Rick Astley’s 1987 video “Never Gonna Give You Up” remains enormously popular, largely due to “Rickrolling“–a prank involving the unexpected insertion of the video, or the song, or its lyrics, into. . . well, pretty much anything. But this tweet caught my attention with its opening question: what, after all, is my favorite paradox?

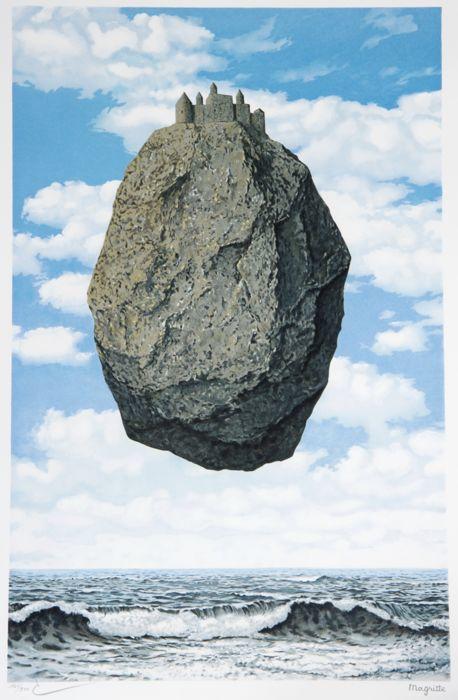

Way up there has to one of the infamous paradoxes of Divine omnipotence: If God is all-powerful, can God create a rock so heavy that God can’t lift it? Attempts to resolve this paradox lead into some unexpected, and quite sophisticated, theological insights.

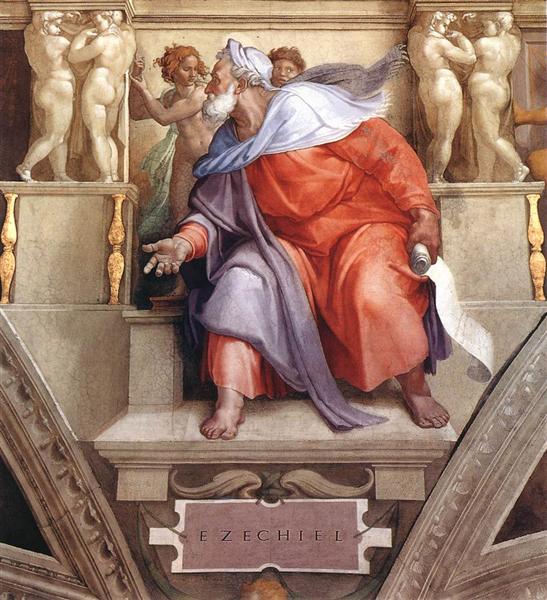

One possible answer to the riddle is, No. God can’t make a rock that God can’t lift–not because God’s power is lacking, but because God will never act contrary to God’s own character. Biblically, that solution seems likely to have appealed to the prophet Ezekiel. Some 72 times in his book, God acts, whether in judgment (for example, Ezek 7:4) or salvation (for example, Ezek 37:28), so “that they might know that I am the LORD.” Bible scholar Walther Zimmerli called this the Erkenntnisformel, or “recognition formula,” a motif that sums up the essence of Ezekiel’s message. As Zimmerli wrote,

The whole direction of the prophetic preaching is a summons to a knowledge and recognition of him who, in his action announced by the prophet, shows himself to be who he is in the free sovereignty of his person (Ezekiel 1, trans. Ronald E. Clements; Heremeneia [Philadelphia: Fortress, 1979], 40).

In other words, God does what God does because of who God is. Period.

The LORD acts for the sake of the LORD’s own honor and name–which is, in the end, extraordinarily good news. For Ezekiel, the history of God’s people has demonstrated that, if our hope for salvation depends upon our faithfulness, we have no hope at all (see Ezekiel 20). The only way that we can have any hope for the future is if our deliverance depends upon God’s character—not upon our worthiness, or even upon our repentance. Therefore, Ezekiel baldly states,

The LORD God proclaims: House of Israel, I’m not acting for your sake but for the sake of my holy name, which you degraded among the nations where you have gone (Ezek 36:22).

The author of Ephesians expresses this truth more positively:

You are saved by God’s grace because of your faith. This salvation is God’s gift. It’s not something you possessed. It’s not something you did that you can be proud of (Ephesians 2:8-9).

As intriguing as this angle on the paradox is, I must confess that I prefer a different solution. Can God create a rock so heavy that God can’t lift it? Yes. Of course God can. But, God chooses not to, and so remains omnipotent.

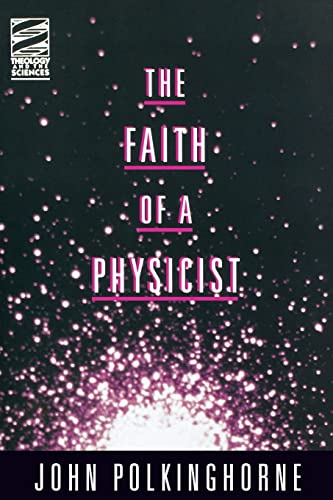

The implications of this seemingly glib solution to the riddle are staggering. God, in God’s freedom, voluntarily chooses to limit Godself! This insight is fundamental to the theology of creation posed by Anglican theologian and particle physicist John Polkinghorne in his 1993 Gifford Lectures. He writes:

The act of creation involves divine acceptance of the risk of the existence of the other, and there is a constant kenosis [literally, an emptying or pouring out] of God’s omnipotence. This curtailment of divine power is, of course, self-limitation on his part, and not through any intrinsic resistance of the creature. It arises from the logic of love, which requires the freedom of the beloved. . . God remains omnipotent in the sense that he can do whatever he wills, but it is not in accordance with his will and nature to insist on total control (The Faith of a Physicist [Minneapolis: Fortress, 1996], 81).

Polkinghorne’s use of the Greek term kenosis immediately brings to mind the Christ hymn quoted by Paul in Philippians 2:6-11:

Though he was in the form of God,

he did not consider being equal with God something to exploit.

But he emptied himself [Greek ekenosen]

by taking the form of a slave

and by becoming like human beings.

When he found himself in the form of a human,

he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death,

even death on a cross.

Therefore, God highly honored him

and gave him a name above all names,

so that at the name of Jesus everyone

in heaven, on earth, and under the earth might bow

and every tongue confess

that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.

That the Incarnation was an act of Divine kenosis is undeniable. Christians confess that, while Jesus was fully God, he was also fully human. But if Polkinghorne is right, God’s emptying of Godself–God’s self-limitation–began not in Bethlehem, or on Calvary, but at the very beginning of all things, when God called into being a world that was not God, and granted to that reality its own authentic autonomy.

Nothing demonstrates this truth so powerfully as what God does on the seventh day:

Thus the heavens and the earth were finished, and all their multitude. And on the seventh day God finished the work that he had done, and he rested on the seventh day from all the work that he had done. So God blessed the seventh day and hallowed it, because on it God rested from all the work that he had done in creation (Gen 2:1-3, NRSV).

God loves and trusts the world that God has made enough to let it go. Of course, this does not mean that God is absent from the cosmos. The God of Genesis is certainly not the clockmaker god of the Deists. Nor, however, is the God we meet in the creation story a divine puppet master, the lone real actor in the cosmic drama. Genesis 2:1-3 affirms that God rests, and the world goes on. Creation is not abandoned by God, and left to its own devices, any more than loving parents abandon their adult children as they prepare to go off on their own. But like a loving parent, God does, in love and confidence, let the world go.