When our guys were small, a favorite television program was “Lamb Chop’s Play-Along,” which always ended with ventriloquist Sheri Lewis, joined by her puppets Lamb Chop, Charley Horse, and Hush Puppy plus a chorus of children, singing “The Song That Doesn’t End”:

This is the song that doesn’t end, yes it goes on and on, my friend. Some people started singin’ it, not knowin’ what it was, and they’ll continue singin’ it forever just because it is the song that doesn’t end. . .

Repeat as long as you can stand it–which I warn you for a toddler can be a LONG time!

Which brings us to the Psalm for this Sunday, Psalm 119:137-144. Psalm 119 feels like the Psalm that doesn’t end! This is the longest chapter in the Bible–indeed, at a whopping 176 verses, it is longer than many biblical books: by comparison, Jonah has only 48 verses, and Ephesians only 155. Those who have attempted to read through the entire psalm may also remember it as the dullest chapter in the Bible! There is no clear sense of development in the poem from beginning to end–indeed, as Carroll Stuhlmueller observed, “One can start at the end and read the verses backward, and it makes equally good sense”(“Psalms” in HarperCollins Bible Commentary, ed. James L. Mays [New York, NY: HarperCollins, 1988], 487).

However, this huge, sprawling text is also tightly structured. Psalm 119 is an acrostic poem. Unlike the acrostics with which we are familiar in English, where the first letters of successive lines spell out words or phrases, Hebrew acrostics use all twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet in order. Sometimes this is done in successive lines, as in Psalms 9—10; 25; 34; 111; 112; 145; and Proverbs 31:10-31. Sometimes, as in Psalm 119, successive sections or stanzas follow this alphabetical pattern (see also Ps 37; Lam 1; 2; 3; 4).

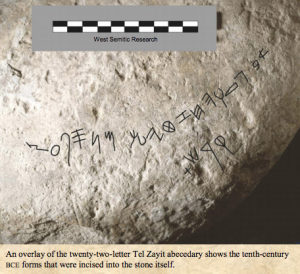

The biblical acrostics may vary a bit from our expected alphabetical order. The letters ‘ayin and pe switch places in Lam 2; 3; 4 and Ps 10–but that different sequence is also found in some ancient alphabet lists: for example, in the tenth-century BCE Tel Zayit Inscription discovered by my friend and colleague Ron Tappy (Ron Tappy, Marilyn Lundberg, P. Kyle McCarter, and Bruce Zuckerman, “An Abecedary of the Mid-Tenth Century b.c.e. from the Judaean Shephelah.” BASOR 344 [2006]:5-46). Sometimes, Hebrew poets play creatively with that order: for example, Psalm 34 skips waw and adds an additional pe at the end, so that while the twenty-two lines are preserved, the first, middle, and last letters of the acrostic spell out ‘aleph! But the point of the acrostic form remains completion. This is apparent even in the partial acrostic in Pss 9-10 (a single psalm in the LXX and the Latin Vulgate). While the middle of the alphabet is missing, the beginning and end are represented, making it most likely that the original poem was damaged or altered in the course of its editing and transmission–as the division of this poem into two psalms in the Hebrew Bible, reflected in our Old Testament, already may indicate.

In Psalm 119 the acrostic form is fully realized: the psalm consists of twenty-two stanzas, one for each letter of the Hebrew alphabet, each stanza consisting of eight verses beginning with that letter. In Hebrew, each line of Sunday’s Psalm reading begins with the letter tsade:

צ tsade

Lord, you are righteous,

and your rules are right.

The laws you commanded are righteous,

completely trustworthy.

Anger consumes me

because my enemies have forgotten what you’ve said.

Your word has been tried and tested;

your servant loves your word!

I’m insignificant and unpopular,

but I don’t forget your precepts.

Your righteousness lasts forever!

Your Instruction is true!

Stress and strain have caught up with me,

but your commandments are my joy!

Your laws are righteous forever.

Help me understand so I can live! (CEB)

Patrick Miller describes Psalm 119:137-144 as a hybrid poem, combining “Praise of God’s law and prayer for help against oppression” (see his note on this passage in the HarperCollins Study Bible [New York: Harper Collins, 1993], 832). Indeed, aspects of nearly every type of psalm can be found in Psalm 119, from hymn to thanksgiving to prayer for help. While some claim that mixing forms in this way showed a lack of fresh insight and creativity on the part of the Psalmist, James Luther Mays argued that the mixture of forms is part of the point the Psalmist wants to make. By deliberately drawing from and referring to a variety of sacred texts, the Psalmist aims to express “a more comprehensive knowledge of God” (James L. Mays, The Lord Reigns: A Theological Handbook to the Psalms [Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1994], 129). Psalms 1 and 19, which like Psalm 119 draw on several poetic forms, also resemble Psalm 119 in theme (compare Psalm 1:2 with Psalm 119:15; Psalm 19:7 with Psalm 119:129-130). All three psalms express a life of piety centered on torah: God’s law or instruction. In these psalms, Mays suggests, the book of Psalms is viewed not simply as a prayer book, but as instruction in the pious life (Mays, The Lord Reigns, 134-135).

The theme of Psalm 119 is expressed in the blessing pronounced in the first two verses:

Happy are those whose way is blameless,

who walk in the law of the LORD.

Happy are those who keep his decrees,

who seek him with their whole heart (NRSV)

The word translated “law” in Psalm 119:1 is, again, the Hebrew torah. Eight different legal terms are used in Psalm 119, ordinarily one to each verse. In addition to “law,” these terms in the NRSV are “decrees,” “statutes,” “commandments,” “ordinances,” “word,” “precepts,” and “promise.” Most of this legal vocabulary comes from Deuteronomy, where these words describe different aspects of God’s law. However, in Psalm 119 no attempt is made to define any of these technical terms, nor is any distinction made among them. Professor Mays suggests that in Psalm 119, they are all interchangeable with torah: they all represent instruction (Psalms [Interpretation; Louisville: John Knox, 1994], 382-383.)

Note, though, that this is the LORD’s instruction. Consistently, all these terms are identified as the property of the LORD: it is “the law of the LORD” (verse 1); “his decrees” (verse two); “your precepts” (verse four); “your statutes” (verse 5). Confirmation of this insight comes even in the apparent exceptions to the rule. In Psalm 119:3, none of the eight torah terms appear. However, the Psalmist speaks of the blessed as those “who do no wrong,/ but walk in his ways” (emphasis mine; see also Psalm 119:15 and 37). Similarly, Psalm 119:90 speaks of “your faithfulness,” evident in the establishment of the created world (see Psalm 19, which also places the LORD’s torah alongside the LORD’s creation as being alike changeless and reliable). Psalm 119:122 does not refer to the LORD’s instruction at all. However, this verse does identify the Psalmist as “your servant,” indicating again an attitude of obedience and submission consistent with the theme of this psalm.

Professor Mays writes,

The word of God is given but never possessed. Because it is God’s instruction, it is not owned apart from the teaching of God.… it must be sought and constantly studied in prayer in order to be taught ( Mays, Psalms, 385).

Psalm 119 does not identify God’s instruction with the written law: an important distinction, for the ideal of obedience to God’s will can all too easily be corrupted into petty legalism. Remember that Jesus’ opponents chastised him for breaking the law, while Jesus rebuked them for neglecting “the weightier matters of the law: justice and mercy and faith” (Matthew 23:23, NRSV). Unlike those among the religious leadership who opposed Jesus, the Psalmist recognizes that God’s instruction is also God’s gift, which cannot be possessed once for all but must be rediscovered in every time, by every seeker. In Christian theological terms, we are saved by grace!

Author Frederick Buechner expresses what this means very well:

A crucial eccentricity of the Christian faith is the assertion that people are saved by grace. There’s nothing you have to do. There’s nothing you have to do. There’s nothing you have to do.

The grace of God means something like: Here is your life. You might never have been, but you are because the party wouldn’t have been complete without you. Here is the world. Beautiful and terrible things will happen. Don’t be afraid. I am with you. Nothing can ever separate us. It’s for you I created the universe. I love you.

There’s only one catch. Like any other gift, the gift of grace can be yours only if you’ll reach out and take it.

Maybe being able to reach out and take it is a gift too (originally published in Wishful Thinking).

The poet who has given us Psalm 119 set for himself a very daunting task. Using a basic theological vocabulary of eight terms meaning “law” or “instruction,” the Psalmist set out to write twenty-two eight-line meditations on the place of God’s teaching in the life of the pious, committed believer–one meditation for each letter of the Hebrew alphabet. What is more, the Psalmist attempted to incorporate into this poem the various styles of the texts in which God’s instruction is encountered, including nearly every form of psalm. We may criticize the result as over-long and repetitive, but even so, Psalm 119 is a remarkable achievement.