When I visit my father, who turns 88 this month (Happy birthday, Daddy!). we often watch old movies together–especially old Westerns. You never have to wonder who the good guys are in those old oaters! They are always dressed the part: clean-cut, clean shaven, and wearing white hats. The villains by contrast are scruffy, mustachioed, and wear black.

When I visit my father, who turns 88 this month (Happy birthday, Daddy!). we often watch old movies together–especially old Westerns. You never have to wonder who the good guys are in those old oaters! They are always dressed the part: clean-cut, clean shaven, and wearing white hats. The villains by contrast are scruffy, mustachioed, and wear black.

So, when “Have Gun, Will Travel” appeared on television in 1957, it was something of a shock. Its main character, Paladin (expertly portrayed through its six-year run by Richard Boone), wasn’t a sheriff or a cowboy, but a gunfighter for hire. Paladin wore black. He looked, dressed, and often talked like a villain—yet he was the hero. Sometimes, in those short, often very well-written episodes, Paladin would wind up changing sides–fighting for the people he believed to be in the right, rather than the ones who had hired him.

So, when “Have Gun, Will Travel” appeared on television in 1957, it was something of a shock. Its main character, Paladin (expertly portrayed through its six-year run by Richard Boone), wasn’t a sheriff or a cowboy, but a gunfighter for hire. Paladin wore black. He looked, dressed, and often talked like a villain—yet he was the hero. Sometimes, in those short, often very well-written episodes, Paladin would wind up changing sides–fighting for the people he believed to be in the right, rather than the ones who had hired him.

The Gospel for this Sunday (Luke 18:9-14) is the short, very familiar parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector:

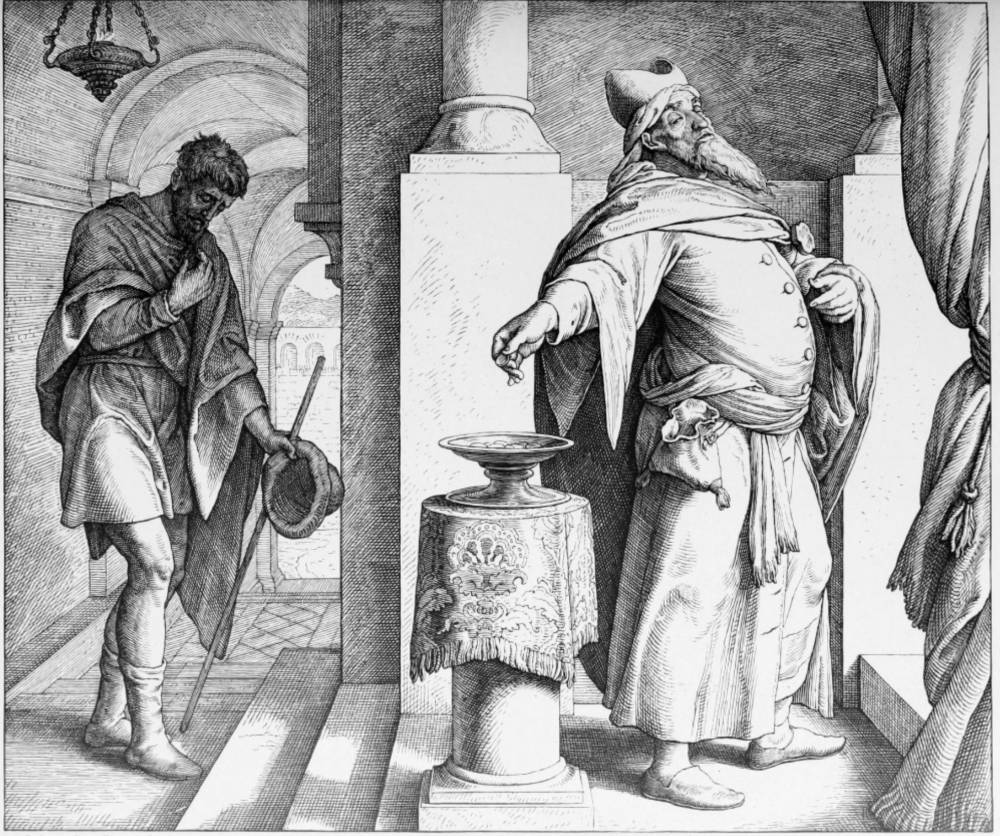

Jesus told this parable to certain people who had convinced themselves that they were righteous and who looked on everyone else with disgust: “Two people went up to the temple to pray. One was a Pharisee and the other a tax collector. The Pharisee stood and prayed about himself with these words, ‘God, I thank you that I’m not like everyone else—crooks, evildoers, adulterers—or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week. I give a tenth of everything I receive.’ But the tax collector stood at a distance. He wouldn’t even lift his eyes to look toward heaven. Rather, he struck his chest and said, ‘God, show mercy to me, a sinner.’ I tell you, this person went down to his home justified rather than the Pharisee. All who lift themselves up will be brought low, and those who make themselves low will be lifted up.”

When we read the gospels, we are already primed to believe that we know who the good guys and the bad guys are—and the Pharisees, who frequently appear as the opponents of Jesus, are definitely the bad guys! Indeed, in modern English, “Pharisee” can be a synonym for “hypocrite.”

But this was certainly not the case in Jesus’ day. In first century Palestine, the Pharisees were the advocates for the common people. Indeed, the differences between Jesus and the Pharisees are so intense in the Gospels because they are, in essence, family quarrels: in many ways, Jesus was closer to the Pharisees than to any other Jewish party in his day.

Unlike the priestly party, the Sadducees, the Pharisees were famous for tolerance and mercy in their court rulings. While the Sadducees were biblical literalists, the Pharisees held that the “oral Torah”–the teachings of the rabbis that interpreted and applied Scripture to life–also needed to be considered. As a result, the Sadducees rejected both belief in the afterlife and in the coming of the Messiah, as they saw neither explicitly stated in the Torah. Pharisees embraced both of these ideas. When the Pharisee describes his personal acts of piety, fasting and tithing, he is not exaggerating or boasting–this actually would have been his lifestyle.

Likewise, in the first century, the tax collector most definitely would have been seen as the villain. Tax collectors were collaborators with the Roman military occupation. They were famously corrupt, typically collecting from the people far more than the Romans actually demanded, and living well off the proceeds (Zacchaeus being a familiar biblical example). That is why people are so scandalized by Jesus eating and drinking with tax collectors (Matthew 9:9-12)

Likewise, in the first century, the tax collector most definitely would have been seen as the villain. Tax collectors were collaborators with the Roman military occupation. They were famously corrupt, typically collecting from the people far more than the Romans actually demanded, and living well off the proceeds (Zacchaeus being a familiar biblical example). That is why people are so scandalized by Jesus eating and drinking with tax collectors (Matthew 9:9-12)

The surprise twist for the original audience of this parable, as for the television audience of “Have Gun, Will Travel,” would have been that the “hero” of the story is the bad guy! One lesson of this parable, then, is that we shouldn’t assume we know who the good guys are! As frequently happens in Jesus’ stories, things are not as they seem on the surface.

The Pharisee in this story may be looking up, and the tax collector looking down, but it is the tax collector who seeks, and finds, God. In the end, the Pharisee sees only himself–and does not even see himself clearly! The honest penitence of the tax collector, on the other hand, leads him past self-examination to a true insight into God’s character. It is he, Jesus says, who “went down to his home justified” (Luke 8:14).

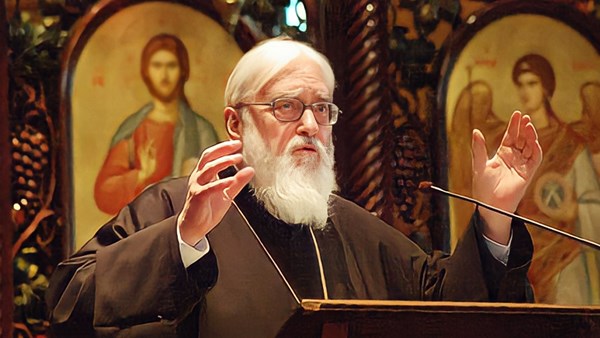

Regarding repentance, Metropolitan Kallistos Ware, who died this past year, wrote

[Repentance] is not self-hatred but the affirmation of my true self as made in God’s image. To repent is to look, not downward at my own shortcomings, but upward at God’s love; not backward with self-reproach, but forward with trustfulness. It is to see, not what I have failed to be, but what by the grace of God I can yet become.

God grant that this may be so for all of us, friends: that we may become, not what the world sees when it looks at us, or even what we ourselves see, but what God sees.