Today, August 18th, marks the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, which gave women the right to vote. It was a victory that had been a long time coming, following decades of protests, civil disobedience, and “unladylike” behavior.

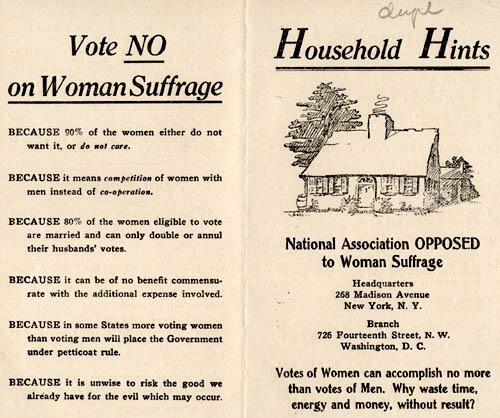

This pamphlet from the time illustrates the attitudes of those opposing the amendment. Inside were household cleaning tips, interspersed with caustic anti-suffrage rhetoric:

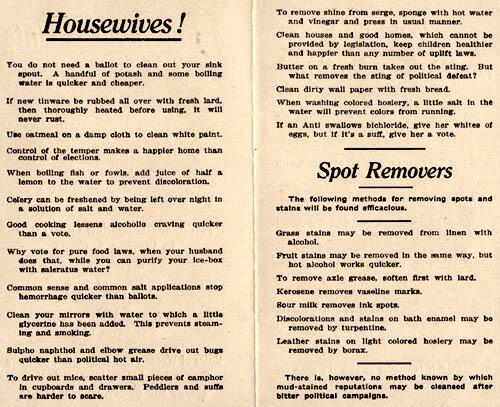

Sadly, the Nineteenth Amendment was not an unalloyed victory: women of color continue to face obstacles to their voting rights a hundred years on. All of which makes Vice-President Joe Biden’s choice of Kamala Harris as his running mate of historic importance.

The nomination of Ms. Harris as a candidate for the vice-presidency has been greeted by sadly predictable questions, concerning her citizenship and her character, that clearly have far more to do with her gender and her race. In an interview with Fox Business network anchor Maria Bartiromo, Mr. Trump said:

“And now, you have — a sort of — a mad woman, I call her, because she was so angry and — such hatred with Justice Kavanaugh,” Trump told Bartiromo. “I mean, I’ve never seen anything like it. She was the angriest of the group and they were all angry. … These are seriously ill people.” He was referring to Harris’ pointed questioning toward Brett Kavanaugh during his 2018 Supreme Court confirmation hearing, after sexual assault allegations from a professor, Christine Blasey Ford, surfaced.

The “mad woman” remarks followed comments Trump made to White House pool reporters the day before. Trump called Harris a “nasty” woman and said she was “probably nastier than even Pocahontas to Joe Biden” during the Democratic debates, referring to Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts.

When then-candidate Trump referred to his opponent Hillary Clinton as a “nasty woman” in 2016, female activists across America took up that insult as a badge of honor, proud to be known as “nasty women”!

This brings us to the Old Testament lesson for this Sunday, Exodus 1:8–2:10! Strong, confident, “nasty women” play an extraordinary, central role in the story of Moses and of Israel’s deliverance. From the midwives Shiphrah and Puah, to Moses’ here-unnamed mother and sister, to the daughter of Pharaoh and her handmaids, women act boldly to undo the hateful plans of Pharaoh, and to carry out the will of God.

Ominously, the passage begins with the emergence of a new pharaoh, “who didn’t know Joseph.” This new monarch not only casts aside the memory of Joseph’s preservation of Egypt in lean times, but actively turns on Joseph’s people:

“The Israelite people are now larger in number and stronger than we are. Come on, let’s be smart and deal with them. Otherwise, they will only grow in number. And if war breaks out, they will join our enemies, fight against us, and then escape from the land.” As a result, the Egyptians put foremen of forced work gangs over the Israelites to harass them with hard work (Exod 1:9-10).

It is important for us to call this what it is. Pharaoh’s fears, and the Egyptians’ dread, were not in any way realistic. There was no indication that the Israelites had any intention to side with Egypt’s enemies in a conflict. The Israelites posed no threat: indeed, Joseph—an Israelite!—had recently been Egypt’s savior (see Genesis 41). But this Pharaoh has no memory: he “did not know Joseph.” His cruelty and oppression toward an ethnic minority in his kingdom responds to an imaginary crisis. This is racism, pure and simple.

On June 17, 2015, Dylann Roof shot and killed nine people [pictured above] attending a Bible study at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, SC. In his statement taken following this horrific crime, Mr. Roof said that he had to do this, in retaliation for black-on-white crime. This is another imaginary crisis, based on fake news from the internet rather than actual crime statistics. Sadly, the escalation of hate crimes in the last four years demonstrates that many others who “feel threatened” by African-Americans, by Latinos and Latinas, by Arabs and Muslims, now feel empowered to express these feelings openly by their words and actions. We must have the courage to call this too what it is: racism pure and simple. We must oppose it wherever we encounter it, and let ethnic and religious minorities know that the church is with them.

Harsh servitude did not succeed in reducing the Hebrew population; indeed, “the more they were oppressed, the more they grew and spread” (Exod 1:12). So Pharaoh decides upon a slow genocide. He enlists Shiphrah and Puah, the Hebrew midwives, in his obscene plot, ordering them to kill every Hebrew boy at birth. The midwives at first agree—but then, they disobey Pharaoh’s command because they “feared God” (Exodus 1:17, NRSV; a better translation of the Hebrew than the CEB “respected God”)–the first mention of God in this book!

Pharaoh of course realizes this—there are still lots of Hebrew boys toddling about, after all—and calls the midwives in to explain themselves. What follows is a masterpiece of subversion. Playing on Pharaoh’s racist beliefs and fears, Shiphrah and Puah tell him a lie he will be likely to believe: the Hebrew women, they say, aren’t delicate and civilized like Egyptian women; they are strong and vigorous, like animals, and give birth before we can arrive! Their plan works.

Pharaoh does not give up on his genocidal designs; ultimately, he will enlist his entire population, ordering all Egyptians to drown Hebrew baby boys (Exodus 1:22). But for a while at least, the courage and ingenuity of Shiphrah and Puah have saved their people. Israel continues to prosper, even in bondage.

As for Shiphrah and Puah, the NRSV reads, “because the midwives feared God, he gave them families” (Exod 1:21). This, however, is far too weak a translation, and the CEB “God gave them households of their own” is only a little better. The Hebrew is wayya’as lahem battim: God “made for them houses”—that is, God established them as clans. This passage claims that there were families in ancient Israel that traced their descent, not from a man, but from a woman: from Shiphrah or Puah.

One of the little boys who lived because of the midwives’ courage was the child of a man and women of the priestly tribe of Levi. Neither is named here (although later, in Exodus 6:20, we learn that they are Amram and Jochebed); nor, as Liddy Barlow observes (“Living By the Word: Reflections on the Lectionary, ” Christian Century 137 [August 12, 2020]: 20), are we told the child’s birth name–although he will come to be called Moses. His birth was a great risk. Pharaoh had sentenced all Hebrew baby boys to death by drowning in the Nile. His parents hide him as long as they can, but when he is three months old, they surrender to the inevitable, and Moses’ mother and sister take him to the river themselves. But instead of drowning the baby, they place him in a tebat (rendered in the CEB as “reed basket”) and set him afloat—hoping against hope that someone will find him and raise him in safety.

The word tebat is not, strictly speaking, a Hebrew word: it is a loanword from the Egyptian tbt, meaning “chest.” It appears in only two places in the Hebrew Bible: twice in Exodus 2: 3, 5 to describe the reed basket in which baby Moses was placed, and 26 times in Genesis 6—8 to describe the boxy structure Noah built. Both Moses’ little tebat and Noah’s enormous tebat are coated inside and out with pitch (Genesis 6:14; Exodus 2:3) in order to make them water-tight. When they read of Moses’ ark, then, careful readers of Scripture recall God’s deliverance of Noah, his family, and the world’s creatures in their ark, and know that as grim as Moses’ future seems at that moment to be, this baby, like Noah, will be saved through water.

After Moses’ mother places her son in his tiny ark, trusting him into the hands of God, Moses’ sister (later we learn that her name is Miriam) follows along on the shore, “to see what would happen to him” (Exodus 2:4). What she sees must have horrified her. In what is surely the worst possible outcome, the little basket floats into the Egyptian princess and her attendants, who are bathing in the Nile.

Remember, Pharaoh himself had commanded that any Egyptian who finds a Hebrew baby boy is to drown the child in the Nile—and surely, if anyone can be expected to obey Pharaoh’s edicts, it is his own daughter! But instead, even though she knows that this child “must be one of the Hebrews’ children” (Exod 2:6), she decides to keep him and raise him as her own—in defiance of her father. It is she who gives him the Egyptian name by which he will be known: Moses. Miriam is then able to step up with an offer to find a Hebrew wet-nurse for the baby: Moses’ own mother. As a result, Moses grows up aware of his heritage. In turn, according to Jewish tradition, Pharaoh’s daughter became known as Bithiah, “daughter of the LORD”; in 1 Chronicles 4:18, we learn that “Bithiah, Pharaoh’s daughter” married into Judah’s line, becoming herself by marriage an Israelite.

Friends, what a story! Praise God, who calls and saves us–and particularly, on this centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, praise God who calls outspoken, courageous, “nasty women” to speak God’s word of grace, love, and justice. My friend and colleague in ministry Liddy Barlow expresses, I am persuaded, the heart of this passage:

Jochebed’s children still make their perilous journeys today, armed with little but their mama’s fierce love. And Bithiahs aplenty sunbathe by the riverside, capable of casual cruelty but also–at our best–able to subvert the systems that sustain us. God calls us into holy conspiracy and invites us into one tangled family, for the sake of the most vulnerable. For God’s own sake.