A major shortcoming of today’s rich online and media environment, with thousands of sources to choose from for our education, information, and entertainment, is that we can heed those we like, and ignore those we don’t. As a result, we can surround ourselves with voices telling us what we already believe to be the case, and persuade ourselves that every reasonable person on earth thinks–or indeed, has always thought–just as we do.

This creates a major problem when we turn to the ancient and venerated text of the Bible. We may think that our questions are no different than those posed by the original audience of the text. We may even persuade ourselves that our cherished assumptions were also held by the writers of Scripture. We may, in short, naively assume that our reading is the right reading: the plain meaning of the text for everyone and anyone–to the end that, sadly, the Bible winds up confirming our own prejudices, and telling us, in the end, nothing that we did not already know.

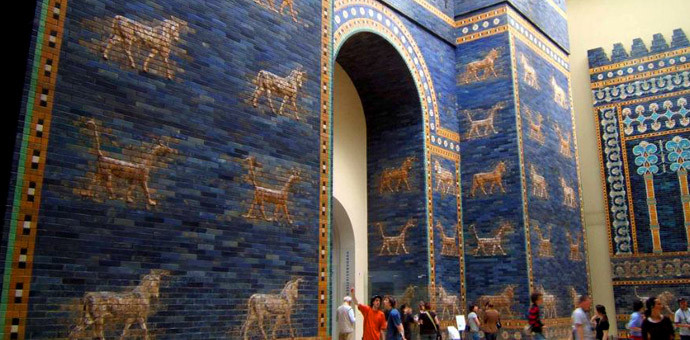

A moment’s thought dispels these deceptions. For the Bible is old: speaking to us from as far as three thousand years in the past (the likely date of the ancient Song of the Sea in Exodus 15:1-18, probably the oldest passage in Scripture), and expressing traditions and memories even older than its oldest written texts. The Bible was written in languages foreign to us: classical Hebrew, Aramaic, ancient Greek. Its traditions were formed and preserved in cultures very different from ours–and in many cases, different even from one another. This means that those of us reading the Bible in English must remind ourselves continually as we read that any particular word or concept, translated from its original language and context into ours, may have meant something very different to them than that same word means to us.

A moment’s thought dispels these deceptions. For the Bible is old: speaking to us from as far as three thousand years in the past (the likely date of the ancient Song of the Sea in Exodus 15:1-18, probably the oldest passage in Scripture), and expressing traditions and memories even older than its oldest written texts. The Bible was written in languages foreign to us: classical Hebrew, Aramaic, ancient Greek. Its traditions were formed and preserved in cultures very different from ours–and in many cases, different even from one another. This means that those of us reading the Bible in English must remind ourselves continually as we read that any particular word or concept, translated from its original language and context into ours, may have meant something very different to them than that same word means to us.

Ubiquitous cautions in London’s subway system, the Tube, warn about the space between the platform and the train: “Mind the Gap.” In our Bible reading, we too must carefully and prayerfully mind the gap between ourselves and the text.

To take a fairly innocuous, noncontroversial example, consider the word “bishop.” This year, the United Methodist Church will hold its Jurisdictional and Central Conferences, at which new Bishops will be elected. Delegates to those conferences will prepare for this serious task by doing Bible study–as well they should. But simply looking up the word “bishop” in Bible concordances and considering “what the Bible says about bishops” is not likely to be helpful.

Two passages are often held to relate the “biblical teaching” concerning the office of bishop. In the King James Version, 1 Timothy 3:2 reads,

A bishop then must be blameless, the husband of one wife, vigilant, sober, of good behaviour, given to hospitality, apt to teach (so too the NRSV).

Likewise, Titus 1:7-9 says:

If any be blameless, the husband of one wife, having faithful children not accused of riot or unruly. For a bishop must be blameless, as the steward of God; not selfwilled, not soon angry, not given to wine, no striker, not given to filthy lucre; But a lover of hospitality, a lover of good men, sober, just, holy, temperate; Holding fast the faithful word as he hath been taught, that he may be able by sound doctrine both to exhort and to convince the gainsayers (KJV; again, compare NRSV).

Our first problem is that the proper translation of the Greek word episkopos (rendered “bishop” in the passages above) is uncertain. The NIV reads “overseer” instead of bishop, and the CEB has “supervisor” in these same passages. Both are consistent with the use of this term in the Septuagint, the Greek translation of Jewish Scripture, where episkopos translates various words related to the Hebrew paqad, referring to duty, responsibility, or some official position of authority (for example, Numbers 4:16 or Nehemiah 11:9). Elsewhere in the New Testament, episkopos refers to a church office in Philippians 1:1 (compare the NRSV), but is also used in 1 Peter 2:25 for Jesus, “the shepherd and guardian [Greek episkopon] of your lives” (compare the KJV!). In Acts 20:28, Paul tells the elders of the church in Ephesus,

Watch yourselves and the whole flock, in which the Holy Spirit has placed you as supervisors [Greek episkopoi], to shepherd God’s church, which he obtained with the death of his own Son.

So, whom did New Testament episkopoi oversee or supervise: A single congregation (as Paul’s farewell to the Ephesian elders implies, and as is often the case in modern African American churches)? Many congregations in an area (as bishops do in my own tradition)? Christians generally? We do not know–making the application of these passages to our context difficult.

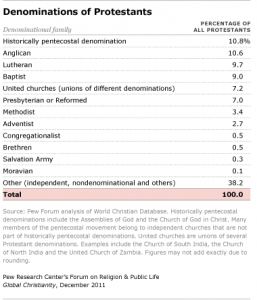

Indeed, we need to ask whether the word episkopos meant at all for the first readers of Timothy and Titus what “bishop” means for United Methodist Christians. Even in the contemporary church, “bishop” means something very different in, say, Roman Catholicism, or in African American Baptist traditions, than it means for United Methodists. The officials of the early church who are called “bishops” in the KJV and NRSV (among other translations) clearly differ from United Methodist bishops in multiple ways.

For example, it is evident from these biblical passages that episkopoi were to be men–not surprising, since 1 Timothy 2:8-15 denies women the right to preach or lead:

Adam wasn’t deceived, but rather his wife became the one who stepped over the line because she was completely deceived (1 Tim 2:14).

We don’t need to take the author of 1 Timothy’s word for what the text says, of course–we can look up Genesis 3:12-13 for ourselves! There, sure enough, the man declares, “The woman you gave me, she gave me some fruit from the tree, and I ate” (Gen 3:12)–blaming not only Eve, but God, who had brought her to him. The woman in turn blames the snake: “The snake tricked me, and I ate” (Gen 3:13). God, however, buys none of this. As the narrative unfolds in Genesis 3:14-19, the man, the woman, and the snake are all held accountable, and each suffers the consequences of the choice made.

The claims in 1 Timothy notwithstanding, we don’t have to look hard to find examples of women in leadership in the earliest church. John’s gospel tells the remarkable story of the Samaritan woman who met Jesus at the well, talked with him, and became the first missionary. The work of Jesus and his followers was enabled by women of independent means “who provided for them out of their resources” (Luke 8:2-3). At the end, when his male disciples had forsaken him, the women remained, at the cross and at the tomb, so that it was women who were the first eyewitnesses to the resurrection.

In his letters, Paul mentions women leaders by name every time he offers personal greetings. Romans 16 provides several fascinating examples. First, there is Phoebe, whom Paul calls a diakonon (Rom 16:1)–the CEB reads “servant,” but diakonos, the Greek word found here in a feminine form, is the same title the tradition assigns to male servant leaders such as Philip and Stephen (see Acts 6:1-6): like them, Phoebe was a deacon. Prisca and Aquila (Rom 16:3-4) were a husband and wife ministry team; here as elsewhere, Paul breaks convention by mentioning the wife, Prisca (also called Priscilla), first. Paul also greets Mary (Rom 16:6), and most remarkably, Andronicus and Junia (Rom 16:7): another husband and wife team mentioned only here, but who Paul says are “prominent among the apostles.” Paul refers to Junia, a woman, as an apostle!

In 1 Corinthians 11:2-16, Paul insists that Corinthian women follow custom by wearing a head covering while prophesying: emphasizing a distinction in dignity between women and men. Still, this passage assumes that women were speaking in the churches–Paul just wants them to do so more respectfully. Most remarkable of all is Paul’s bold proclamation in Galatians 3:28:

There is neither Jew nor Greek; there is neither slave nor free; nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.

The attitudes expressed in Timothy and Titus must be read, not in isolation, but in the context of the whole of Scripture. A solid biblical argument can be made for female pastoral leadership, at every level of church life. In the United Methodist Church, women have been serving as bishops since 1980, when Rev. Marjorie Matthews was elected to that office. Currently, 15 women serve as United Methodist bishops worldwide.

The passages from Timothy and Titus assume that bishops are not only men, but married men–clearly not the case in the Roman Catholic context! Indeed, bishops must have had only one wife. Again, the United Methodist Church (with the exception of the church in Liberia) does not follow this practice, permitting divorce and remarriage for laity and clergy alike, including bishops–indeed, my own Bishop fits into this category. In short: it is by no means clear that the New Testament term sometimes rendered “bishop” has any simple relationship with the word “bishop” as my own Christian tradition–or for that matter, any contemporary church–uses it.

For millions of Western Christians, this Wednesday, January 6, will be the Feast of the Epiphany–a day associated particularly with

For millions of Western Christians, this Wednesday, January 6, will be the Feast of the Epiphany–a day associated particularly with

For Malachi, it is the LORD who is “the sun of righteousness,” rising with “healing. . . in its wings.” The Greek translation of Jewish Scripture, the Septuagint, as well as the Latin Vulgate, have “his wings” (see the

For Malachi, it is the LORD who is “the sun of righteousness,” rising with “healing. . . in its wings.” The Greek translation of Jewish Scripture, the Septuagint, as well as the Latin Vulgate, have “his wings” (see the

Fellow Whovians will recognize the reference to

Fellow Whovians will recognize the reference to

I love the scene in the first “Ghostbusters” movie where the team

I love the scene in the first “Ghostbusters” movie where the team

3) The Old Testament is odd.

3) The Old Testament is odd.