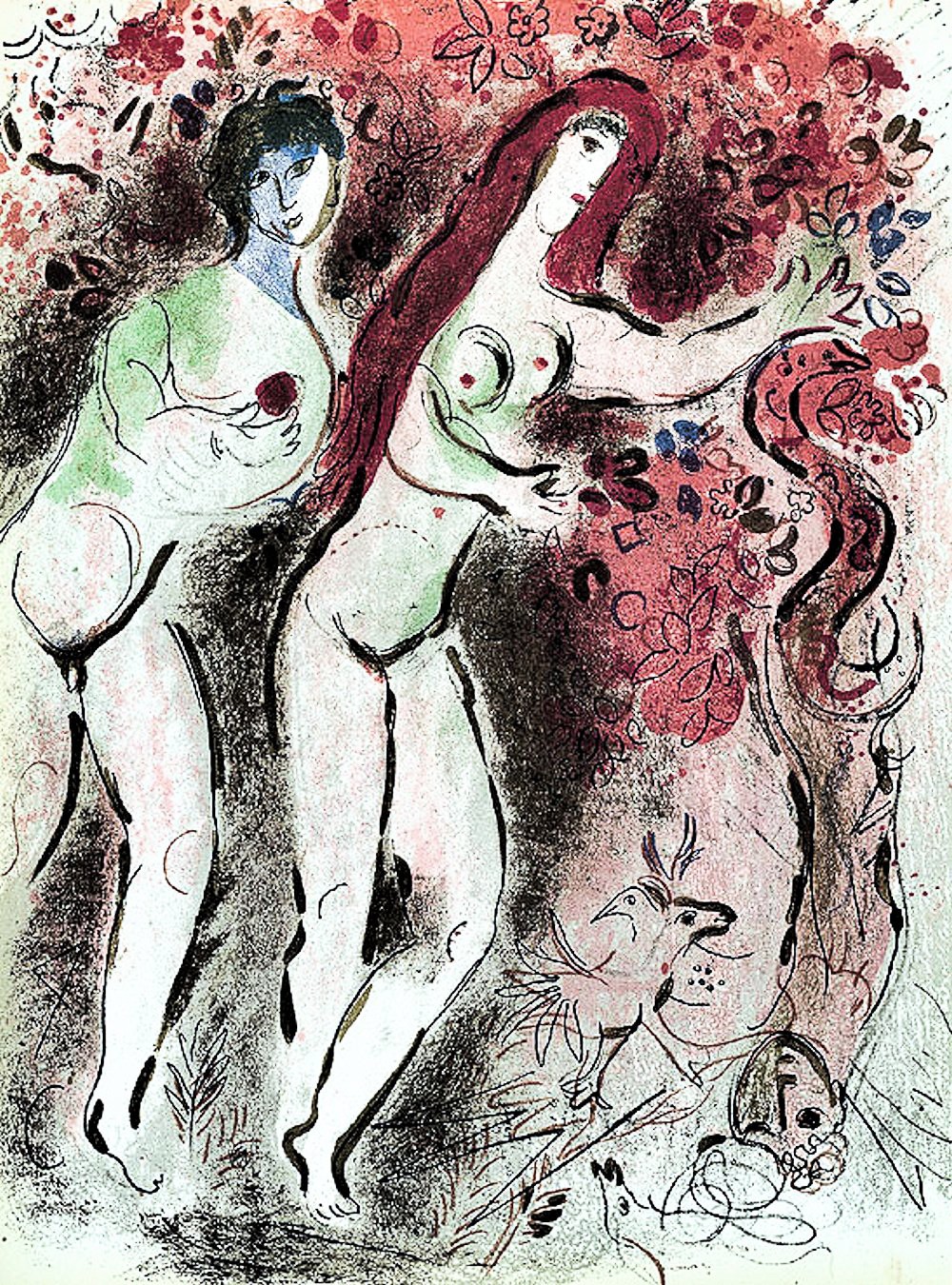

Close readers of Scripture recognized early on that God creates woman twice in the opening chapters of Genesis. The first creation of woman is described in Genesis 1:27 (CEB):

God created humanity [Hebrew ‘adam] in God’s own image,

in the divine image God created them,

male and female God created them.

The second account of the creation of woman is the familiar story of Eve in Genesis 2:21-23, where God causes a deep sleep to come upon Adam, performs major surgery, crafts the woman from the man’s flesh, and brings her to him.

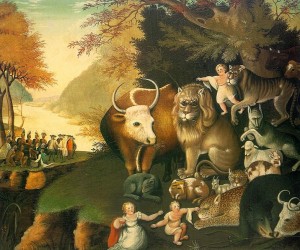

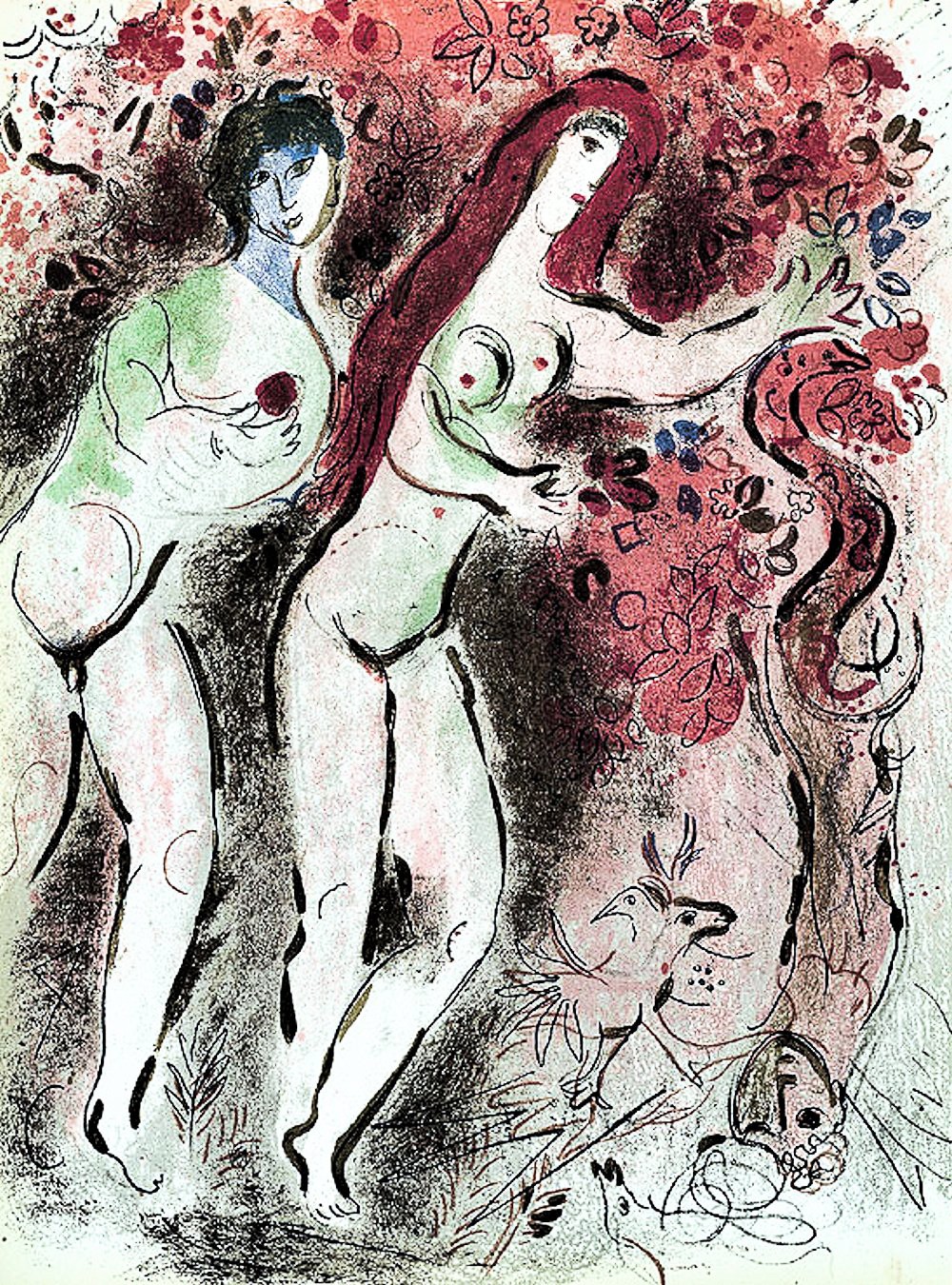

Traditional Jewish interpreters made sense of this tension by proposing that God created not one but two wives for Adam. According to Jewish legend, the first wife, whose creation is described in Genesis 1, was called Lilith.

The legend says that Lilith was beautiful, but willful and vain, refusing to submit to the authority either of God or of Adam. So, she was booted out of the garden.

God then created Eve: a second, presumably more pliant wife, made from Adam’s own stuff – hence, the story of the creation of woman in Genesis 2. As for Lilith, she became a creature of the night: a seductress who tempts holy men in their dreams and gives birth to demons and monsters.

Though the story of Lilith is of course a legend, it points us to the tension within these chapters: clearly, something odd is going on in the opening pages of Genesis!

Genesis 1 begins, “When God began to create the heavens and the earth— the earth was without shape or form, it was dark over the deep sea, and God’s wind swept over the waters” (Gen 1:1-2). The phrase “the heavens and the earth” is repeated in Genesis 2:4a, in what sounds like a summary statement: “This is the account of the heavens and the earth when they were created.” Immediately after this apparent summary, we read, “On the day the LORD God made earth and sky . . .” (Gen 2:4b)—the same expression, but flipped on its head. Another account of beginnings appears to follow (Gen 2:4b-25).

Is it possible, then, that in the first two chapters of Genesis we have two distinct accounts of creation, one in Genesis 1:1 – 2:4a and a second in Genesis 2:4b—25? For millennia, we have read the text as though Genesis presented us with a single account of beginnings: one creation story. But could it be that we have not one creation story, but two?

We can assess this idea, and explore how these texts relate to one another, by posing to these two passages a series of questions.

First, How is the Divine addressed in each passage? In the English translation of Genesis 1:1 – 2:4a, the creator is called simply “God.”

The Hebrew word is ‘elohim, which literally means “gods.” In Hebrew, however, the plural can be a way of indicating majesty. So, while ‘elohim does mean “gods” sometimes, it is commonly used as shorthand for “God of gods” or “God above all gods.” In Genesis 1:1 – 2:4a, this is consistently the way the divine creator is addressed.

But in Genesis 2:4b—25, we find not only “God” (again, ‘elohim), but also the expression “LORD,” in all capitals. That is the way that most English translations represent the personal Name of God, YHWH.

Like the repetition of “the heavens and the earth” bracketing 1:1—2:4a, the two different names used for the Divine in our passages are suggestive. But we can push further to ask about the “stuff” of creation: What does the Creator make things out of?

This may seem an odd question. Haven’t we been taught that God creates out of nothing? Later Jewish and Christian theologians and philosophers talk about creation in this way because of their high view of God. If God is indeed God, then God is not an object in the world of time and space: certainly, then, God must have called all that is into being. Therefore, Jewish, Christian, and Muslim theologians alike talk about Creatio ex nihilo: that is, God creating the world “out of nothing.”

However, that is not what Genesis 1—2 is about. The question posed by these chapters is not, “Where did the world come from?” Ancient people really did not care how the world began.

What they wanted, and needed, to know was something more immediate and pressing: is there a meaningful order to reality? Can I plant my crops and know that the rain will fall, the sun will rise, the seed will sprout and germinate, and the harvest will come?

Ancient people knew all about solstices and equinoxes. Though they did not understand how this happened, they were fully aware that every year, when the autumnal equinox rolls around, the day and the night are of equal length (hence, “equinox:” that is, “equal night”). But every night after that the nights get longer and longer, and every day after that the days get shorter and shorter, until finally we come to the winter solstice: the longest night and shortest day of the year.

Every human culture in the world recognizes the equinoxes and the solstices, and for a very important reason. After all, how can we know that this time around, the nights won’t just keep getting longer and longer and longer until everything is swallowed up in night? How can we know that this time around the air won’t just continue to get colder and colder and colder until everything is swallowed up in an endless winter of darkness and death?

Can we be certain that the wheel will turn and that the cycle will continue? In short: does the world make sense?

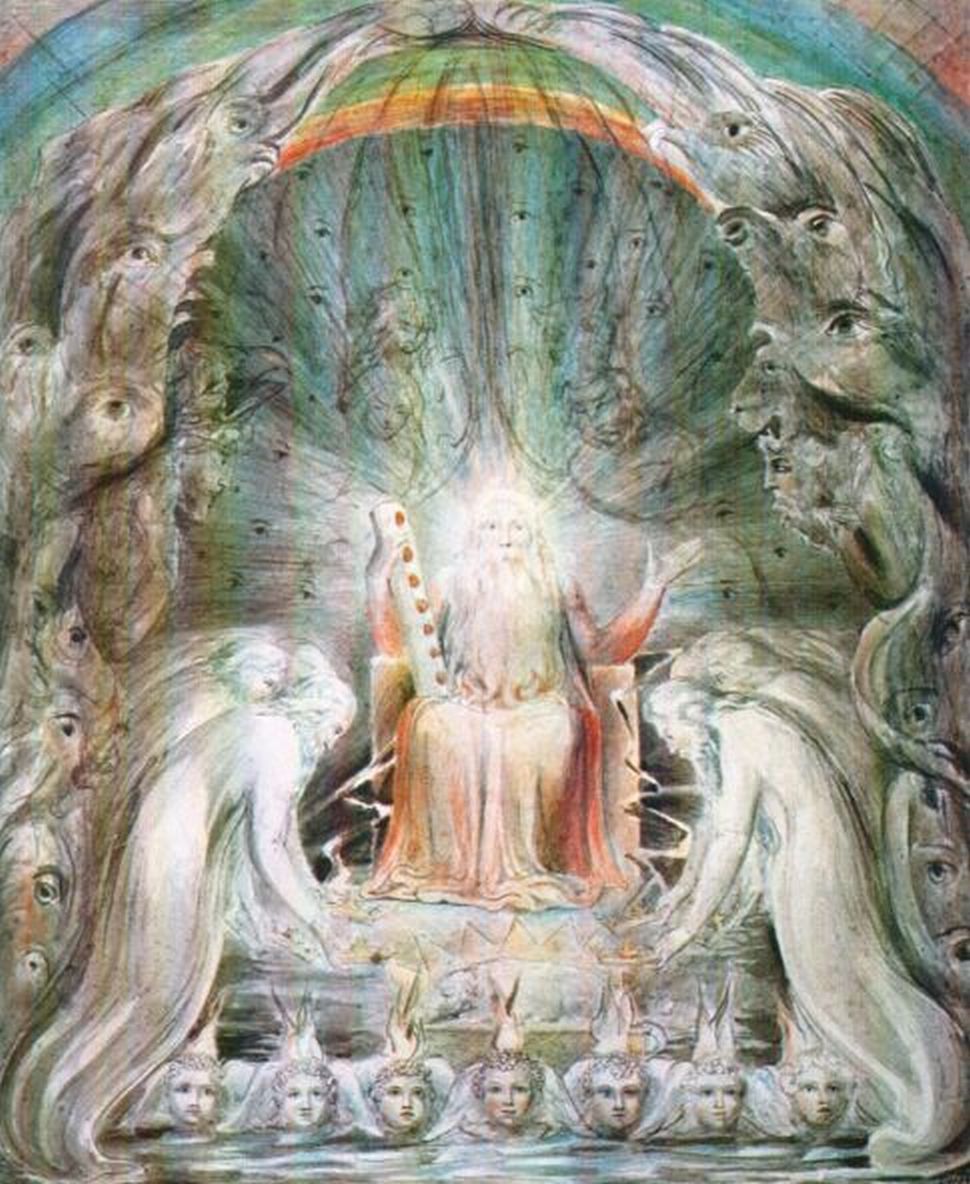

The opening verses of Genesis record, ““When God began to create the heavens and the earth— the earth was without shape or form” (Hebrew tohu wabohu; Gen 1:1-2). This “formless void” (the NRSV rendering of the verse) is further described as “the deep sea” (Hebrew tehom) and “the waters” (Hebrew hammayim; Gen 1:2). In Genesis 1:1-2, then, the state of things when God began creating was chaos, without order or pattern, represented as tossing, shifting, formless water.

Picture yourself floating in the ocean. There is no land in sight. It is night: the sky is overcast, so that there is no moon and no starlight. All you can see, all you can imagine, is the endless rise and fall of the water, the tossing of the waves, and the wind blowing over the deep. That is the way Israel’s ancient priests imagined the beginning of things.

It all begins with shapeless, formless water. But God imposes order on that chaos. The implicit question in Genesis 1, then, is not, how did the world begin, but rather, does the world make sense? God establishes order and meaning in place of disorder and meaninglessness.

When we turn to Genesis 2, we find a different image. Here the heavens and the earth are presupposed; God has already created them, offstage. This account begins, “On the day the LORD God made earth and sky—before any wild plants appeared on the earth, and before any field crops grew, because the LORD God hadn’t yet sent rain on the earth and there was still no human being to farm the fertile land. . .” (Gen 2:4b-5). Here, the earth is like a dry field, with nothing growing and no rain.

But God permits water to bubble up from beneath the earth, and moisten the surface of the ground (Gen 2:6). What happens next is the chemical reaction that every two year old learns: water plus dirt equals mud.

Out of the mud, the LORD begins to create: “the LORD God formed the human from the topsoil of the fertile land and blew life’s breath into his nostrils. The human came to life.” (Gen 2:7). The LORD God forms the human (Hebrew ‘adam) out of “the fertile land” (Hebrew ‘adamah). Similarly, the LORD forms “all the wild animals and all the birds in the sky” out of the ground (Gen 2:19). The Hebrew term ‘adamah, means “soil” or “arable land:” ground you can till and plant (“fertile land,” as the CEB renders it). The very close similarity in sound between Adam, the human, and ‘adamah, the soil, is no accident: Hebrew loves puns! Adam is the mud man, formed from the ground. So while Genesis 1:1-2:4a begins with water, in Genesis 2:4b-25 the LORD forms the human and the animals from the ground.

This leads us directly into a third question to pose to these two passages: How does the Divine create? In Genesis 1:3, we read, “God said, ‘Let there be light.’”

Again in verse 6, we read, “God said, ‘Let there be a dome in the middle of the waters to separate the waters from each other.’” This pattern continues throughout the chapter (compare Gen 1:9, 11, 14, 20, 24). In this passage, clearly, God speaks the world into being.

But when we turn to Genesis 2:4b-25, we find a different way of thinking about the means by which the Lord creates. In Genesis 2:7, the Lord God formed the human from the ground.

Likewise in 2:19, “the LORD God formed from the fertile land all the wild animals and all the birds in the sky” The verb translated “formed” in the CEB is the Hebrew word yatsar: the term used for what a potter does (see Jeremiah 18:11).

In Genesis 2, the LORD is like a potter, forming the human, the animals, and the birds from the ground: getting the Divine hands dirty, and fashioning intimately and directly what the LORD creates.

The fourth and final question we will pose to these two passages is, What is the order of creation? The first thing that God makes in Genesis 1 is light (Gen 1:3-5). God calls light into being by pronouncing its name: God says, “Let there be light”—in Hebrew, yehi ‘or; that is, “Light, be!”—and light is.

Genesis 1:1—2:4a imagines creation as taking place over the span of a single week. Light is created on Day One, and everything else that comes into being is made over the course of six days. The last creative act of God, performed at the end of the sixth day, is the creation of human beings (Gen 1:26-31). In Genesis 1:1—2:4a, humanity is the climax of creation.

However, if Day Six marks the climax of creation, Day Seven is its culmination: the Sabbath, the day of rest, of worship, and of study. In Genesis 2:1-4a, even God rests on the Sabbath day! According to Genesis 1:1—2:4a, then, creation itself has a sabbatical logic. Sabbath is part of the structure of reality, woven into the warp and woof of the cosmos.

Now consider the sequence of creation imagined in Genesis 2:4b-25. Here, the first expressly described creative act of the LORD is the forming of the human. We are expressly told that this took place, “On the day the LORD God made earth and sky,” and “before any wild plants appeared on the earth, and before any field crops grew” (Gen 2:4b-5). In Genesis 2:5, then, we are expressly told that there were no plants when the human was created.

In Genesis 1, plants are created at the end of Day Three, while humans are created at the end of Day Six. But in Genesis 2, plants are created later, as the story unfolds, for the human: the LORD God plants a garden in Eden in order to provide food, a place of dwelling, and meaningful work (Gen 2:8-15).

Although the human seems to have in the garden everything required for life, something more after all is necessary: “Then the LORD God said, “It’s not good that the human is alone. I will make him a helper that is perfect for him [Hebrew ‘ezer kenegedo]” (Gen 2:18). The LORD at first sets out to make an ‘ezer kenegedo for the human, “a helper that is perfect for him,” by going back to the drawing board–or more accurately, to the mud pile! “So the LORD God formed from the fertile land all the wild animals and all the birds in the sky and brought them to the human to see what he would name them. The human gave each living being its name” (Gen 2:19). By giving the animals their names, the human completed their creation.

In Genesis 1, birds and fish are created on Day Five (Gen 1:20-23). The land animals, both the wild and domestic animals and the “crawling things” (the Hebrew remes refers to those things that either have too many legs or not enough: what we used to call “creepy crawlies” when I was a boy), are made on the morning of Day Six (Gen 1:24-25). Humans are made at the end of the sixth day, as the climax of creation. But in Genesis 2, the human is created before the animals. Indeed the animals, like the plants, are created for the human, in the quest to find an ‘ezer kenegedo.

But none of the animals can fill the role of ‘ezer kenegedo: “a helper that is perfect for him.” The human is still alone. Recognizing that more extreme action is called for,

the LORD God put the human into a deep and heavy sleep, and took one of his ribs and closed up the flesh over it. With the rib taken from the human, the LORD God fashioned a woman and brought her to the human being (Gen 2:21-22).

When he sees her, the delighted man says,

This one finally is bone from my bones

and flesh from my flesh.

She will be called a woman [Hebrew ‘ishah]

because from a man [Hebrew ‘ish] she was taken (Gen 2:23).

The creation of humanity brackets Genesis 2: God’s first creative act is to fashion the human (Hebrew ‘adam) from the ground, and God’s last creative act is to fashion the woman (Hebrew ‘ishah) from the man (Hebrew ‘ish).

When we listen closely and carefully to Genesis 1 and 2, it becomes evident that we really are looking not at one story of creation, but at two. One account, in Genesis 1:1-2:4a, imagines creation over the span of a single week. God speaks the world into being, and humanity is the climax of creation, the last thing made. In the second, in Genesis 2:4b-25, the LORD fashions the human, and fashions the animals and birds, forming them like a potter, from the soil. The human is the first thing that the LORD makes; everything else is made for the human. The creation of humanity, male and female, brackets the story: the man as the first creative act of the LORD God, the woman as the last.

If we try to collapse these two passages into a single account, the text resists us. One common attempt to harmonize the passages is to suggest that Genesis 2:4b-25 is a detailed expansion of the thumbnail description of Day Six from Genesis 1. But even setting aside the different ways of referring to the creator and the different ways of describing God’s creative activity in these chapters, the sequence does not work: Genesis 2 explicitly says that there were no plants when the human was made, and that the animals were made after the human. Collapsing the stories doesn’t solve our problems; it only creates different problems.

If we come to Genesis 1–2 seeking answers to our questions about how the world began, we will go away frustrated. Since there are two different, distinct, and separate accounts of creation in these chapters, they cannot both be factual depictions of how the world began. If I say, “I believe the Genesis creation account,” the next question must be, “Which creation: the first account, or the second?” But of course, we don’t have the leisure of choosing one or the other: there they both are, right at the front of our Bibles, presented to us in our canonical text of Genesis. The biblical text itself will not let us read Genesis 1–2 as a factual account of the beginning of the world.

Once we understand that Genesis 1:1—2:4a and 2:4b-25 are two different stories, however, we can consider how they relate to one another positively and creatively: not through some kind of artificial harmonization, but by seeing how these two accounts echo and resonate with one another.

William Carl, president of Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, is a gifted preacher and a trained musician who understands the value of dissonance, in music and in Scripture. When music is all consonance, Carl observes, it is boring, even irritating (think of the sugary bubble-gum pop songs that, in spite of yourself, stick in your head and drive you up the wall)! Good composers know that to create texture, you need discord to enrich and accentuate the harmonies. It is surely no accident that right at the very beginning of Scripture we find not only consonance, but also dissonance: two different ways of thinking about who God is; two different ways of thinking about our world and about who we are.

As long as I believe in an enchanted world, a world haunted by gods and demons in which every rock, stone or tree is possessed by a spirit, I can neither formulate laws to render the behavior of my world meaningful, nor make predictions based on those laws. The interaction of objects in the world will be due to the capricious decisions that those various spirits might make in their interactions with one another.

As long as I believe in an enchanted world, a world haunted by gods and demons in which every rock, stone or tree is possessed by a spirit, I can neither formulate laws to render the behavior of my world meaningful, nor make predictions based on those laws. The interaction of objects in the world will be due to the capricious decisions that those various spirits might make in their interactions with one another.