest in creating a “place” where traditional, orthodox UM churches can support and resource each other – both for ministry to our changing culture and for facing the challenges presented by a denomination that is unclear about its commitment to Scripture.

I do not believe that I or other United Methodist Christians like me are at all “unclear about [our] commitment to Scripture.” I am absolutely clear about my commitment to Scripture. Indeed, I believe that God has called me to the study and teaching of the Bible–that is why I am, after all, a Bible Guy! However, at least some in this movement have a very different idea than I do about what the Bible is.

If the above statement, posted by Rev. Rob Renfroe and the Wesleyan Covenant Association, truly expresses their approach to the Bible, then they regard the Bible as an end: “the Bible is indeed the Word of God [emphasis mine], and it’s not our job to twist or correct it.” I, on the other hand, believe that the Bible is a means: that it is Jesus Christ, Second Person of the Trinity, who is the Word of God (John 1:1-14), and that Scripture, rightly and prayerfully read, leads us into a relationship with God.

I am not alone in viewing Scripture as a means rather than an end. In a letter to a Mrs. Johnson, on November 8th, 1952, C. S. Lewis wrote:

It is Christ Himself, not the Bible, who is the true Word of God. The Bible, read in the right spirit and with the guidance of good teachers will bring us to Him. When it becomes really necessary (i.e. for our spiritual life, not for controversy or curiosity) to know whether a particular passage is rightly translated or is Myth (but of course Myth specially chosen by God from among countless Myths to carry a spiritual truth) or history, we shall no doubt be guided to the right answer. But we must not use the Bible (our ancestors too often did) as a sort of Encyclopedia out of which texts (isolated from their context and read without attention to the whole nature and purport of the books in which they occur) can be taken for use as weapons.

If the Bible is indeed a means rather than an end, then reading and applying Scripture must mean more than looking up “what the Bible says” about any particular issue, and then stating that as our position, without “twisting or correcting it.” Indeed, no one actually reads the Bible in that way, whatever their rhetoric may claim. In Leviticus 20, not only gay men (Lev 20:13), but also disrespectful children (Lev 20:9) and adulterers (Lev 20:10) are condemned to death–but few if any of us would regard this as God’s command for us. So too, we understand that when Jesus says, “If your hand causes you to fall into sin, chop it off” (Mark 9:43), he is not literally calling for us to dismember ourselves.

Recently, Wendy and I saw “Sully,” director Clint Eastwood’s cinematic take on the famous “Miracle on the Hudson” in January 2009. After the failure of both engines on US Airways Flight 1549, pilot Chesley Sullenberger (played in the film by Tom Hanks) landed his plane safely on the Hudson River, with no loss of life. The film focused particularly on the investigation that followed, in which Capt. Sullenberger was taken to task for not following the proper procedures. In his Patheos blog on this film, Paul Asay writes:

We learn that Sully acted from his gut—instinct informed by decades of experience. “I eyeballed it,” he admits. He tossed the rules and did what he thought was the right thing to do. And while investigators into the incident aren’t so sure, everyone aboard the plane is. “If he had followed the d–n rules we’d all be dead,” says co-pilot Jeff Skiles.

“Sully” could prove a cautionary tale about the dangers of reading Scripture–or rather, of taking one particular reading of Scripture–as a fixed and inflexible rulebook. As Asay observes,

All the rules that Sully disregarded, those were the best rules that could be put together via human understanding. They were good as far as they went, but they, like their authors, weren’t perfect. They couldn’t see into every eventuality. As Sully says, “Everything is unprecedented until it happens for the first time.”

We can’t trust our hearts. Not really. And yet there’s something in that heart that, if we’re focused on the right things, points us in the right direction. We don’t need to be told. We don’t need to rely on human understanding. Sometimes, I believe, God speaks through our gut.

If the Bible is a means rather than an end, then we cannot read it as a list of rules for life. We must rather listen carefully for the voice of the Living Word of God speaking through the words of Scripture. We must be attentive to the “still, small voice” of the Holy Spirit–speaking, perhaps, through our gut! After all, as the author of Hebrews declares, God’s Word in Scripture is no fixed and unchangeable “dead letter”:

God’s word is living, active, and sharper than any two-edged sword. It penetrates to the point that it separates the soul from the spirit and the joints from the marrow. It’s able to judge the heart’s thoughts and intentions (Heb 4:12).

Of course, trusting the Spirit is scary! I suspect that the real concern of people who speak as Rev. Renfroe does is not the need to uphold some standard of biblical literalism. It is, rather, the fear that without clear dividing lines, there will be no standards for morality at all. When those lines are drawn based on a particular way of reading and applying Scripture, questioning that reading becomes unacceptable. This is what the Bible says, because this is what the Bible must say: to claim otherwise is to be “unclear about [one’s] commitment to Scripture.”

The Fundamentalist movement began in America in the early twentieth century as a response to modernity–and particularly, to the threat that modernity was believed to pose to the foundations of a moral society. Its founders believed that only by recovering the “fundamentals” of Christianity, built on an inerrant and infallible Bible–THE Word of God–could the church meet that threat. Reading the Bible as a means rather than an end calls that approach into question. That does not mean, however, that our lives have no foundation–only that the lines may not fall where we had thought that they did.

My friend and colleague in United Methodist ministry Michael McKay calls us to a different kind of “fundamentalism.” Mike writes:

Lots of people will tell you that much of the violence and hatred

in the world is because of people who take their religion too seriously.

They get locked into a narrow view of the world

that has no room for anything but what they believe

and those who are different from them are treated

as the enemy.

The thinking goes that if we could get religious fundamentalists

to relax a little bit…things would be a lot better.

But…have you ever met an Amish terrorist?

By anyone’s definition the Amish are fundamentalist

in their outlook on life and their faith.

But they don’t blow up or shoot the people

they don’t agree with, in fact when a man

took hostages and killed several girls at

an Amish school before he killed himself

the Amish elders went to his house to tell

his family that they forgave him and to give

them an offering that had been taken up

among the Amish community.

Amish folks attended the funeral of the man

who killed their children.

Perhaps the main issue is not being

a religious fundamentalist, but maybe

the issue is what your fundamental is.

For the vast majority of Christians, Jews,

and Muslims our fundamental is loving and obeying

God through concrete acts of devotion and service.

I am beginning to think that to face the

scourge of violence and division that plagues

our world we need to get even more deeply

in touch with the fundamentals of what we

believe and practice them…

Getting in touch with our “fundamentals” will require us to ask hard questions about ourselves and our world. It will mean digging deeply into Scripture so that through its ancient witness we may ourselves encounter the Lord Jesus, and hear his command to us in our own time and place:

I give you a new commandment: Love each other. Just as I have loved you, so you also must love each other (John 13:34).

AFTERWORD: My friend Mike McKay would want me to give credit where credit is due by including his disclaimer: “You are more than welcome to use those thoughts in a Bible Guy post, but they did not originate with me. I heard the idea of an Amish terrorist from Tim Keller of Redeemer Pres. in Manhattan.”

.svg/2000px-Great_Seal_of_the_United_States_(obverse).svg.png)

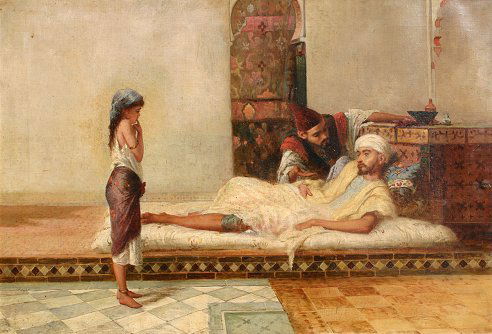

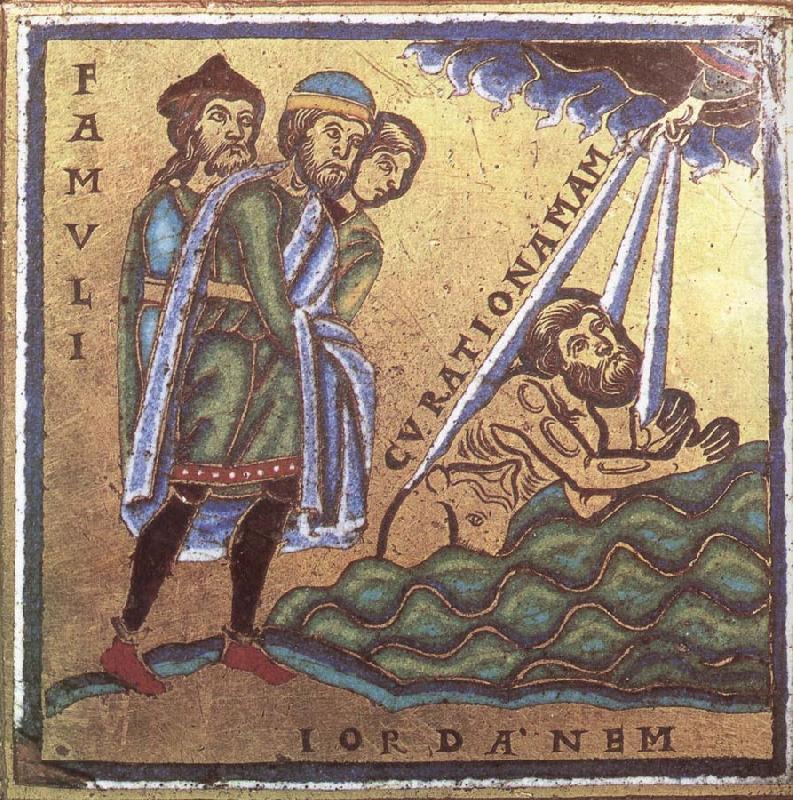

Which brings us to the healing of Naaman the leper, in

Which brings us to the healing of Naaman the leper, in

In this tragic biblical narrative, Tamar, the daughter of King David, is raped by her half-brother Amnon. Tamar is invisible to the men in this story: abused by her half-brother, ignored by her father. Even her brother Absalom’s revenge killing of Amnon is less an act of vengeance for Tamar than a self-serving assassination: with Amnon removed, Absalom is next in line for his father’s throne.

In this tragic biblical narrative, Tamar, the daughter of King David, is raped by her half-brother Amnon. Tamar is invisible to the men in this story: abused by her half-brother, ignored by her father. Even her brother Absalom’s revenge killing of Amnon is less an act of vengeance for Tamar than a self-serving assassination: with Amnon removed, Absalom is next in line for his father’s throne. Tamar’s story also raises other questions. To our (modern) astonishment, Tamar begs her rapist to marry her!

Tamar’s story also raises other questions. To our (modern) astonishment, Tamar begs her rapist to marry her!