This Sunday is Valentine’s Day. In popular culture, the historical and religious connection with St. Valentine that gives the day its name was stretched past the breaking point long ago. We know Valentine’s Day as a day for lovers, and a celebration of romantic love. Its symbol is the heart, whether mailed as a valentine, given in candy form, texted as <3, or expressed as an emoji:

This Sunday is Valentine’s Day. In popular culture, the historical and religious connection with St. Valentine that gives the day its name was stretched past the breaking point long ago. We know Valentine’s Day as a day for lovers, and a celebration of romantic love. Its symbol is the heart, whether mailed as a valentine, given in candy form, texted as <3, or expressed as an emoji:

Since the Middle Ages, the heart has been the symbol of romantic love in the West, and regarded as the seat of the emotions and of sentiment. We commonly contrast thinking and feeling as matters of the head and the heart, respectively.

Today, of course, we are well aware of the difference between the symbol and the reality. We know that our hearts are actually powerful muscular pumps in our chests, which circulate life-giving, oxygen-bearing blood through our veins and arteries to every part of our bodies. If our heart ever stops beating, and does not start again, we die.

When our Bibles mention the heart, we are likely to think about one of these two concepts. The problem is, neither one was known to the Old or the New Testament authors, who did not connect the heart with emotions and did not understand the circulatory system! To understand what they would have meant by the heart requires us to set our preconceptions aside, and see with new (or more accurately, with ancient!) eyes.

A good way into understanding the heart in Scripture is Jesus’s teaching on the Great Commandment (Matthew 22:34-40; Mark 12:28-34; and Luke 10:25-28). In all three passages, Jesus’ teaching comes in a conversation with an expert on Jewish law, although the accounts differ on small points: in Matthew, the expert seeks to test Jesus; in Mark, his question is sincere; in Luke, it is Jesus who questions the expert! In all three, however, the answer is the same: no single commandment is the greatest. The meaning and message of Scripture hang not on one, but on two essential teachings: love for God, and love for neighbor.

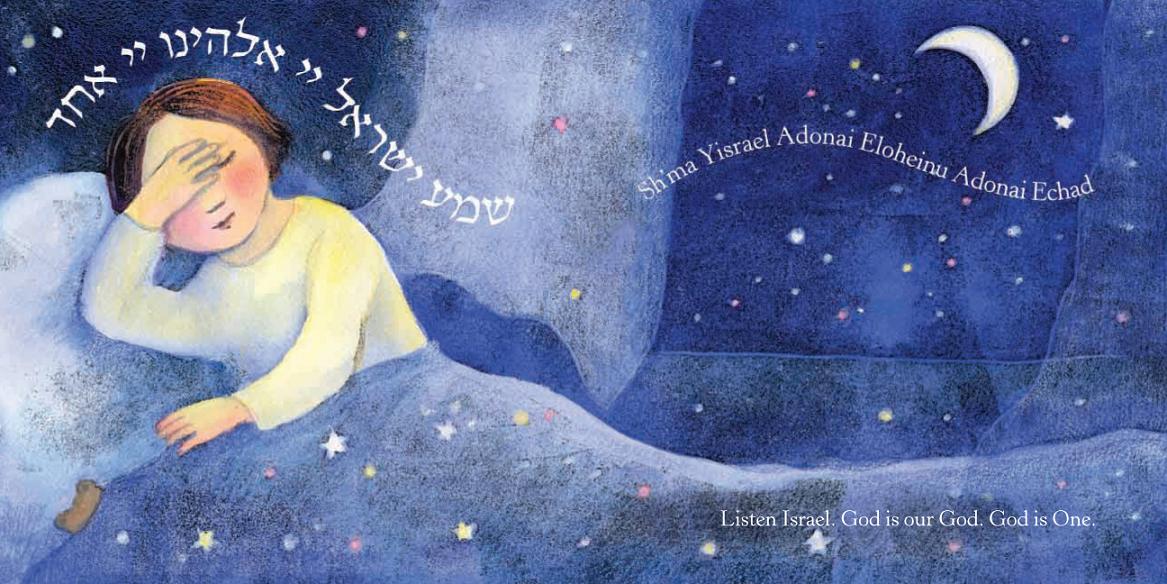

Jesus’ “first commandment” comes from the Shema’, which Mark’s version quotes in its entirety, and which still today is the heart of Jewish life and faith. The name comes from its first word in Hebrew: Shema’ Yisrael ‘Adonai ‘Elohenu ‘Adonai ‘echad. The traditional translation (see the KJV) of this verse, reflected in the Septuagint and in the Greek of Mark’s gospel, is: “Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God is one LORD.” A better rendering, though, is the one found in the Jewish Publication Society’s translation, and in the NRSV: “Hear, O Israel: The Lord is our God, the Lord alone.” While the traditional translation is an affirmation of the doctrine of monotheism (there is only one God), the better reading understands the Shema’ as a pledge of allegiance, a declaration of commitment: our God is the LORD, and only the LORD!

Jesus’ “first commandment” comes from the Shema’, which Mark’s version quotes in its entirety, and which still today is the heart of Jewish life and faith. The name comes from its first word in Hebrew: Shema’ Yisrael ‘Adonai ‘Elohenu ‘Adonai ‘echad. The traditional translation (see the KJV) of this verse, reflected in the Septuagint and in the Greek of Mark’s gospel, is: “Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God is one LORD.” A better rendering, though, is the one found in the Jewish Publication Society’s translation, and in the NRSV: “Hear, O Israel: The Lord is our God, the Lord alone.” While the traditional translation is an affirmation of the doctrine of monotheism (there is only one God), the better reading understands the Shema’ as a pledge of allegiance, a declaration of commitment: our God is the LORD, and only the LORD!

Deuteronomy 6:5, which immediately follows, describes the totality of that commitment: “Love the LORD your God with all your heart, all your being, and all your strength.” While some interpretations of this commandment find here three different ways of loving God, that does not seem to be its intent. The heart (lebab in Hebrew) is the center of the will: connected, not with feeling, but with deciding and doing. Loving God with all your heart, then, means choosing, as the opening verse of the Shema’ declares, to commit yourself solely and absolutely to God: to love God as much as you can.

The remainder of the verse restates and underlines this absolute commitment. Hebrew nephesh should not be translated as “soul.” Rather than some separate, immaterial part of me, nephesh refers, as the CEB translation “being” indicates, to the whole of me. To love God with all one’s nephesh is to love God entirely, with all that I am. The last word, typically translated “strength” or “might,” is me’od in Hebrew–not a noun, actually, but an adverb, meaning “much” or “very.” We are to love God with all our muchness–again, as much as we are possibly capable of loving!

In the Greek of the New Testament, however, and in the minds of early Christians influenced by Greek thought, this command does become a threefold (or more) depiction of loving God, with every aspect of one’s being. The KJV of Mark 12:30 reads,”And thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind, and with all thy strength.” The Greek psyche can refer (unlike Hebrew nephesh) to an immaterial, spiritual part of the person: hence, the soul. The Greek word dianoia refers to thoughts and intentions, and is commonly translated as “mind.” One’s “might” (Greek hischus) could be regarded as relating to one’s physical, material self.

First in the list, though, is the heart: Greek kardia. In Greek as in Hebrew, the heart is the center of the self–the choosing, deciding aspect of the person. Loving God with all one’s kardia is, on the right-hand side of the Bible, no more about feeling or sentiment than loving God with all one’s lebab on the left-hand side! In each case, love is a decision: an act of the will. Curiously, the association of love with the heart, in both the Hebrew Bible and in the New Testament, plainly demonstrates that love is not regarded here as an emotion. Love has to do, not with feeling or sentiment, but with the will. Love is a choice.

Jesus’ second “great commandment” makes this crystal clear. Leviticus 19:18 says, “you must love your neighbor as yourself; I am the LORD.” We could perhaps ask, as the lawyer does in Luke 10:29, “And who is my neighbor?” Indeed, some interpreters have proposed that this was an in-house commandment: “your neighbor” means “your fellow Israelite.” But Leviticus 19:33-34 demonstrates that this is far too narrow a reading. There, love is commanded toward “the alien who resides with you” (the Hebrew term is ger, meaning a non-Israelite living in the land without the comfort and protection of a clan) in the same language used in 19:18 for the neighbor: “you shall love the alien as yourself.” In fact this passage says, the ger “shall be to you as a citizen among you.” All quibbling aside, we already know this, as the lawyer in Luke’s account certainly would have known it. The real question, as Jesus’ famous story of the Good Samaritan demonstrates, is how can we demonstrate love–not just to those like us, and those we like, but to all our neighbors?

Actually, the fact that Scripture commands love for God and neighbor should already have made this clear. Feelings cannot be commanded–they simply are. Love for the neighbor doesn’t mean fond feeling: I may not even like my neighbor (at least, at first)! Love means willing and acting for my neighbors’ good, in order to bring about for them what I would wish for myself. Likewise, love for the LORD is not a sentimental valentine to God. Loving God is the decision to commit myself–my entire being–deliberately into God’s hands, and to live with the consequences. Making that choice, we discover that the deepest consequence of loving God is knowing that God loves us–that indeed, God loved us first!