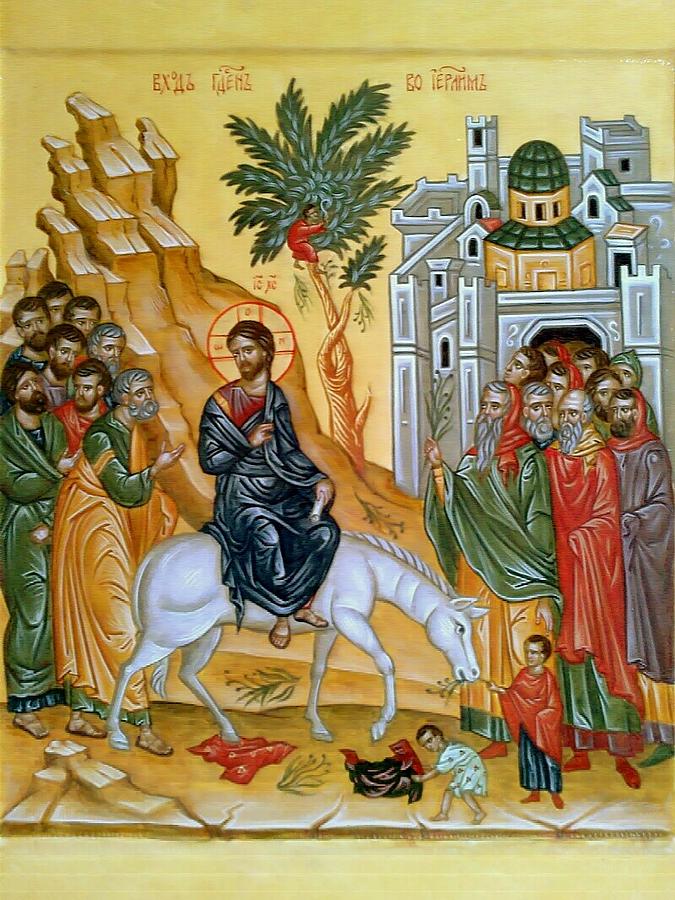

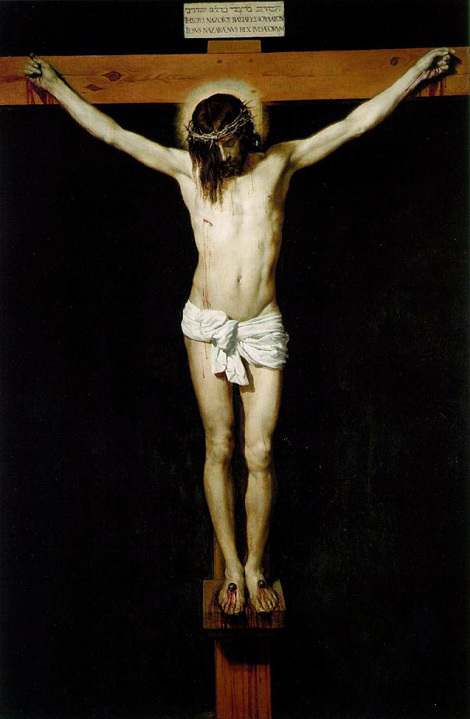

This Sunday, Palm or Passion Sunday, marks the beginning of Holy Week, leading up to the remembrance of Jesus’ death on the cross–and of course, ultimately, to the celebration of his resurrection, and our own. We Christians may think that now of all times our proclamation must stick to the uniquely Christian Scriptures on the right-hand side of our Bibles. But in truth, we cannot understand the Gospel account for this day without looking at three passages in particular from the Hebrew Bible.

Curiously, Zechariah 9:9-12 is not one of the lectionary readings for Palm Sunday in any year, although Matthew and John both quote Zechariah 9:9 in their accounts of Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem (Matt 21:5 and John 12:15; see also Mark 11:1-11 and the Gospel reading for this year’s celebration, Luke 19:28-40, which both use the word polon, “colt,” found in the Septuagint’s Greek translation of Zech 9:9):

Rejoice greatly, Daughter Zion.

Sing aloud, Daughter Jerusalem.

Look, your king will come to you.

He is righteous and victorious.

He is humble and riding on an ass,

on a colt, the offspring of a donkey.

Applying to this passage a deliberately wooden literalism, Matthew describes Jesus entering Jerusalem somehow mounted on both an ass and her colt (Matt 21:6-7)! This bizarre image was doubtless intended to ram the point home, making absolutely certain that the reader could not miss the connection between Jesus’ actions and the prophet’s words. As the early Christian teacher Theodoret of Cyrus records, “This acquires a clear interpretation in actual events: the king who is prophesied has come” (Commentary on the Twelve Prophets, trans. Robert Charles Hill [Brookline: Holy Cross, 2006], 256).

The CEB translation “righteous and victorious” (9:9) is difficult to understand. The Hebrew reads tsaddiq wenosha’. The first term means “righteous,” perhaps defending “the royal legitimacy of the king” (so Carol and Eric Meyers, Zechariah 9-14; AB 25c [Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1993], 127; note that NRSV has “triumphant”), although it may also refer to his morality (the Aramaic Targum Nebi’im has zaqay, meaning “innocent”). The second term is a passive participle meaning literally “one who is saved” (reflected also in the Aramaic of Tg. Neb.). The Septuagint renders this as sozon, an active participle (“saving”). David Petersen, who translates these two words as “Righteous and victorious,” says that the Greek reading “seems to be the required sense” (Zechariah 9—14 and Malachi, OTL [Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1995], 55). Carol and Eric Meyers, however, stay with the plain sense of the Hebrew: “[The LORD] is victorious over the enemies, with the result that the king is ‘saved,’ thereby enabled to assume power” (Meyers and Meyers 1993, 127). In short, this is already a transformed notion of kingship, grounded not in dynastic and regal pomp and power, but in God’s own salvation and deliverance.

As this passage unfolds, it continues to draw distinctions between this king and other, previous kings. The humble mount in Zech 9:9 derives from a long tradition of kingly processions (Meyers and Meyers 1993, 129). By riding an ass rather than a war horse or chariot, the king shows humility and declares that he comes in peace. But this time, the prophet declares, this is not just for show! This king truly is humble, and not only comes in peace but also comes to bring peace:

He will cut off the chariot from Ephraim

and the warhorse from Jerusalem.

The bow used in battle will be cut off;

he will speak peace to the nations.

His rule will stretch from sea to sea,

and from the river to the ends of the earth (Zech 9:10).

In the Persian period, the province (called a “satrapy”) to which Judah belonged was Abar-Nahara: that is, the lands “Beyond the River,” across the Euphrates and west toward the Mediterranean Sea. “[F]rom the river to the ends of the earth” seems to envision Jerusalem’s sway extended throughout this region. Further, the mention of Ephraim (the largest of the northern tribes, often used to represent the entire northern kingdom of Israel, e.g., Isa 7:2; Jer 7:15; Ezek 37:19; Hos 5:3) shows that this renewed kingdom will include those formerly excluded, the “lost tribes” from the northern kingdom destroyed and dispersed by the Assyrians long before.

It is little wonder that this passage, with its transformed view of kingship, so captured the imagination of the Gospel writers. While the first Christians confessed Jesus as christos, the term used in the Septuagint for Hebrew meshiakh (“Messiah”), it is clear that their understanding (and Jesus’ own understanding) of what it meant to be “Messiah” transformed that image. Mark 1:1 identifies Jesus not only as Christos, or Messiah, but also as “the Son of God.” While related to the idea of the king as God’s adopted son (Pss 2; 45), this confession goes much further than any Jewish conception of Messiah: Jesus the Messiah is God! This confession creates new problems, raising the need for the church to affirm that “Jesus Christ has come as a human” (1 John 4:2; see also John 1:14).

But while Christian confessions about Jesus exalt the role of Messiah far beyond traditional Jewish expectations, they at the same time subvert the idea of Messiah as king. In debate with the Pharisees, who believed in a literal future Messiah (Matt 22:41-46), Jesus asks,

“What do you think about the Christ? Whose son is he?” “David’s son,” they replied (Matt 22:42).

In response, Jesus quotes Psalm 110:1:

The Lord said to my lord, ‘Sit at my right side until I turn your enemies into your footstool’

Assuming the speaker to be David (the title of this psalm after all identifies it as a psalm of David), Jesus asks, “If David calls him [that is, the Messiah] Lord, how can he be David’s son?” (Matt 22:45). Although Matthew’s genealogy takes pains to demonstrate Jesus’ descent from David (Matt 1:6, 17), Christ is more than another Davidic king!

Particularly subversive of traditional Messianic expectation is the Christian view that the Christ must be understood in terms of suffering. Thus, in Mark, Peter’s confession at Caesarea Philippi that Jesus is the Christ is inadequate: faced with Jesus’ determination to suffer and die, Peter rebukes him and is in turn himself rebuked by Jesus (Mark 8:29-33). Indeed, in Mark, the first human to make a full confession about Jesus is his executioner, who declares when Jesus dies, “This man was certainly God’s Son” (Mark 15:39). It may well be that Jesus understood his own role in terms of the Servant of the LORD in Second Isaiah (Isaiah 42:1-9; 49:1-7; 50:4-11; and 52:13—53:12). Certainly, early Christians did (see 1 Cor 15:3; Acts 8:32-35; 1 Peter 2:22-25), and the idea must have come from somewhere (cf. Matt 8:17; 12:18-21; 20:28; Mark 9:12; 10:45; Luke 22:37). In any case, for early Christians, the image of the peaceful and humble king in Zechariah 9:9-10 was the perfect representation of Jesus.

The gospel lesson for Palm Sunday this year is missing one familiar feature: in Luke’s account of Jesus’ triumphal entry, nothing is said of the crowd shouting “Hosanna!” This is typical of Luke–writing as a Gentile for a Gentile audience, he often avoids Jewish or Semitic elements (which is why Luke 23:33 uses the Greek Kranion [“The Skull”] rather than the Aramaic Golgotha for the place where Jesus is crucified; the KJV of Luke 23:33 uses the Latin Calvary; both “Calvary” and “Golgotha” also mean “skull”). Still, “Hosanna!” is woven into our Palm Sunday hymns, and into our liturgies. In Matthew, Mark, and John’s accounts, the crowds shout “Hosanna!” the way that we might cheer at a ball game:

Those in front of him and those following were shouting, “Hosanna! Blessings on the one who comes in the name of the Lord! Blessings on the coming kingdom of our ancestor David! Hosanna in the highest!” (Mark 11:9-10; compare Matthew 21:9; John 12:13).

“Hosanna” comes from Psalm 118, the Psalm reading for this Sunday. Psalm 118:25 reads in Hebrew:

‘ana’ YHWH hoshi’ah na’

‘ana’ YHWH hatslikhah na’.

In Judaism, this Psalm is part of the Hallel (Pss 113—118), sung in festivals and particularly at Pesach, or Passover: the feast that in today’s reading brought these crowds on pilgrimage from across the Roman world to Jerusalem. The first two psalms in the Hallel are sung before the Passover meal, and the last four are sung after. So the Hallel would have been in the air, for any Jewish community, surrounding Pesach. Little wonder the words of the Hallel come so readily to the lips of the crowd.

The Hallel would have been learned, and sung, in Hebrew, but most ordinary Judeans in Jesus’ day didn’t actually speak Hebrew: their everyday language would have been Aramaic. So, while the crowds know the words to the song, they don’t necessarily know what those words mean. While they shout “Hosannah!” as though it meant “Hurray!,” what it really means is “Save us, please!” The CEB translates this verse,

Lord, please save us!

Lord, please let us succeed!

Whether the crowd knows it or not, when they shout “Hosannah!,” they are calling for Jesus to save them!

The last passage presupposed by our Palm Sunday Gospel reading is Habakkuk 2:9-11:

Doom to the one making evil gain for his own house,

for putting his own nest up high,

for delivering himself from the grasp of calamity.

You plan shame for your own house,

cutting off many peoples

and sinning against your own life.

A stone will cry out from a village wall,

and a tree branch will respond.

The expression botsea’ betsa’ (“making. . . gain”) elsewhere refers to greedy, unjust gain (Prov 1:19; 15:27), and particularly to the wealthy and powerful preying on the poor and powerless (Jer 6:13; 8:10; Ezek 22:27). But Habakkuk doubles down on this depiction by adding the adjective ra’ (“wicked, evil”): “Doom to the one making evil gain for his own house” (2:9). Often in Hebrew, “house” refers to one’s family, but here the term is used literally to refer to the solid, secure mansions of the rich (see also Amos 5:11; Isa 5:9). In the following verses, Habakkuk plays with this ambiguity, going back and forth between house as a building, and house as one’s family.

Habakkuk accuses the rich of using their unjust gains for

for putting his own nest up high,

for delivering himself from the grasp of calamity (2:9).

The reference to a nest set “up high” calls to mind the eagle’s nest (Job 39:27) used as a metaphor for security. Indeed, the Song of Moses (Deut 32:1-43) compares God’s providential care and protection of Israel in the wilderness to the eagle nurturing its young in their nest:

Like an eagle protecting its nest,

hovering over its young,

God spread out his wings, took hold of Israel,

carried him on his back (Deut 32:11).

Elsewhere, however, this metaphor depicts a vain quest for safety; those who seek, like the eagle, to set their nest high in the rocks will be brought down (Num 24:21-22; Jer 49:16; Obad 3-4).

So, Habakkuk declares, robbing the poor to set up strong and secure houses will bring the wealthy of Jerusalem no security. Instead of gaining security, by the pursuit of dishonest gain, “You plan shame for your own house”–here, the family rather than the physical structure–and indeed are “sinning against your [the NRSV has “you have forfeited”] your own life” (2:10).

The CEB of Hab 2:11 reads, “A stone will cry out from a village wall, and a tree branch will respond.” The NRSV reads, “The very stones will cry out from the wall, and the plaster will respond from the woodwork.” The word rendered “tree branch” in the CEB and “plaster” in the NRSV is the Hebrew kaphis, found only here in the Hebrew Bible. From its use elsewhere, however, it seems best to render it as “beam” or “rafter” (see the KJV and NIV of this passage). In short, the houses themselves (here, the buildings once more) will witness against their wicked owners!

In Luke’s account of the triumphal entry into Jerusalem, Jesus alludes to Habakkuk 2:11. When the Pharisees’ demand that Jesus silence his obstreperous followers, Jesus says, “I tell you that, if these should hold their peace, the stones would immediately cry out” (Luke 19:40). Jesus, like the prophet Habakkuk, opposes the religious and secular leadership of Judah for refusing to hear the outcry of the poor–something we might miss entirely if we didn’t know where Jesus’ words were coming from!

Brothers, sisters, friends, as you worship and teach and preach this week, let your proclamation be enriched by the whole of Scripture! God be with you.