This Sunday’s epistle, 1 Corinthians 8:1-13, is one of my favorite passages from Paul’s letters. That may strike you as odd: why should I be so enamored of this weird passage, on such an obscure matter? But friends, I am persuaded that Paul’s treatment of the question of whether or not Christians may eat food offered to idols has a significance far beyond its narrow cultural and historical context. Bear with me for awhile.

To us, of course, this question is irrelevant. Whether or not we should eat food offered to idols isn’t even on our radar screen! But we know from our New Testament that this issue divided the early church. In Acts 15, the Apostolic Council–called to consider whether Gentiles could be part of the body of Christ–turned, in part, on this divisive issue. James, leader of the Jewish Christians in Jerusalem (and likely, the brother of Jesus and the source of the Christian wisdom recorded in our book of James) spoke for the Council:

I have reached the decision that we should not trouble those Gentiles who are turning to God, but we should write to them to abstain only from things polluted by idols and from fornication and from whatever has been strangled and from blood (Acts 15:19-20, NRSV).

Gentiles would not need to become Jews in order to be followers of Christ. However, all believers, Jew and Gentile alike, had to follow some rules. They had to abide by a bare minimum of kosher law (no eating blood, or meat with the blood still in it: that is, from animals killed by strangling). They had to forswear the sexual perversions that James believed (with some justification!) were rife in the Greco-Roman world. But at the top of the list, they had to abstain “from things polluted by idols”–that is, no eating food that had been offered as a sacrifice. The John of Revelation too held that those who ate food sacrificed to idols separated themselves from the church of Jesus Christ (Rev 2:14, 20).

We may think that, even in the ancient world, this surely could not have been that big a deal: how hard would it have been to avoid eating food offered to an idol? As it turns out, it could be very difficult indeed! Temples, and their priesthoods, supported themselves largely through sacrifices. A select portion of the worshipper’s offering would be burned on an altar for the god. But the remainder became the property of the temple, and of the priestess or priest. They could sell it to vendors, to be resold on the open market to consumers. So, unless you were very careful about where you obtained your meat, you might not know whether it had first been offered to a god or goddess.

We may think that, even in the ancient world, this surely could not have been that big a deal: how hard would it have been to avoid eating food offered to an idol? As it turns out, it could be very difficult indeed! Temples, and their priesthoods, supported themselves largely through sacrifices. A select portion of the worshipper’s offering would be burned on an altar for the god. But the remainder became the property of the temple, and of the priestess or priest. They could sell it to vendors, to be resold on the open market to consumers. So, unless you were very careful about where you obtained your meat, you might not know whether it had first been offered to a god or goddess.

If you took avoiding such food seriously, you would also be very careful about with whom you socialized. You couldn’t eat with nonbelievers–or even with other believers who weren’t as scrupulous as you were. Indeed, as the texts from Revelation cited above showed, you might even deny that those less careful Christians were Christians at all.

Avoiding meat offered to idols could have economic implications as well. Practitioners of skilled trades were organized into guilds, which could be dedicated to a patron god or goddess–like the silversmiths of Ephesus, dedicated to Artemis (Acts 19:23-41; the Romans called this goddess Diana). Guild gatherings would have involved meals, likely including food offered to their divine patron. To avoid eating such food, Christians (for example, Christian silversmiths in Ephesus) would have to surrender their guild membership–but if they did that, they would likely find employment difficult or impossible. Abstaining from food offered to idols could mean losing their livelihood.

However, as Paul’s letter to the Corinthian Christians shows, some believers thought differently. They reasoned that, since there was only one true God, idols were merely statues, and food sacrificed to them was no different than any other kind of food (see 1 Cor 8:1-6). Paul, who steadfastly refused to reduce faith to rule-following, certainly agreed with their theology:

There is one God the Father.

All things come from him, and we belong to him.

And there is one Lord Jesus Christ.

All things exist through him, and we live through him (1 Cor 8:6).

But Paul refused to settle the matter legalistically, either way–because Paul understood that the food itself was not the real issue. What really mattered was sensitivity to one another in the body of Christ. If the faith of “weaker” Christians is threatened when they see other believers eating food sacrificed to idols, then the “stronger” Christians need to abstain (1 Cor 8:7-13).

This does not mean, by the way, that Paul simply surrendered to the rule-followers! In Galatians 2:11-14, when Peter refuses to eat with Paul’s Gentile converts for fear of James’ “circumcision faction” (Gal 2:12, NRSV), Paul is caustically scornful:

But when I saw that they weren’t acting consistently with the truth of the gospel, I said to Cephas [Peter’s name in Aramaic] in front of everyone, “If you, though you’re a Jew, live like a Gentile and not like a Jew, how can you require the Gentiles to live like Jews?” (Gal 2:14).

Paul sums up his advice on food sacrificed to idols in 1 Corinthians 10:23-33. Buy your meat wherever is convenient, and eat it without fear. Accept invitations from unbelievers–after all, how will you ever have the opportunity to witness for Christ if you only associate with like-minded Christians? Thank God for whatever they offer you, and eat it gratefully–unless they make an issue of it, by telling you that the food you are eating comes from an idol sacrifice. But even then, notice, the issue is not the food or where it comes from, but the conscience of the person who has offered this food to you, who may think that, by knowingly eating food offered to an idol, you are condoning their idolatry.

So, whether you eat or drink or whatever you do, you should do it all for God’s glory. Don’t offend either Jews or Greeks, or God’s church. This is the same thing that I do. I please everyone in everything I do. I don’t look out for my own advantage, but I look out for many people so that they can be saved (1 Cor 10:31-33).

For Paul, people, and their salvation, matter more than ideology, or even than right theology.

![First and Second Chronicles: Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching by [Steven S. Tuell]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61IXNLlCesL.jpg)

Paul’s resolution of this thorny problem reminds me of another favorite passage, from the left-hand side of the Bible (2 Chronicles 30:15-22). King Hezekiah had invited refugees from the northern kingdom of Israel, who had escaped the fall of their kingdom to Assyria (722 BCE), to come to Jerusalem for Passover. Sadly, Hezekiah’s invitation was rejected by many in the north, who laughed at and scorned his messengers (2 Chr 30:10). Perhaps Jesus was thinking of this passage when he told his parable of the wedding feast (Matt 22:1-14; compare Lk 14:15-20), where the messengers are also scorned and ill-treated.

However, as in Jesus’ parable, the failure of those invited to respond does not stop the feast! Some northerners, from the tribes of Asher, Manasseh, and Zebulun, do humble themselves (an important theme in Chronicles; see 2 Chr 7:14) and come south to Jerusalem for the feast. In Judah, meanwhile, the response is overwhelming: “God’s power was at work in Judah, unifying them to do what the king and his officials had ordered by the Lord’s command” (2 Chr 30:12). The Hebrew of this verse says that God gave them leb ‘ekhad–that is, “one heart” (see 1 Chr 12:38, where those who come to make David king are likewise said to be of “one heart”). In the end, “a huge crowd” gathers in Jerusalem for the feast (2 Chr 30:13). Jerusalem and the temple are cleansed, and the priests and Levites stand ready to serve (2 Chr 30:15), conducting themselves “according to the law of Moses the man of God” (2 Chr 30:16, NRSV).

It is fortunate that the priests and Levites are ready, for a great number of those attending are ritually unclean, and so cannot kill their own sacrifices; the Levites must do this for them (2 Chr 30:17; for the killing of the sacrifice by Levites, see also Ezr 6:20; Ezek 44:11). Nothing is said of the reasons for their defilement; however, since many of those said to be defiled come from the north (2 Chr 30:18), they may have had different ideas about what constitutes ritual purity, or about the requirements for the observance of Passover. From the Chronicler’s perspective, however, this means that they “hadn’t eaten the Passover meal in the prescribed way” (2 Chr 30:18)–that is, they were in violation of God’s law in Scripture (see 2 Chr 30:5).

But rather than barring these rule-breakers from his Passover, Hezekiah prays for them:

May the good LORD forgive everyone who has decided to seek the true God, the LORD, the God of their ancestors, even though they aren’t ceremonially clean by sanctuary standards (2 Chr 30:18-19).

The LORD hears the king’s prayer, and the community is healed (2 Chr 30:20; compare 2 Chr 7:14).

Hezekiah’s prayer, and the LORD’s favorable response, strike a blow against legalism. Clearly, it is more important to set one’s heart to seek God than it is to be in a state of scrupulous ritual purity. Similarly, the prophet Micah declares:

He has told you, human one, what is good and

what the Lord requires from you:

to do justice, embrace faithful love, and walk humbly with your God (Mic 6:8).

In his teaching, Jesus as well placed “the more important matters of the Law: justice, peace, and faith” above laws of ritual purity (Matt 23:23). So, for Jesus, meeting human need by healing on the sabbath was more important than strict adherence to the regulations of the rabbis (so, for example, Mk 3:1-6).

Today, the church is divided by other questions and controversies. Yet, we still are tempted to appeal to legalism, whether in our reading of Scripture or in our application of community standards–which, far from resolving our conflicts, only heightens our division. We need to remember that Scripture itself rejects this narrow, rigid standard. How much better, like Paul and King Hezekiah, to put people before ideology: to trust in God’s grace, and remember that devotion to the Lord, and loving those whom God loves, is our first and highest calling.

AFTERWORD:

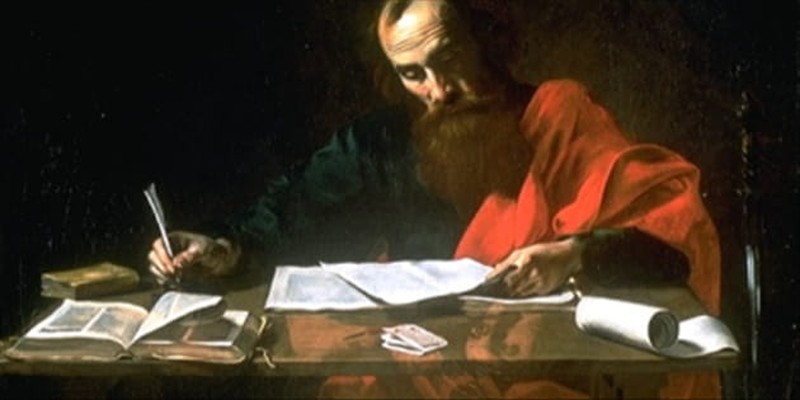

The image of Roman sacrificial religion above comes from Wikipedia: Emperor Marcus Aurelius (161-180 AD) and members of the Imperial family offer[ing] sacrifice in gratitude for success against Germanic tribes. In the backgrounds stands the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitolium (this is the only extant portrayal of this [R]oman temple).”