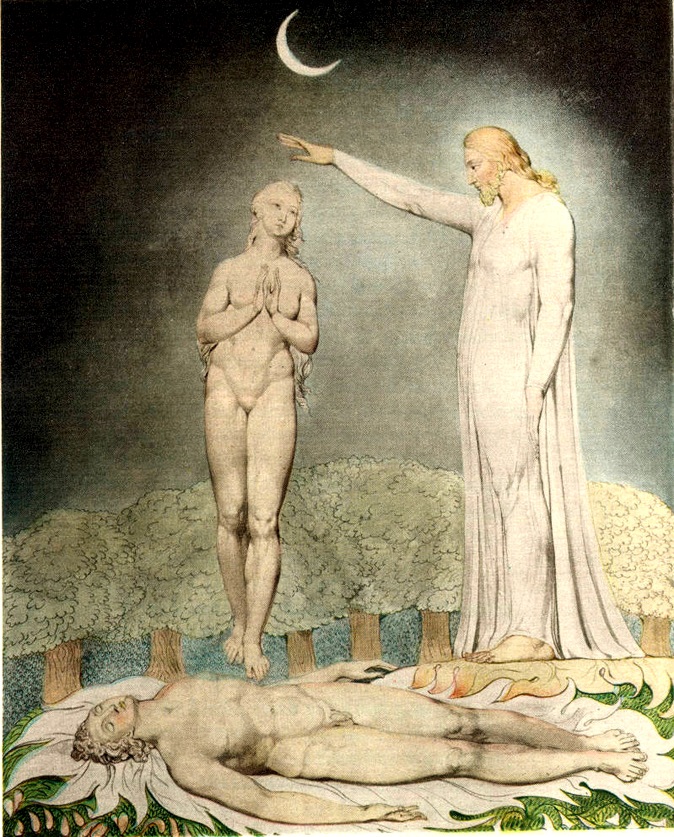

Both of the Genesis creation accounts refer not simply to God’s generic creation of humanity, but specifically to the creation of women and men. Genesis 1:27 says,

God created humanity in God’s own image,

in the divine image God created them,

male and female God created them.

Genesis 2 describes the special creation of the woman from the very stuff of the man. In its climax, this account of creation declares,

This is the reason that a man leaves his father and mother and embraces his wife, and they become one flesh (

Gen 2:24).

As we have seen, Jesus’ affirmation of marriage quotes both of these passages, grounding God’s intention for marriage in creation itself. Similarly, in his statement of opposition to same-sex relations in Romans 1, Paul makes reference to God’s will manifest in creation, although he does not quote from Genesis in this context. He does cite Gen 2:24 in reference to sexual immorality, however: “Don’t you know that anyone who is joined to someone who is sleeping around is one body with that person? The scripture says, The two will become one flesh” (1 Cor 6:16; compare Ephesians 5:31-32, which reads this passage as a metaphor for the unity of Christ and the church).

Many interpreters have concluded that Genesis presents the union of male and female as God’s intention for humanity, and indeed for all the natural world. By this reading, same-sex intercourse, since it does not involve a union of differences, violates God’s will. New Testament scholar N. T. Wright, who is inclined toward this view, proposes that human sexuality needs to be viewed as a part of “God’s differentiated creation, which nevertheless is designed to work together.”

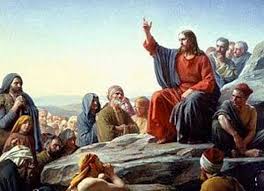

The official stances of the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches on marriage and sexuality further derive from Genesis the foundations of a natural law regarding human sexuality. Since, as the early Christian theologian and scholar St. Jerome (340-420) observed, “God’s first command” is, “‘Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth'” (Against Jovinianus, 1.3; see Gen 1:28), this approach holds the purpose of sexual intercourse to be procreation. Since same-sex intercourse cannot result in children, then, it violates this natural law.

United Methodist pastor and scholar Maxie Dunham has spoken in support of the United Methodist Church’s position rejecting homosexuality, as stated in The 2012 Book of Discipline (p. 109), on the ground of harmony with this teaching of the whole church. He writes:

United Methodist pastor and scholar Maxie Dunham has spoken in support of the United Methodist Church’s position rejecting homosexuality, as stated in The 2012 Book of Discipline (p. 109), on the ground of harmony with this teaching of the whole church. He writes:

This is the corporate, and continuing witness of the Church. We need to keep in mind that how we think must not be restricted to random feelings and even individual interpretation of Scripture; We need to be in harmony with the whole Body of Christ and all the saints now and forever.

The natural law argument, in various forms, is very old. The Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria (20 BC-50 A.D.) objected to the Greco-Roman custom of pederasty in part on this basis:

. . . the man who is devoted to the love of boys [Greek paiderastes] . . . pursues that pleasure which is contrary to nature, and since, as far as depends upon him, he would make the cities desolate, and void, and empty of all inhabitants, wasting his power of propagating his species (Special Laws 3.7.39).

So too the Wisdom of Solomon, a first-century B.C. book of Jewish wisdom, not only attributes the sexual immorality of the Gentile world to idolatry (compare Wisd 14:22-26 to Rom 1:18-32), but also defines one aspect of that immorality (see Wisd 14:26) as geneseos enallage, literally “the alteration of generation”–that is, engaging in sexual acts that cannot result in offspring.

Christian ideas of natural law, especially relating to sex and procreation, derive particularly from the work of St. Augustine of Hippo (354-371). Augustine’s Pelagian adversaries, who rejected the doctrine of original sin (the teaching that humans are by nature sinners), argued that accepting the notion of original sin would require one to condemn marriage itself, since sexual intercourse must therefore be held as inherently sinful. Indeed, even Jerome taught,

. . . while we honour marriage we prefer virginity which is the offspring of marriage. Will silver cease to be silver, if gold is more precious than silver? Or is despite done to tree and corn, if we prefer the fruit to root and foliage, or the grain to stalk and ear? Virginity is to marriage what fruit is to the tree, or grain to the straw (Against Jovinianus, 1.3).

To the implication that the Christian seeking to avoid sin should remain celibate, Augustine replied,

the marriage of believers converts to the use of righteousness that carnal concupiscence by which “the flesh lusteth against the Spirit.” For they entertain the firm purpose of generating offspring to be regenerated—that the children who are born of them as “children of the world” may be born again and become “sons of God” (On Marriage and Concupiscence, 1.5.iv.)

Still, according to Augustine, producing little Christians is all that sex is good for: “The union, then, of male and female for the purpose of procreation is the natural good of marriage. But he makes a bad use of this good who uses it bestially, so that his intention is on the gratification of lust, instead of the desire of offspring” (On Marriage and Concupiscence, 1.5.iv.). This, of course, means that same-sex relations must be condemned–but that is not all that it means. By this logic, heterosexual intercourse simply for pleasure, even with one’s spouse, is also sinful. Although this sin may be only venial (that is, a sin that damages, but does not break, one’s communion with God), it may become mortal sin:

It is, however, one thing for married persons to have intercourse only for the wish to beget children, which is not sinful: it is another thing for them to desire carnal pleasure in cohabitation, but with the spouse only, which involves venial sin. For although propagation of offspring is not the motive of the intercourse, there is still no attempt to prevent such propagation, either by wrong desire or evil appliance. They who resort to these, although called by the name of spouses, are really not such; they retain no vestige of true matrimony, but pretend the honourable designation as a cloak for criminal conduct (On Marriage and Concupiscence, 1.17.xv.)

Contraception (“evil appliance”), non-genital intercourse, and any other “wrong desire”–that is, any sex that cannot potentially produce a child–is a mortal sin, leading to damnation.

The natural law argument reached its most developed, closely reasoned form in the writings of St. Thomas Aquinas (1226-1274), particularly his massive Summa Theologica. There, for example, Aquinas reasons that, even if there had been no fall, there would still have been generation by means of sexual intercourse, as “what is natural to man was neither acquired nor forfeited by sin”: therefore sex is not, in itself, sinful (Summa Theologica Part 1, Question 98, “Of the Preservation of the Species,” Article 2). In the Supplement to Part 3 of the Summa (Question 49, “Of the Marriage Goods,” Article 6) Aquinas poses Augustine’s question, “Whether it is a mortal sin for a man to have knowledge of his wife, with the intention not of a marriage good [according to Augustine, these goods are “offspring, fidelity, the sacramental bond” (On Marriage and Concupiscence, 1.19.xvii.)] but merely of pleasure?”

Aquinas reaches a somewhat different conclusion than Augustine had, in no small measure because he views pleasure differently. To understand pleasure, he turns for guidance to Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics 10:3-4, where the philosopher concludes:

One might think that all men desire pleasure because they all aim at life; life is an activity, and each man is active about those things and with those faculties that he loves most. . . now pleasure completes the activities, and therefore life, which they desire. It is with good reason, then, that they aim at pleasure too, since for every one it completes life, which is desirable. But whether we choose life for the sake of pleasure or pleasure for the sake of life is a question we may dismiss for the present. For they seem to be bound up together and not to admit of separation, since without activity pleasure does not arise, and every activity is completed by the attendant pleasure.

Since, Aquinas observes, “the same judgment applies to pleasure as to action, because pleasure in a good action is good, and in an evil action, evil; wherefore, as the marriage act is not evil in itself, neither will it be always a mortal sin to seek pleasure therein.” Still, like Augustine, Aquinas argues that “if pleasure be sought in such a way as to exclude the honesty of marriage, so that, to wit, it is not as a wife but as a woman that a man treats his wife, and that he is ready to use her in the same way if she were not his wife, it is a mortal sin; wherefore such a man is said to be too ardent a lover of his wife, because his ardor carries him away from the goods of marriage.” Once more, sexual activity is held to be mortally sinful if divorced from its purpose, namely procreation.

The positions of Augustine and Aquinas on human sexuality are still, in large measure, the official doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church, reaffirmed by Pope Pius XI in his encyclical Casti Connubii (“On Chaste Marriage,” 1930), by Pope Paul VI in Humanae Vitae (“Of Human Life,” 1968), and by Pope John Paul II in Evangelium Vitae (“The Gospel of Life,” 1995). But the effectiveness of the Church in persuading its followers to embrace and live by this teaching is another matter. A recent poll of Roman Catholics worldwide, conducted by the American Spanish-speaking television network Univision, found that 78% of respondents support the use of contraceptives–ranging from 91% in Latin America to 31% in the Philippines. So too, a majority (58%) disagreed with the statement, “An individual who has divorced and remarried outside of the Catholic Church, is living in sin which prevents them from receiving Communion.”

The natural law argument, followed consistently, takes us to places most of us would rather not go. But given our proclivity for self-deception and sin, that need not mean that the argument is invalid. The notion that sexual pleasure for its own sake is inherently sinful is, however, scarcely compatible with the goodness of the physical world and of embodied existence emphasized throughout the Hebrew Bible.

Repeatedly, the first creation account (Gen 1:1–2:4a), tells us what God thinks of the world God is calling into being: “God saw how good it was” (1:4, 10, 12, 18, 25)! Then, after the work is done and before God’s sabbath rest, the text declares, “God saw everything he had made: it was supremely good” (1:31). In Proverbs 8:30-31, God’s Wisdom declares her delight in God’s creation, and particularly, in humanity:

I was beside [God] as a master of crafts.

I was having fun,

smiling before him all the time,

frolicking with his inhabited earth

and delighting in the human race.

In the Song of Songs, there is a frank recognition and celebration of human sexual passion that is certainly about more than child-bearing!

Set me as a seal over your heart,

as a seal upon your arm,

for love is as strong as death,

passionate love unrelenting as the grave.

Its darts are darts of fire—

divine flame!

Rushing waters can’t quench love;

rivers can’t wash it away.

If someone gave

all his estate in exchange for love,

he would be laughed to utter shame (Song 8:6-7)

The apostle Paul too affirms the inherent goodness of sexual intimacy in marriage:

The husband should meet his wife’s sexual needs, and the wife should do the same for her husband. The wife doesn’t have authority over her own body, but the husband does. Likewise, the husband doesn’t have authority over his own body, but the wife does. Don’t refuse to meet each other’s needs unless you both agree for a short period of time to devote yourselves to prayer. Then come back together again so that Satan might not tempt you because of your lack of self-control (1 Cor 7:3-5).

When we read the opening chapters of Genesis, it is important for us to remember that they are neither history, nor science, nor law. They are confessions, made by communities of faith–grounded not only in universal, timeless ideas but also in the particular circumstances of their authors. The affirmation in Gen 1:27 that maleness and femaleness alike reflect the image of God hits like a thunderbolt: it can scarcely be ascribed to the typical attitudes of its patriarchal culture! This extraordinary valuation of the feminine need not be read, however, as restricting God’s intention for humanity to the union of male and female. Certainly Jerome, with his eloquent defense of celibacy, did not regard singleness as condemned by this passage!

On the other hand, the call to “Be fertile and multiply; fill the earth and master it” (Gen 1:28) is no surprise: it fits neatly into the flow of the narrative from Genesis through Joshua.

As God’s people endure threat after threat, seeming always on the edge of extinction, the imperative to be fertile is essential for their survival. In particular, Gen 1:28 prefigures the growth of the people into a great nation, despite Egyptian persecution (see Exod 1:6-7, 20) and despite the faithlessness of the wilderness generation (see Num 22:3-4), in fulfillment of God’s promise to Abraham (see Gen 15:5-6). We may question, then, whether this “first commandment” is intended as a universal imperative.

Similarly, as an etiological narrative, Genesis 2 seeks to make sense of the world that Israel inhabited. Specifically, this account of man and woman as parts of an original whole is an attempt to come to terms with both the generative and the potentially disruptive power of sexual attraction in Israel’s clan-based culture: “This is the reason that a man leaves his father and mother and embraces his wife, and they become one flesh” (Gen 2:24).

This verse, then, is an explanation, not a commandment; it is descriptive, not prescriptive–just as Jesus’ quotation of this passage is an affirmation, not a prohibition. That Genesis 2 deals with the dominant (and, in its Israelite context, the only officially sanctioned) mode of sexuality in human culture is scarcely surprising: after all, the survival of the culture through the birth of children, as well as the threat posed to the culture by a force stronger than loyalty to one’s clan, are alike in the background of this passage. But again, Genesis 2 is a narrative, not a law code.

While we must of course recognize and honor the power of tradition to give shape to our experience of God and the world, it is God, not tradition, that we worship. Dr. Dunham does not acknowledge that many faith communions have indeed already departed from traditional views of marriage and sexuality. The United Methodist Church, for example, permits remarriage after divorce, offers no objection to contraception, and practices the ordination of women. Churches with which we are in full communion, such as the Presbyterian Church (USA) and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America, ordain LGBTQ persons.

A final word must be spoken. While sexual intimacy is an important part of any healthy marriage, it is far from the only part. LGBTQ people seeking marriage do not do so simply out of sexual desire, any more than heterosexual couples do. They want to proclaim their love for one another before God and before their sisters and brothers in faith–embracing, in Augustine’s terms, the “marriage good” of fidelity. What is more, LGBTQ couples seeking marriage long to declare their covenantal commitment to one another: in the ancient words of the liturgy, to pledge to one another their faith–embracing the “marriage good” of lifelong commitment, if not, in Catholic terms, “the sacramental bond.” I see no barrier to that commitment in the Genesis accounts of creation.

AFTERWORD

Wendy, her brother Mark, and all our family thank all of you for your thoughts, prayers, calls, emails, cards, and gifts. Your support has meant the world to us: we have felt loved, lifted up in our sorrow by the body of Christ. We thank God for Mom, and give thanks for her life that in Christ will never end. May light perpetual shine upon you, Gerry!

In “Princess Bride,” one of my favorite films, a continuing shtick involves Wallace Shawn’s character, Vazzini, who uses the word “

In “Princess Bride,” one of my favorite films, a continuing shtick involves Wallace Shawn’s character, Vazzini, who uses the word “ In

In