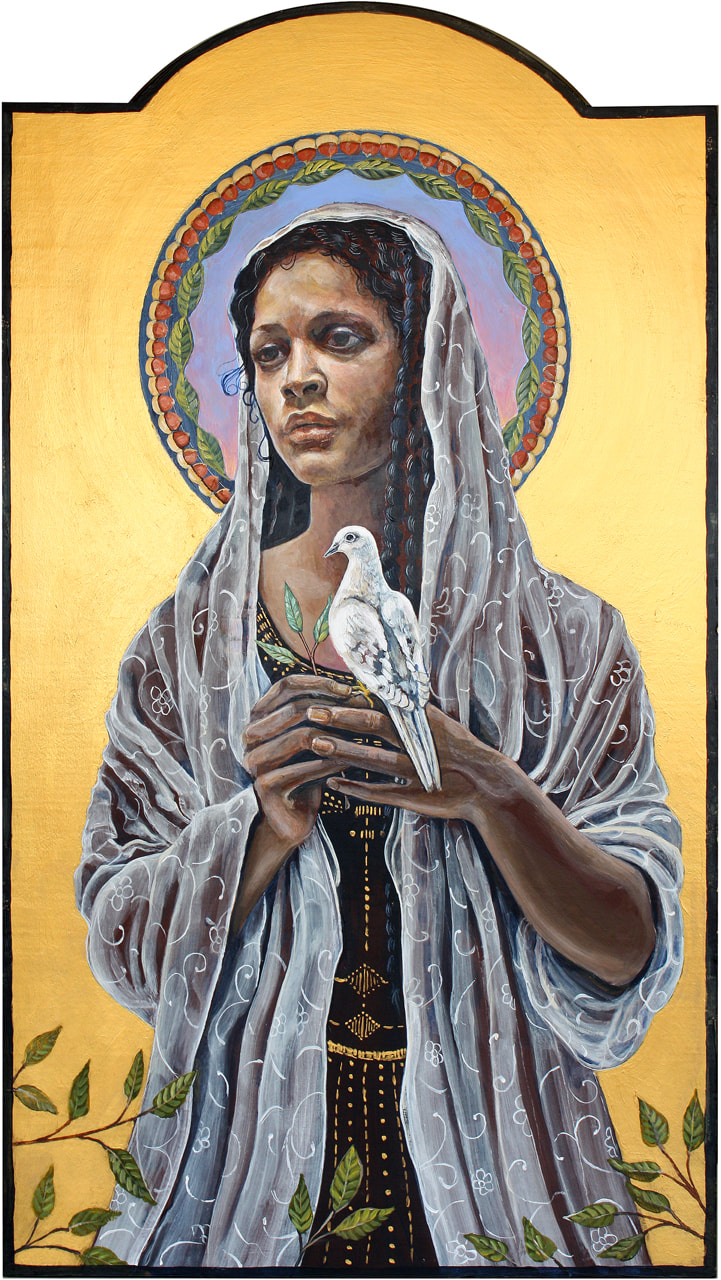

Today, July 22, is the feast of Mary Magdalene. All of the gospels (including the idiosyncratic Fourth Gospel; see John 20:1-18) agree that Mary Magdalene was an eyewitness to Jesus’ resurrection. But Luke in particular “emphasizes the priority of the women’s own experience over the angels’ words” (Charles H. Talbert, Reading Luke : A Literary and Theological Commentary on the Third Gospel [Crossroad, 1982], 227). The women see for themselves that the tomb is empty; then they hear the angels’ explanation (Luke 24:2-7; contrast Mark 16:6-8). The bravery and initiative of the women at the tomb in Luke contrasts with Mark’s gospel, where the witnesses “said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid” (Mark 16:8).

Today, July 22, is the feast of Mary Magdalene. All of the gospels (including the idiosyncratic Fourth Gospel; see John 20:1-18) agree that Mary Magdalene was an eyewitness to Jesus’ resurrection. But Luke in particular “emphasizes the priority of the women’s own experience over the angels’ words” (Charles H. Talbert, Reading Luke : A Literary and Theological Commentary on the Third Gospel [Crossroad, 1982], 227). The women see for themselves that the tomb is empty; then they hear the angels’ explanation (Luke 24:2-7; contrast Mark 16:6-8). The bravery and initiative of the women at the tomb in Luke contrasts with Mark’s gospel, where the witnesses “said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid” (Mark 16:8).

Luke identifies three of the group of brave women bearing witness to Jesus’ death, burial, and empty tomb by name: “It was Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James, and the other women with them who told these things to the apostles” (Luke 24:10). Mark identifies three and only three women (“Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome;” Mark 16:1), while Matthew names only two (“Mary Magdalene and the other Mary;” Matt 28:1). Still, all of the gospels agree that the first witnesses to Jesus’ resurrection were women, and that Mary Magdalene was present.

Two of the three women named in Luke’s account of Jesus’ resurrection are mentioned earlier in his gospel (Luke 8:2-3): Mary Magdalene, “from whom seven demons had been thrown out,” and Joanna, “the wife of Herod’s steward Chuza.” These two, together with “Susanna, and many others,” served as patrons for the ministry of Jesus and the twelve (Luke says that they “provided for them out of their resources;” Lk 8:3).

Somehow, Mary Magdalene came to be identified in Christian tradition with the “woman from the city, a sinner” in Luke’s account of the woman who anointed Jesus with fine ointment (Luke 7:36-50; compare Matt 26:6-13//Mark 14:3-9; in John 12:1-7, the woman who anoints Jesus is identified as another Mary, the sister of Martha and Lazarus!). This led to the common, but mistaken, notion that Mary Magdalene was a prostitute. Quite to the contrary, Luke presents her as a respectable matron of independent means, who was delivered from demonic possession by Jesus, and became his follower and supporter.

Mary Magdalene and Joanna are long-time followers and supporters of Jesus. The “other Mary” is likely the mother of two of the disciples. In short, these are reliable witnesses. However outlandish their story may appear, they have earned a respectful hearing.

But then, they are women. In first century Judaism, a woman’s testimony was not regarded as legally admissible. The Jewish historian Josephus wrote, “From women let not evidence be accepted, because of the levity and temerity of their sex” (Antiquities 4.8.15:219). So the eleven do not listen: “Their words struck the apostles as nonsense [Greek leros], and they did not believe them” (Luke 24:11). The greatest event in the history of the world is ignored because of the sexist small-mindedness of eleven men.

Only Peter takes the women with sufficient seriousness to check out their claim. Indeed, Peter “ran to the tomb; stooping and looking in, he saw the linen cloths by themselves” (Luke 24:12; compare John 20:6-7). This is an odd, but significant detail: why would a grave robber have unwound the grave cloths and left them behind? Certainly Peter has no explanation: “he returned home, wondering what had happened” (24:12). Still, he corroborates the women’s claims regarding the empty tomb: his is the second, independent witness required by Jewish law (Num 35:30; Deut 17:6; 19:15-21).

Rather like the eleven in Luke 24:11, who considered the women’s testimony about Jesus’ resurrection “nonsense,” too many refuse to hear the good news when proclaimed by a woman. Still, in my tradition, women have been preaching for nearly as long as the Methodist movement has been in existence. In 1787, John Wesley himself gave permission for Sarah Mallet to preach, holding her to standards no different than those expected of all Methodist lay preachers. However, it was a move severely criticized.

Many regarded women preachers as little more than a novelty; Samuel Johnson, upon hearing of women preaching in the Quaker movement, said, “Sir, a woman’s preaching is like a dog’s walking on his hind legs. It is not done well; but you are surprised to find it done at all.”

The powerful preaching of women evangelists such as Jarena Lee

and Phoebe Palmer

gave the lie to such condescending nonsense. But still, though women were recognized as evangelists or local pastors, they were mostly barred from ordination in the various denominations that would form the United Methodist Church (the former United Brethren being an occasional exception). Not until 1956, the year I was born, were women ordained in the former Methodist Church, a right expressly continued in 1968 when the Methodist and Evangelical United Brethren churches joined to form the United Methodist Church.

Tragically, still today, women in ministry face resistance and rejection. But by refusing to hear God’s word proclaimed in a female voice, we close ourselves off from God. Particularly on this feast of Mary Magdalene, may the Lord open our minds and hearts and ears, to receive with joy the witness to our Lord’s death and resurrection that faithful women continue to bring.