On Wednesday, June 18, I had ankle replacement surgery. On Monday, July 14, the cast came off. In between, I was largely immobile, spending most of my hours in a recliner with my right leg elevated above my heart. Wendy, Sean and Anthony took extraordinarily good care of me. Still, it was difficult–especially in the early days.

Soon after I returned home from the hospital, I awoke one morning and realized that my leg was itching inside the cast. It was driving me crazy. I twisted my leg inside the cast, got up, stomped around on the walker–and then I realized that I would be trapped in that cast for another three weeks.

I began to have trouble breathing, my heart was racing, I was disoriented–then, I thought, “I am having a panic attack. This must be what a panic attack feels like.” Ice packs on my face and forehead got my breathing and racing heart under control, and I calmed down, but only for a while.

I sat in my chair, trying to think, to pray, to read–trying desperately to think about something, anything, other than my leg. To no avail. Then I thought about my son Sean. Sean has wrestled since childhood with Tourette Syndrome, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, and attendant depression, anxiety, and attention deficit disorder. Along the way, he has learned not only to cope with these conditions, but to thrive. So, when Sean got home from work, I asked him if he could teach me how to fight my obsession with my leg’s discomfort.

Sean’s answer astonished me. He said that he had learned that you can’t fight obsessive thoughts: “They just come.” What you can do is rob those thoughts of the emotions and anxiety associated with them. To do that, Sean taught me, you first relax your body and your mind. Then, you let the forbidden thought come: you deliberately think about what you do not want to think about. As you do so, you keep breathing slowly, you deliberately relax, and so replace the anxiety with calm. Sean suggested that I think, “My leg is uncomfortable, but that really doesn’t matter!”

It worked. That afternoon, when my leg itched, or when I thought about my leg itching or aching, I didn’t fight it. I breathed slowly, in and out, praying the Jesus Prayer in time with my breathing: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, be merciful to me, a sinner.” I thanked God for my healing. I thought about the hundreds of others who had had this surgery, and had come through this period of recovery just fine. I told myself, “My leg is uncomfortable, but that really doesn’t matter.” And I fell asleep–the most restful sleep I had had since coming home from the hospital.

Over the next few days, I continued to practice my prayer and meditation, and bit by bit, my leg stopped bothering me. It didn’t become magically more comfortable, or less prone to itching, but I stopped worrying about it. I “won” when I stopped trying to win–when I stopped fighting.

Since I tend to think biblically–in terms of texts and images from Scripture–this extraordinary experience got me to thinking about martial metaphors in Scripture. Working as I have been recently with the so-called “Minor” Prophets (a far better designation, used by Jewish readers and early Christians, is the Book of the Twelve), I thought of the poems celebrating God as Divine Warrior in Nahum 1:2-11, Habakkuk 3:1-19, and particularly Zechariah 9:13-17. Such images are very old, and very common in Scripture. It is little wonder, perhaps, that our default is to think in terms of combat. Resistance to any evil becomes a war: the War on Drugs, the War on Poverty, the War on Terror. As theologian Walter Wink observed, “Violence is the ethos of our times. It is the spirituality of the modern world.”

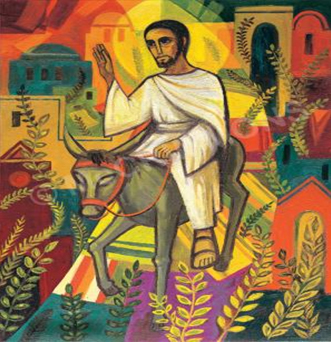

Yet there are other texts in Scripture, which call the martial metaphor into question. One is Zechariah 9:9-12, the only reading from Zechariah in the Revised Common Lectionary. Zechariah 9:9 is quoted in Matthew 21:5 and John 12:15, in their accounts of Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem, and may be assumed in Mark 11:1-11 and Luke 19:28-40 as well (both use the word polon, “colt,” found in the LXX of Zech 9:9):

Rejoice greatly, Daughter Zion.

Sing aloud, Daughter Jerusalem.

Look, your king will come to you.

He is righteous and victorious.

He is humble and riding on an ass,

on a colt, the offspring of a donkey (Zech 9:9).

The Hebrew words translated “righteous and victorious” are tsaddiq wenosha’. The first term means “righteous,” perhaps defending “the royal legitimacy of the king” (see Carol and Eric Meyers, Zechariah 9-14; Anchor Bible 25C [Garden City, N. Y.: Doubleday, 1993], 127), though it may also refer to his morality (the Aramaic translation, or Targum, has zaqay: “innocent”). The second means literally “one who is saved,” though most English translations (including the CEB) follow the Greek LXX, which renders this as sozon, meaning “one who saves.” Carol and Eric Meyers, however, stay with the plain sense of the Hebrew: God, they say, is the one who “is victorious over the enemies, with the result that the king is ‘saved,’ thereby enabled to assume power” (Meyers and Meyers 1993, 127). This is a very different idea of kingship, grounded not in the king’s victories in battle, but in God’s own action (compare Zech 4:6).

The distinctions between this king and other, previous kings continue to be drawn as this passage continues. Although the humble mount in Zechariah 9:9 derives from a long tradition in the ancient Middle East of kingly processions where the king rode an ass (Meyers and Meyers 1993, 129), this passage surely catches the point of that tradition: by riding an ass rather than a war horse or chariot, the king shows humility, and declares that he comes in peace.

Yet this time, the prophet declares, this is no pretense: this king truly is humble, and not only comes in peace, but comes to bring peace:

He will cut off the chariot from Ephraim

and the warhorse from Jerusalem.

The bow used in battle will be cut off;

he will speak peace to the nations.

His rule will stretch from sea to sea,

and from the river to the ends of the earth (9:10).

Another surprising passage is Zechariah 14:13-19, which at first seems to be yet another depiction of God as warrior, and of God’s victory as accomplished through violent struggle. In the last day, this vision declares, Jerusalem’s people will plunder those who had come to plunder them (a common biblical theme; see Exod 12:33-36; Ezek 39:9-10; 2 Chr 20:25). So that the enemy will never again be able to mount an attack on Jerusalem, a plague will strike “the horses, mules, camels, donkeys, and any cattle in those camps” (Zech 14:15), destroying their military capability entirely.

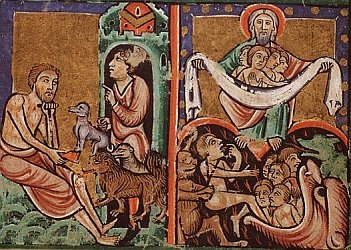

Yet despite the sweeping devastation of plague and war, the enemies of Jerusalem are not utterly destroyed: “All those left from all the nations who attacked Jerusalem will go up annually to pay homage to the king, the Lord of heavenly forces, and to celebrate the Festival of Booths” (Zech 14:16).

Similarly in the book of Revelation, even after the last judgment sees all the enemies of God’s people (including “Death and the Grave”) thrown into the lake of fire (Rev 20:11-15), John can still somehow say of the New Jerusalem, “The nations will walk by its light, and the kings of the earth will bring their glory into it. Its gates will never be shut by day, and there will be no night there. They will bring the glory and honor of the nations into it” (Rev 21:24-26). God’s ultimate purpose is not destruction after all, but transformation and renewal.

In Zechariah 14:6, the nations do not necessarily come to Jerusalem willingly—their participation, and particularly the participation of Egypt (Zech 14:18-19; for Egypt as a symbol of foreign oppression, see Hos 11:5; Zech 10:10-11), is coerced by the threat of plague! Still come they do, every year, at Sukkot, the Festival of Booths.

This autumn pilgrim feast, the most important of the festivals according to many biblical traditions (for example, 1 Kgs 8:2; Isa 30:29; Ezek 45:25; Neh 8:14; John 7:2, which refer the Sukkot as “the festival”), is an appropriate time for the nations to observe fealty to the Lord, as it is also the time set for the reading and remembrance of the Law of Moses (Deut 31:10-11; Neh 8:13-18). The nations join the faithful of Israel in proclaiming fealty to the Lord, and faithfulness to God’s commandments.

Reading these passages, I find myself thinking of Abraham Lincoln’s response to a fiery old woman, who took issue with him for speaking of Southerners as people in error, rather than enemies to be destroyed: “Why, madam, do I not destroy my enemies when I make them my friends?”

Without doubt, the imagery of warfare and struggle is part of the biblical witness. But Scripture also, in many places, subverts that imagery, transforming it unexpectedly into imagery of peace. What would happen if we listened to those texts, rather than focusing on the others? How might that change the way we confront our struggles, whether internal, interpersonal, or international? What might happen if we stopped fighting, let our anger, fear, and anxiety go, and opened ourselves to God’s peace?

AFTERWORD:

Thank you for your thoughts and prayers! I am well on the way to wholeness, but I appreciate your continued prayers as I move into the next phase of my recovery.

In “Princess Bride,” one of my favorite films, a continuing shtick involves Wallace Shawn’s character, Vazzini, who uses the word “

In “Princess Bride,” one of my favorite films, a continuing shtick involves Wallace Shawn’s character, Vazzini, who uses the word “ In

In